YOHO/KOOTENAY – The Burgess Shale fossil beds in the Canadian Rocky Mountains continue to provide scientists with clues into the development of early life at the bottom of a prehistoric ocean 508 million years ago.

The most recent discovery of a new species of marine animal, Gyaltsenglossus senis, has provided researchers with evidence in the historical debate among zoologists over how the anatomies of the two main types of hemichordates are related.

Hemichordates, explained Dr. Karma Nanglu, are marine invertebrate animals, and two species – enteropneusta and pterobranchia – have long puzzled biologists as to their early evolution and how they are related as the two species appear quite different, but are closely related genetically.

Nanglu recently co-authored a paper with Dr. Jean-Bernard Caron of the Royal Ontario Museum and Christopher B. Cameron that revealed the new species and its role in solving the mystery of how enteropneusta and pterobranchia are connected.

Both researchers came across fossils collected at the Marble Canyon fossil bed site in 2010 and recognized it could be significant. Caron made notes about their possible significance at the time the 33 specimens were collected in the field from a continuous unit of rock in the fossil bed.

"I was going through the collection when I saw them for the first time ... I was completely unaware of their existence until I came across them in 2017," Nanglu said.

"[Caron] had made the exact same notes four to five years before I was working on my PhD. It worked out really well, we both independently came to the conclusion and we both had a great deal of confidence going into the project."

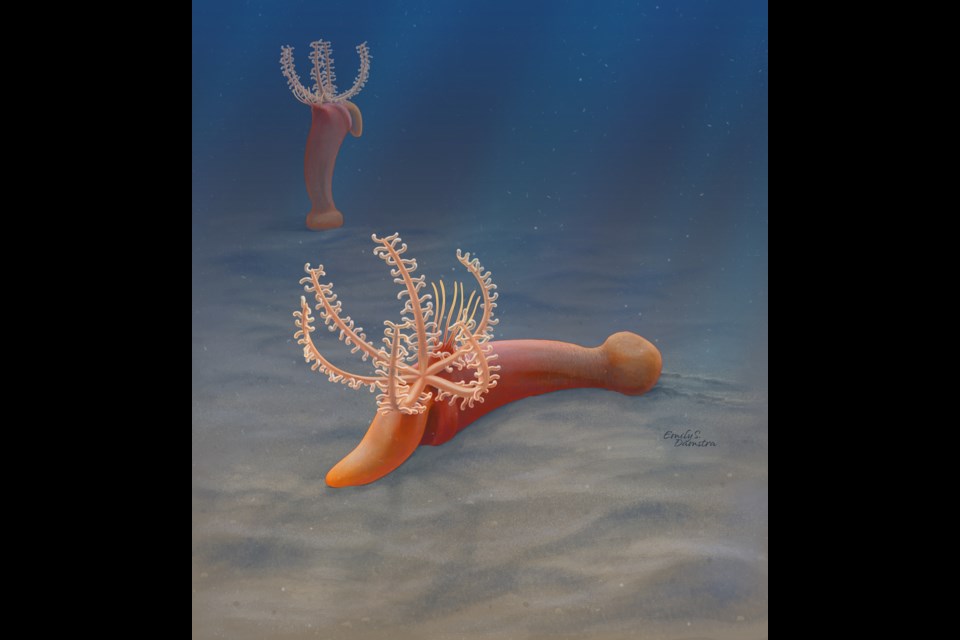

Enteropneusta are more commonly known as acorn worms. They are long, mud-burrowing animals found in oceans around the world. Pterobranchs are microscopic animals that live in colonies. Each is protected by tubes they construct and that feed on plankton using a crown of tentacled arms.

Nanglu said the two species look very different, but DNA tells us they are related, so understanding the origins of their evolutionary relationship has been a question posed by zoologists.

Because hemichordates are soft-bodied animals, finding evidence of them in fossils has been extremely difficult. Nanglu said there are only a handful of exceptionally preserved fossil species that illustrate their half-billion-year long history.

"Tyring to come up with morphological or anatomical evidence that connects the two of them has been difficult," he said.

The Gyaltsenglossus specimens collected are two centimetres in length and are remarkably preserved in terms of the soft tissue, providing detailed anatomical structures. The fossils show characteristics of both acorn worms and pterobranchs.

The fossils have an oval-shaped proboscis of the acorn worm and the basket of feeding tentacles similar to pterobranchs. Its age and the and combination of attributes from both hemichordate species makes it an important discovery.

Nanglu said it suggest this ancient species was able to use feeding strategies from both modern species of hemichordates – the tube that feeds on the nutrient-filled mud and the feeding arms that grab food suspended in the water.

Human evolution can be traced back through to hemichordates like the Gyaltsenglossus, which are part of the division of animal life called deuterostomia. Nanglu said by looking at this newly identified fossil, we are actually looking at a very distant relative of our own branch of vertebrates.

"Broadly speaking, these fossils occur quite early in the history of complex microscopic life," Nanglu said. "They are important for that reason – they occur very close ot the evolutionary origin of many groups."

The discovery and paper – Cambrian Tentaculate Worms and the Origin of the Hemichordate Body Plan – was published in the scientific journal Current Biology at the end of August.

It is the nature of the Burgess Shale fossils that provide excellent preservation of fine details of soft bodied deep-water creatures that allowed Nanglu and researchers at the Royal Ontario Museums to make the discovery.

Mudslides on the bottom of the ancient ocean that used to cover the Rocky Mountains 500 million years ago trapped soft-bodied creatures like the Gyaltsenglossus in material that preserved them as they fossilized over time. This feature of the Burgess Shale is why it was declared a UNESCO world heritage site in 1980 due to the quality and nature of the natural history found in the fossil beds.

"The Burgess Shale has been pivotal in understanding early animal evolution since its discovery over 100 years ago," said Caron in a press release. "In most localities, you would be lucky to have the hardest parts of animals, like bones and teeth, preserved, but at the Burgess Shale even the softest body parts can be fossilized in exquisite detail.

"This new species underscores the importance of making new fossil discoveries to shine a light on the most stubborn evolutionary mysteries."

The Mount Stephen fossil site was found in 1886 by railway workers, while Charles Doolittle Walcott discovered Walcott Quarry in 1909 while on expedition for the Smithsonian.

In February 2014, Caron announced the discovery of the Marble Canyon site in Kootenay National Park.

Nanglu currently holds the Peter Buck Deep Time post-doctoral fellowship at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.

He was able to look at Walcott's original collection to see if any Gyaltsenglossus fossils were discovered from the other site. They also looked at Mount Stephen fossils to see if they could find the species.

He said they have so far only been found a the Marble Canyon site. It has yielded an ever-growing list of new species that provide a glimpse of what life looked like on the ocean floor 508 billion years ago.

"What I found was really interesting was trying to imagine the whole quarry of animals we are finding, which are 500 million to 600 million years old," Nanglu said.

"The soft tissue is really the name of the game. Without that information we are stuck with a tiny fraction of the total information we need in order to reconstruct evolutionary relationships and understand the early origins of the planet.

"The Burgess Shale is one of the best examples of that kind of exceptional preservation."

The Walcott Quarry and Mount Stephen sites are only accessible to the public during a guided hike with Parks Canada or the Burgess Shale Geoscience Foundation. The Stanley Glacier site is also a guided hike with Parks.

Senior land use specialist for Lake Louise, Yoho and Kootenay Todd Keith said tours resumed mid-August after the COVID-19 pandemic led Parks Canada to close national parks in March with a limit of six hikers per tour.

"Parks Canada initially closed the national parks to visitation at the start of the COVID pandemic and we have been gradually taking a phased approach to resuming operations in the mountain parks," Keith said. "Given the COVID situation we are taking guided hikes with reduced numbers of visitors."

Protocols include keeping hikers within cohorts, regular use of hand sanitizer and not sharing fossil specimens between cohorts on the tour.

The ROM was considering conducting field work at the Marble Canyon site this summer, however due to the pandemic plans were called off.

"They had initially intended to come for a research trip this summer in 2020, but near the beginning of the pandemic they decided it was best to postpone," Keith said. "They have indicated they would like to come back in 2021 if the COVID situation makes that feasible."

For Keith, supporting the continued research into evolution of early multi-cellular life fits well into the reason why Parks Canada exists.

"One of the important purposes of protected areas like the national parks is to support scientific research into the natural sciences," he said. "This kind of research is really interesting and Parks Canada is proud to play a role protecting these sites so the researchers can continue to explore them and discover these new species and new understanding of how life first evolved from the early Cambrian period."