BALZAC - About a 10 minutes drive south of Airdrie just west of Highway 2 between Balzac and the northern boundary of Calgary is a uniquely important archaeological site that documents Indigenous subsistence and cultural activities spanning a time period of 2,000 years.

The Balzac Archaeological Site was first rediscovered in the late 1970s. It was one of the early beneficiaries of historic resources legislation passed in Alberta in 1973, which began requiring companies to undertake historic resource assessments prior to construction.

“Up until that time, most sites in the province went unnoticed, other than a little research that was being done by the Glenbow Institute and then the University of Calgary,” explained Brian Vivian, a senior archaeologist and partner with Lifeways Canada. “The Balzac Site was first discovered when they were doing an assessment on a then pipeline that was going past that location.”

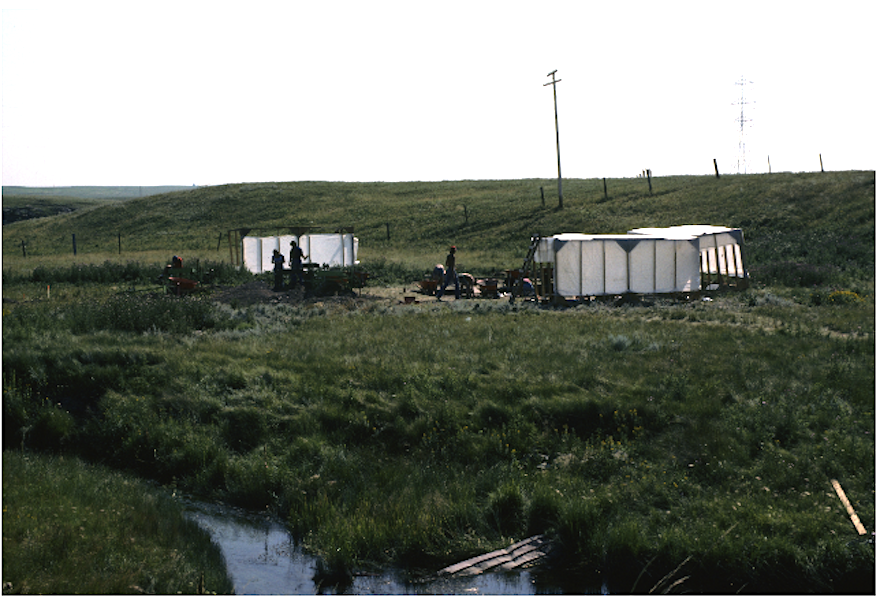

The first credited archaeological work undertaken at the site was done by Stan Van Dyke, but the site was given its first rigourous excavation in the early 1980s by archaeologists Thomas Head and later Bea Loveseth. That’s when Vivian enters the story.

As a newly graduated archaeologist with a degree from Vancouver's Simon Fraser University in his pocket, Vivian was offered his first archeology job by Lifeways Canada in 1981. That first job was working as a crew member on Bea Loveseth’s team, which was exploring the Balzac Archaeological Site.

More than four decades later, Vivian still recalls his work at the site fondly, saying it was an almost “textbook” example of what an archaeological site was supposed to be.

“It was amazing,” he said. “It was my first opportunity to work on a site in Alberta and it was one of the first archaeological sites I had worked on. That was what you expected archaeology to be – the excavation of a site with features and things like that.

“I have a career going on to 40-plus years, and I have worked at some amazing sites. But the Balzac site, especially for Calgary, the Nose Creek Valley and Airdrie, is a really important site. And it is recognized as being one of the most important sites in that area.”

What makes it so special, explained Vivian, is the clearly stratified layers of Indigenous occupation of the site stemming back at least 1,800 years to what is known as Late Prehistoric. Because it was in a river valley, Indigenous peoples would come and use the site to process their bison kills, and the sediment from what is now known as Nose Creek would rise up and bury the site, preserving the archeology perfectly.

This process happened over and over again, said Vivian, leaving a clear demarcation between periods of occupation with cultural artifacts and animal bones, mainly bison, preserved in each layer.

The earliest occupation levels of the site have been reliably dated to the Avonlea period – a time when Indigenous peoples, who, still without horses, were adopting their first bow-and-arrow technology. They began stalking and hunting bison out on to the open prairie instead of just relying on buffalo jumps and buffalo pounds, as they had for many years up to that point.

“A lot of the bison kills found at that time were more the classic jumps or pounds (at the start of the Avonlea period),” Vivian confirmed. “In the Calgary area, we have all sorts of pounds found over toward Medicine Hill, or what used to be called the Paskapoo Slopes (where Canada Olympic Park is located). But in the Avonlea period (bison hunting) seemed to shift out into the open prairie a little bit more. In that way, the Balzac Site is exemplary of bison kills happening out in the open prairie area.”

But the extraordinary human story of the 10-hectare Balzac Archaeological Site hardly ends there, according to Vivian.

“At the latest occupations of the site, there were actually metal (arrow) points found there – so there would be people coming and staying at that location right up until the fur trade era, where you have the introduction of European trade goods,” he explained.

“So, basically, for 1,500 years people are coming back to that site again and again, and in the stratification you can separate out all those periods of time. You can start comparing what was happening at one period of time with 100 years earlier.”

As to why the Balzac site was such a popular spot for Indigenous people to stop to process their kills over such a long period of time remains a bit of a mystery, Vivian admitted. But he added local geography likely had something to do with it, considering the accessibility of water and a good pound or kill zone just north of the site.

What was done at the site was not hunting, he explained, but rather animal butchering and food processing.

According to the Alberta Register of Historic Places, over 7,000 artifacts have been recovered from the site to date and 120,000 preserved bones from all eras represented at the site.

“It would be lots of butchered bone and associated tools, and things of that sort,” Vivian further explained. “There are lots of ceramics also recovered from the Balzac site. One of the things that is really quite amazing about it is it is a kill processing site; so there are a lot of features – basically cooking hearth features and things like that.

“It is a location where people have been hunting bison, but the bone beds for the hunt might possibly be upstream or into the valley and some of the bones got washed away … What we are left with is the remnant of the processing area.”

Vivian also feels it is likely not a coincidence that the Balzac site is located so near a major modern thoroughfare like Highway 2.

“What people forget is Highway 2 follows the old Edmonton Trail, and the old Edmonton Trail was probably long established before it even became a highway, or a railway, or a stagecoach road,” he said. “It was probably an Aboriginal route; so that’s another regional reason why that site is probably located along that same location. It is in proximity to an Aboriginal trail that has probably been there for thousands of years.”

What the Balzac site teaches us, according to Vivian, is time keeps moving on, and each successive generation leaves its footprint and its artifacts behind. He said what still shocks him a bit is his first memories driving out to the Balzac site’s location as a young archaeologist back in 1981, compared to how easy it is to drive past relatively closely to it today.

“When I first worked there, Calgary only went so far as Beddington Creek, which is now properly known as West Nose Creek,” he confirmed. “I remember on the drive out, we were taking a back road going out past this big erratic (boulder) and then onto a section road where you turn and go out toward the site.

“Now all of that is built out – in the 40 years, all of that has become city. It’s not going to be very long before (the Balzac site) is right within the edge of what is Calgary.”

Vivian said he does not worry about the Balzac Archaeological Site’s future preservation despite these development pressures, as the site is well-known, well-mapped, and well-protected by heritage legislation thanks to the thorough work done by archaeologists at the site in the early 1980s and beyond.

“I think we are lucky that the steps were taken to protect that site 40 years ago, recognizing how important it was to protect it,” he said.

It is illegal to disturb or take artifacts from a registered archaeological site. Furthermore, the Balzac Archaeological Site is also located on private land; so permission is required before coming near the site.

The best way to find out more about it and other archaeological sites in the Calgary region is to read the City of Calgary’s brochure on the subject at archaeology-and-calgary-parks.pdf.