More than eight in 10 urban residents live with unsafe levels of particulate pollution, a new study suggests, including those in the Edmonton region.

George Washington University environmental health professor Susan Anenberg co-authored a study on the effects of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) on health in cities Jan. 5 in The Lancet Planetary Health.

PM2.5 is a pollutant that consists of particles 2.5 micrometres or smaller, many of which form in the air as they react with other pollutants, said St. Albert air quality consultant David Spink. These particles are small enough to penetrate deep into the lungs and bloodstream, where they can cause various lung and heart diseases and premature death.

Air pollution is one of the top five factors influencing global human health and is comparable to high blood pressure and tobacco use, Anenberg said.

“This is a very substantial public-health problem that needs to be central on the public-health agenda,” Anenberg said.

While many studies have confirmed pollution’s negative effects, Anenberg said none had looked specifically at how it affected human mortality in cities.

The study

Anenberg and her team used data from ground monitors, satellites, computer models, and the Global Burden of Disease Study to calculate how PM2.5 levels affected death rates in 13,160 cities, including Edmonton, between 2000 and 2019.

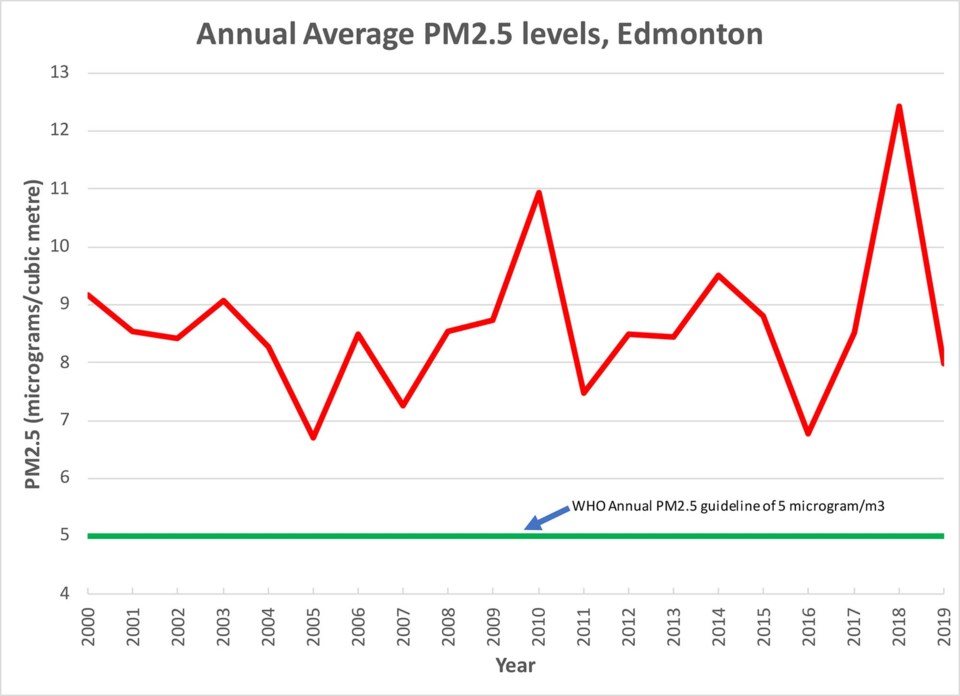

The team found that annual PM2.5 levels in the world’s cities averaged 35 micrograms per cubic metre in 2019, or three times the World Health Organization’s 2005 guideline of 10 micrograms. (The WHO’s guidelines indicate the level beyond which you definitely see health impacts, Spink explained. The WHO lowered its PM2.5 guideline to five micrograms in 2021.)

The team estimated that about 85 per cent of urban residents — some 2.5 billion people — live in areas that exceeded the WHO’s 2005 guideline for PM2.5 in 2019. This led to some 1.8 million excess deaths, 140 of which were in Edmonton.

The study found that cutting PM2.5 pollution did not always reduce pollution-related deaths. This is because demographic factors, such as an aging population and poor general health, can sometimes swamp out the benefits of cleaner air. China and the Western Pacific saw more deaths despite pollution cuts from 2000 to 2019 because their population grew larger and older, resulting in a larger group of vulnerable people, Anenberg explained. Europe’s population shrank along with its pollution rates, in contrast, and did see a drop in death rates.

Clearing the air

Spink said St. Albert’s recent cold snap likely worsened the region’s PM2.5 exposure by trapping pollution through temperature inversions (where warm air high up traps cold air near the ground).

“We’re really fumigating ourselves with automobile exhaust during periods like we have now,” he said, speaking on Jan. 5 when it was -31 C.

Spink said St. Albert’s main source of air pollution is transportation. While working from home can help, he said St. Albert and the province should build charging stations and offer rebates to speed the shift to zero-emission electric vehicles. He also called for stronger rules against tampering with vehicle emission controls, which drivers often remove to improve mileage.

Anenberg said governments should align their air-pollution standards with those of the WHO to ensure they protect public health. (Canada’s annual PM2.5 standard is 8.8 micrograms per cubic metre as of 2021; the WHO’s is five micrograms.) More walkable neighborhoods would also reduce air pollution.

Anenberg said her team is now studying the health effects of ozone (a common ingredient in smog) and working to help cities see the benefits of air-pollution action.

“They can actually reduce their air-pollution contribution and slow down climate change at the same time by reducing fuel combustion.”

Readers can explore the study’s data at bit.ly/3tmsXvB and read the study itself at bit.ly/3f1rm5L.