ALBERTA – A team of researchers has found a link between horn size and reproductive fitness in female Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep, highlighting a potential conservation issue where male trophy hunting is concerned.

A study led by University of Alberta PhD candidate Samuel Deakin points to trophy hunters selectively eliminating males with larger horns having a trickle-down effect on females of the species, possibly slowing population growth.

“Obviously, with males, the ones with bigger horns are more likely to win male fights and then get access to the females to reproduce,” said Deakin. “But no one’s really looked at the females and how horn size affects their reproductive success.”

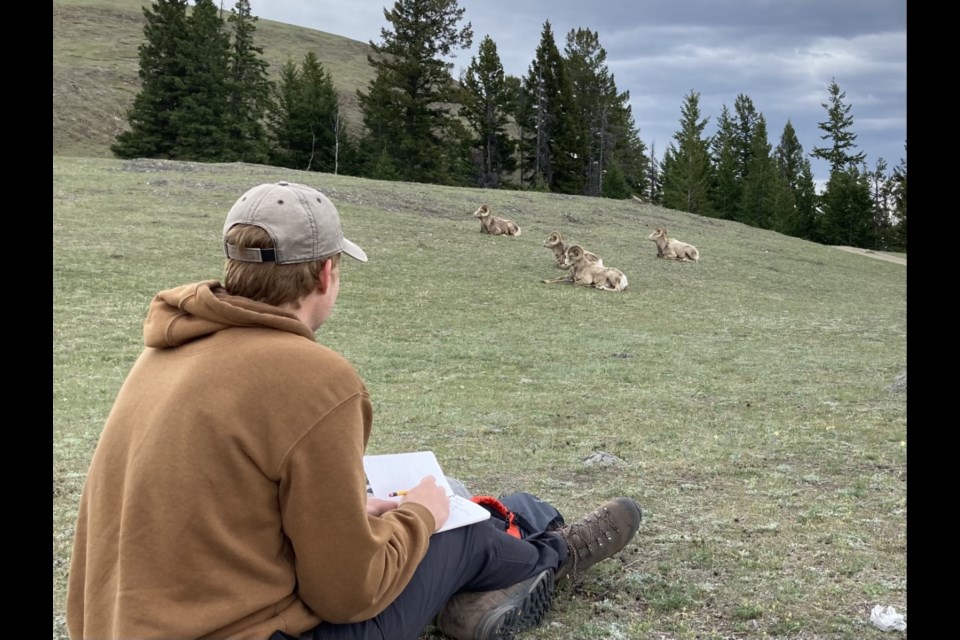

Researchers examined 45 years’ worth of data on a population of bighorn sheep in Ram Mountain, a remote area about 30 kilometres east of the Rocky Mountains near Nordegg, Alta.

It was possible to measure reproductive fitness in this population by taking into account not only horn size, but also the number of offspring each female gave birth to and the quality of the offspring.

Long-horned females were found to usually have their first lamb by the age of three, the study found, while short-horned females had their first lamb by the age of five.

While Deakin said the horns themselves aren’t directly affecting female reproductive fitness – there is no evidence to support the use of horns by females for competition, like males – there could be a potential gene association with horn size that influences reproductivity in ewes.

Past research has shown that ewes with larger body mass tend to be more successful mates, birthing lambs at an earlier age and weaning them earlier as a result.

The study found that variation in age at primiparity – the age when a female bighorn sheep bears a lamb for the first time or has given birth to an offspring at one time – and age at first offspring weaned was associated with both horn length and body mass when controlling for environmental factors.

“Both female mass and environment factors were associated with age at primiparity and age at first offspring weaned,” the study states. “However, horn size appeared to explain more variation than body mass in age at first offspring weaned, and to be the most explanatory variable of variation in lifetime reproductive success.

“Thus, larger horns correlate with higher reproductive fitness in both male and female bighorn sheep.”

Males have a clear purpose for secondary sexual traits such as horns or antlers. However, the purpose of secondary sexual traits like horns or antlers is less clear for females.

The relationship between horn length and female reproductive fitness may result from shared genetic architecture, the study explains, if genes for greater fitness are associated with genes for larger headgear.

“This suggests trophy hunting and selective harvesting of males based on horn size couple deplete the inheritance of traits associated with greater female reproductive fitness in bighorn sheep,” said Deakin.

In trophy hunting, targets are selected based on horn size because of regulations that stipulate only males of a certain horn size – four-fifths curl – can be hunted, with restrictions to bighorn sheep in provincial parks. It is banned in national parks.

According to previous research by collaborators on this study, intense trophy hunting reduced horn lengths in the same Ram Mountain bighorn sheep population.

Monitoring of the sheep at Ram Mountain started in 1971 and is ongoing. The population was historically subjected to trophy hunting of males based on horn size, but in 1996, a more restrictive regulation was introduced, and a moratorium has stopped sport hunting there since 2011.

In Alberta, the hunting season generally runs between late August, or early September in the south of the province, and early October. Management of ‘trophy sheep’ in Alberta allows resident hunters to buy a tag and then hunt for rams that fall under the legal horn size, that is where the tips of their horns are parallel to their eyes. An unlimited number of permits can be sold.

Dominant rams reach their peak at age eight to 10, long after their horns reach the legal age for trophy hunting.

This has led to a gradual decline in horn size over time, said Marco Festa-Bianchet, director of the Department of Biology at the University of Sherbrooke in Quebec.

Festa-Bianchet is a contributor to the study and his research on bighorn sheep at Ram Mountain dates back to 1991.

“We can clearly see a genetic component to the decline in horn size,” he said. “It’s not a huge decline, but it’s about two to three centimetres over the last 40 years.”

Because rams with large horns typically father offspring with large horns, in both males and females, removing dominant rams from the population by selective harvest is affecting both sexes, and therefore could lead to population decline.

“Females have been experiencing a reduction in horn size and we’re finding that females with shorter horns reproduce more slowly or are less fit to do so,” said Deakin. “We can hypothesize that trophy hunting of males is having a trickle-down effect in females.”

If the sheep Deakin studied are typical of the species, the same link between horn size and female reproductive fitness could be happening in other bighorn sheep populations across the province, he said.

It is estimated there are 9,000 bighorn sheep throughout Alberta, 6,000 of which live on provincial lands that are eligible for harvest and another 3,000 that stay in protected areas.

To manage for sustainable harvest, Alberta’s Bighorn Sheep Management Plan (2015) sets a target that seven to 10 per cent of total sheep observed during the last two to three winter surveys should be legal rams with horns four-fifths curl or larger.

Survey results from provincial lands closest to Banff National Park in 2020 are well below this target at 2.8 per cent, but the survey covered only a small proportion of the total Alberta sheep management areas for which the target is established. A substantially higher proportion of legal rams inside Banff National Park – 12.6 per cent – suggests the park is an important refuge for trophy animals that are legally harvested on adjacent lands.

Festa-Bianchet said the population of bighorn sheep in the province is considered stable, however, he has long advocated for regulation changes toward trophy hunting of the animals in Alberta as the evolutionary impacts become evident.

“The harvest rate of legal ram is very high,” he said. “It’s hard to measure but it’s probably somewhere between 40 and 70 per cent.

“So, if your horns are legal in August when the season opens, you’re very unlikely to survive to the rut.”

That in itself is not a huge issue for conservation, he added, though Deakin’s findings regarding the link between horn size and female reproductivity strengthens arguments for a potential need to reassess hunting management practice in the province.

“One way of doing that would be to change the definition of a legal ram from four-fifths curl to full curl, which will leave most rams one or two extra years where they can be in the population and mate,” said Festa-Bianchet. “

“Progress has been very slow, regulations haven’t really changed, but I think it’s important to note from a hunting management viewpoint.”

In response to the Outlook’s request for comment, Alberta Environment and Protected Areas (EPA), said it was interested in reviewing the study results to incorporate best science into the province’s wildlife management policies and strategies.

“Bighorn sheep are an iconic species that are highly valued by Albertans and carefully monitored and managed by EPA,” said communications advisor Jason Penner in a statement. “Our management of hunting for bighorn sheep aims to offer hunting opportunities with strict, selective harvest rules for resident and non-resident hunters, while still ensuring healthy populations and proper ecological function.

“EPA looks forward to reviewing the findings of this study and considering the relevancy and implications for the management of bighorn sheep across Alberta.”

The Local Journalism Initiative is funded by the Government of Canada. The position covers Îyârhe (Stoney) Nakoda First Nation and Kananaskis Country.