CALGARY — The use of light technology is allowing archeologists to peel away the rainforest and reveal the remains of an ancient Mayan city nearly twice the size of Vancouver.

LIDAR, which stands for light detection and ranging, is a remote sensing method that uses light in the form of a pulsed laser. The light pulses and combines with other data recorded by the airborne system to generate precise, three-dimensional information about the shape of the Earth and its surface characteristics.

"It's just a game changer," said Kathryn Reese-Taylor, a professor in the department of anthropology and archeology at the University of Calgary, said in an interview with The Canadian Press.

"You can be trying to survey and to map sites in the rainforest, and what would take you years to accomplish, LIDAR can do in a couple of days of flying over these large areas."

Reese-Taylor has been working for years with the Bajo Laberinto Archaeological Project, a University of Calgary-led multidisciplinary research project, in conjunction with Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH) Campeche in Mexico.

She and a colleague first visited the ancient Calakmul settlement over a decade ago.

"We hiked 13 kilometres to get there, looked around, oohed and aahed at all of the enormous unexcavated and unlooted ruins at the site, and then walked back," Reese-Taylor.

"Being on the ground and climbing these structures and looking at the landscape all around it — it's just an incredible experience. Some of these structures you may be the first person to walk on in over a thousand years, so it's really exciting."

She saidthe site of Calakmul was the new capital of the powerful Kanu’l (Snake) dynasty, which dominated geopolitics of the Mayan Lowlands, controlling a vast network of vassal kingdoms.

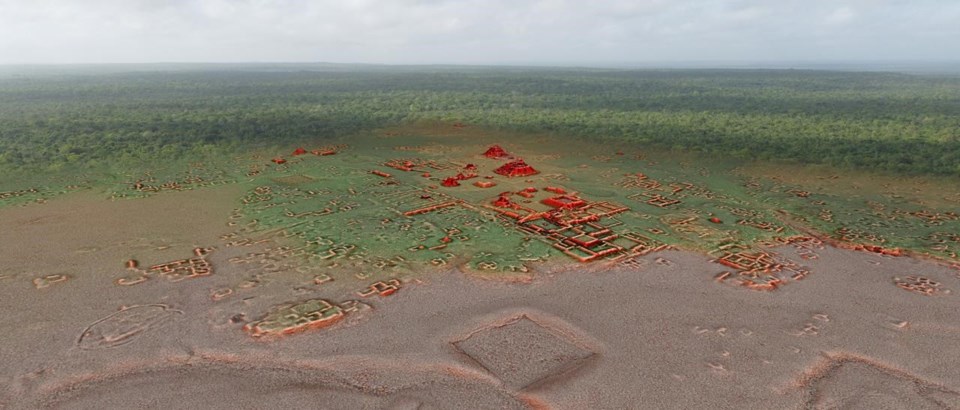

The results of the LIDAR scan give a better idea of the urban settlement and landscape modifications in the capital city itself, Reese-Taylor said.

"What other people might just think is a big hill, we know under it is a huge temple, for instance, or a palace. So we can see all of that.

"Apartment-style residential compounds have been identified throughout the surveyed area, some with as many as 60 individual structures. These large residential units were clustered around numerous temples, shrines and possible marketplaces, making Calakmul one of the largest cities in the Americas at 700 AD."

Reese-Taylor said researchers are able to see that the magnitude of landscape modification equalled the scale of the urban population. All available land was covered with water canals, terraces, walls and dams.

"It peels away all the vegetation and we can see exactly what we're looking for. And every time we get LIDAR, it's like opening up one of your favourite Christmas presents that you just don't know what to expect.

"I's an incredible gift when your get to pore through it and see what's actually there."

Reese-Taylor said she will be heading to the site in April, once her classes at the University of Calgary are done, and intends to spend two months at the site before the annual rainy season begins.

She said the site so far encapsulates 195 square kilometres, and that's huge.

"One of the biggest cities in the Americas at this time," she said. "Almost two Vancouver's could have gone into this area. Washington, D.C., is about the same size, as well as Amsterdam and Brussels."

Reese-Taylor said although the presence of temples and palaces is tempting, the initial excavation will be a little more mundane.

"I do want to dig in the new temple really badly. But I think right now we've got to focus on the households — just because we have some information on the history of the temples and the downtown civic structure, but we have no data on the people who actually lived there."

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Oct. 29, 2022.

Bill Graveland, The Canadian Press