SANTA FE, N.M (AP) — A coalition of human rights groups on Tuesday leveled new criticism at a privately operated migrant detention facility in New Mexico where they say fast-track asylum screenings routinely take place without legal counsel or adequate privacy during sensitive testimony.

The rights groups say the broken screening system at the Torrance County Detention Facility means that migrants with strong, viable claims to asylum — who can’t go back to their country because of persecution or the threat of torture — are instead being screened out inappropriately for deportation as the Biden administration seeks to impose severe limitations on migrants hoping for asylum at the border.

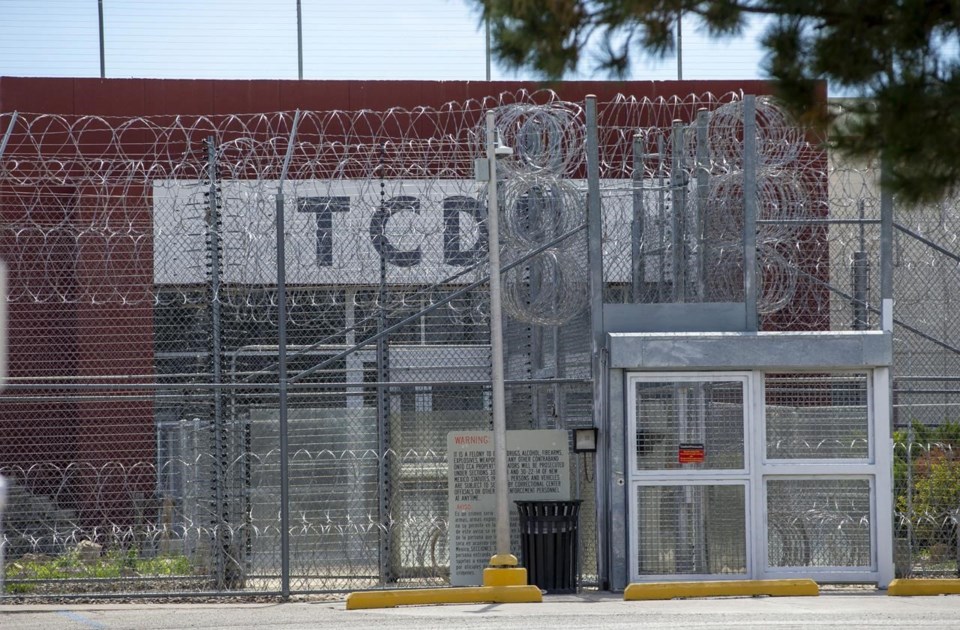

The 187-page complaint and findings were made by the American Civil Liberties Union and three advocacy groups that provide legal services to asylum-seekers. They're urging the U.S. government to end its contract with the private company that runs the facility, which is overseen by Immigration and Customs Enforcement. The report also catalogued complaints of retaliation against migrants who raise objections to asylum procedures and living conditions.

The report arrives roughly a year after Brazilian migrant Kesley Vial killed himself during detention at the Torrance County facility. The 23-year-old was scheduled for removal when he took his own life.

Most initial interviews at the facility are being conducted without access to a crucial legal orientation, and other key legal requirements are routinely ignored, the groups say. As migrants appeal their initial rejection to an immigration judge, many are denied access to files in their own cases, leaving them to challenge “secret decisions they have never seen,” according to the report.

The Torrance County facility was repurposed in January to conduct expedited asylum screenings as immigration officials started to unwind coronavirus restrictions on asylum that allowed the U.S. to quickly turn back migrants, the report says. The complaint outlines how ICE has fast-tracked hundreds of asylum screenings at the facility in Estancia, about 250 miles (400 kilometers) north of the U.S. border with Mexico.

Advocacy groups estimate about 30% of detainees at the facility have passed asylum screenings since December 2022, far below the national average of 73% for the December-July period. That national average slid to 56% in the July 16-31 period.

Separately, the Biden administration launched speedy asylum screenings in April at Border Patrol holding facilities along the Southwest U.S. border, where the promise of attorney access appears largely unfulfilled.

Those who pass initial asylum screenings — to determine whether there is a “credible fear” of persecution or torture — are generally freed into the U.S. to pursue their asylum cases in court. Those who fail are supposed to be deported.

“The credible fear process at Torrance County Detention Facility is particularly flawed, pass rates are unusually low and many individuals detained … are deprived of due process,” says the report, signed by the New Mexico Immigration Law Center, Las Americas Immigrant Advocacy Center and Innovation Law Lab.

The administrative complaint was filed directly to U.S. immigration authorities at the Department of Homeland Security, urging the agency to terminate the contract at Torrance County with private detention company CoreCivic.

Media representatives for Homeland Security had no immediate response to the report. CoreCivic spokesman Brian Todd characterized it as inaccurate and misleading.

“We are firmly committed to providing those in our care with access to counsel and access to courts,” he said in an email.

It’s unclear whether screening arrangements by ICE at Torrance County are replicated elsewhere — the advocacy groups didn’t survey facilities in other states for the purposes of the complaint.

The report also describes situations where initial screening interviews by telephone with asylum officers are easily overheard by other migrants, citing testimonials from migrants who express alarm at the lack of privacy and fear of recounting past persecution abroad, including conflicts with organized crime and sexual assault. Those initial interviews with asylum officers take place in cubicles separated by thin partitions that don’t reach the ceiling and white-noise machines that reportedly don’t do enough to drown out conversations.

Alberto Mendez, a 33-year-old Salvadoran national, said his asylum screening at the Torrance County Detention Facility took place in unison with 15 other migrants, without prior legal advice, and ended in rejection.

“The cubicles don’t have a roof, they just have dividers. So we all hear what everyone is saying. Everything,” said Mendez, a father of three who worked as a cook and Uber driver on the outskirts of San Salvador until he fled threats and relentless recruitment campaigns by gangs.

“My fear was that what you were saying would be divulged in your own country,” he said. “And that could bring reprisals and even bigger consequences.”

Aside from the procedural issues, a federal watchdog in early 2022 detailed unsafe and unsanitary conditions at the Torrance County facility during an unannounced inspection — recommending that everyone be transferred elsewhere. Those findings from the Department of Homeland Security Inspector General were disputed by CoreCivic and ICE officials.

CoreCivic has said the detention center is monitored closely by ICE and is required to undergo regular reviews and audits to ensure an appropriate standard of living for all detainees and adherence agency’s strict standards and policies.

Support for the facility among elected officials has wavered. On Friday, Democratic U.S. Sen. Martin Heinrich of New Mexico renewed calls for ICE to terminate its contract with CoreCivic at Torrance County, in a letter also signed by Sen. Ben Ray Luján and Congresswoman Melanie Stansbury.

A panel of state legislators met Tuesday to revisit a failed bill to restriction immigrant detention in New Mexico. The state Senate in March voted down the initiative, which would've prohibited local government agencies from contracting with ICE to detain migrants as they seek asylum.

States including California, Illinois and New Jersey have enacted legislation in recent years aimed at reining in migrant detention centers in their territory.

Morgan Lee, The Associated Press