CANMORE – Alberta Transportation is formally asking for construction bids on the long-awaited wildlife overpass on a deadly stretch of the Trans-Canada Highway east of Canmore.

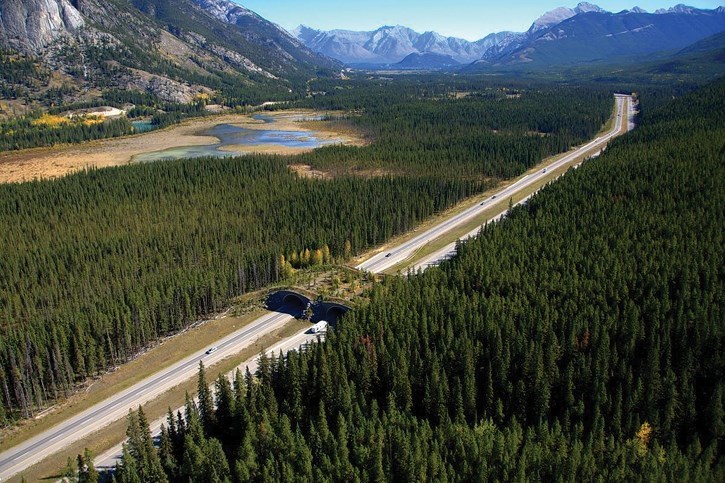

The steel arch wildlife overpass to be built at a collision hotspot near Bow Valley Gap east of Lac Des Arcs – the first of its kind in Alberta outside of Banff National Park – was put out to public tender on Nov. 2.

The Yellowstone to Yukon (Y2Y) Conservation Initiative was delighted to hear the news, particularly in light of a growing body of evidence around the world showing crossing structures and associated fencing help prevent car crashes and save the lives of people and wildlife.

“We’re excited. It’s a really significant step forward for mitigating the impacts of highways on wildlife in Alberta,” said Adam Linnard, Y2Y’s Alberta program manager.

“Different animals need different kinds of crossing structures in different locations depending on their needs, and this is obviously a huge step towards making that a greater possibility.”

Alberta Transportation completed a detailed design of the wildlife overpass in 2020 and put the project on the capital books for 2020-21. It is part of a $15 million spend over three years to identify problem areas for vehicle-wildlife collisions.

“The tender closes December 2, with construction expected to begin in spring 2022,” said Rob Williams, press secretary to Alberta Transportation Minister Rajan Sawhney in an email. “The project will take three years to complete.”

The Bow Valley is considered one of the four most important east-west wildlife connectors in the entire 3,200-kilometre length of the Y2Y region and one of two important connectors for wildlife in Alberta.

Deer, elk, bighorn sheep, moose, cougars, lynx, wolves, black bears and grizzly bears use the high quality habitat along the Bow River valley bottom to move between the protected areas of Banff National Park and Kananaskis Country.

In addition to being a critical wildlife link in the Y2Y region, the Bow Valley is also a busy thoroughfare for people.

Linnard said a staggering 30,000 vehicles buzz through the valley on the Trans-Canada Highway every day throughout summer – and that equates to approximately one car every two-and-a-half seconds.

“We know that grizzlies are known to treat roads as impassible when there’s as few as 100 cars a day on a road,” said Linnard.

“We know that grizzly bears that are travelling up the Kananaskis River, for example, are likely to encounter that road and simply not continue down the Bow Valley,” he added.

“That’s a big problem for their connectivity, a big problem for them finding food and water and mates, and establishing genetic diversity here.”

A 2012 study by Miistakis Institute and Western Transportation Institute identified 10 sites along a 39-kilometre stretch of the Trans-Canada Highway from the east gate of Banff National Park to Highway 40, recommending fencing and associated underpasses.

The study also called for one overpass at Bow Valley Gap east of Lac Des Arcs. That section of highway has historically seen the highest number of wildlife-vehicle collisions in the entire study area.

Banff-based scientist Tony Clevenger, who headed up the 2012 study and led Banff National Park's wildlife crossing research for almost two decades, said it’s great news to hear the long-awaited wildlife overpass will be built.

“The wildlife overpass is one of several locations that we have identified where collision risks with wildlife are high, in addition to connectivity needs,” he said.

“This is an important first step for Alberta Transportation as it starts utilizing roadkill and wildlife movement corridor data to inform where their investments are needed most in the province.”

Clevenger also headed up Banff National Park’s research on its wildlife crossing structures for many years.

In Banff National Park, there are 38 wildlife underpasses and six overpasses along an 82-kilometre stretch of highway from the national park’s east entrance to the border of Yoho National Park – the most wildlife crossing structures and highway fencing in a single location on the planet.

The wildlife exclusion fencing that parallels the highway throughout the park has reduced wildlife-vehicle collisions by more than 80 per cent and, for elk and deer alone, by more than 96 per cent.

Tracking animal movement at the wildlife crossings was made a top priority by Parks Canada from the get-go, which led Clevenger and his team to discover that there is a learning curve for animals to begin using wildlife crossings after construction.

For wary animals like grizzly bears and wolves, it may take up to five years before they feel secure using newly built crossings. Elk were the first large species to use the Banff crossings.

Research in Banff has shown that grizzly bears, elk, moose and deer prefer wildlife crossings that are high, wide and short in length, including overpasses. Black bears and cougars seem to prefer long, low and narrow crossings.

With all this in mind, Clevenger, a wildlife biologist, said it’s vital that Alberta Transportation put money and resources into monitoring the wildlife overpass near Lac Des Arcs once it is completed.

“The Trans-Canada Highway continues to be a deadly highway corridor for wildlife and traffic volumes are only going to increase over time,” he said.

“It will be important that Alberta Transportation allocates funding to monitor the overpass to evaluate how well it functions at moving wildlife and reducing roadkills in the area.”

Associated with the new overpass will be about 12.5-kilometres of wildlife fencing along the highway stretching to Dead Man’s Flats. There will also be jump-outs in the fencing so wildlife that get stuck on the highway can get back to safety on the other side of the fence.

The existing Dead Man’s Flats underpass was funded by the G8 Legacy Project and the Stewart Creek underpass was a joint venture between Three Sisters Mountain Village and Alberta Transportation.

“The Dead Man’s Flats underpass has significantly reduced collision rates and has paid for itself in less than 10 years, according to our cost-benefit analysis,” said Clevenger.

Construction of a wildlife overpass marks an institutional change in how Alberta Transportation goes about doing business, said Clevenger, by incorporating ecological needs in the highway corridor in addition to motorist safety and mobility.

“This is long overdue but welcome,” he said.

Linnard said wildlife connectivity is what keeps wildlife populations healthy, robust and resilient in the face of change, including climate change, and animals need to be able to move throughout their range as they have always done.

He said the Bow Valley is one of the few east-west valleys through the Rockies that is wide and flat and relatively low elevation – but it’s heavily compromised by a lot of human activity and development.

“Highway mitigations are really exciting because they’re one of the things that we can do that really makes things better for wildlife,” said Linnard.

“Often, what we’re doing is trying to keep things from getting worse, and this is one of those cases where we can actually make things better,” he added.

“If wildlife can keep moving through the Bow Valley, they can keep their genetic diversity, they can keep resilient, and then they have a better chance of surviving in the face of change.”

Linnard said he hopes with construction of a new overpass on provincial lands in the Bow Valley that momentum will be carried forward for other areas where wildlife face pressures, including in the Crowsnest Pass in southern Alberta.

“Certainly the Crowsnest Pass is the next obvious place,” he said, noting there is currently a long-term plan for a wildlife underpass on Highway 3.