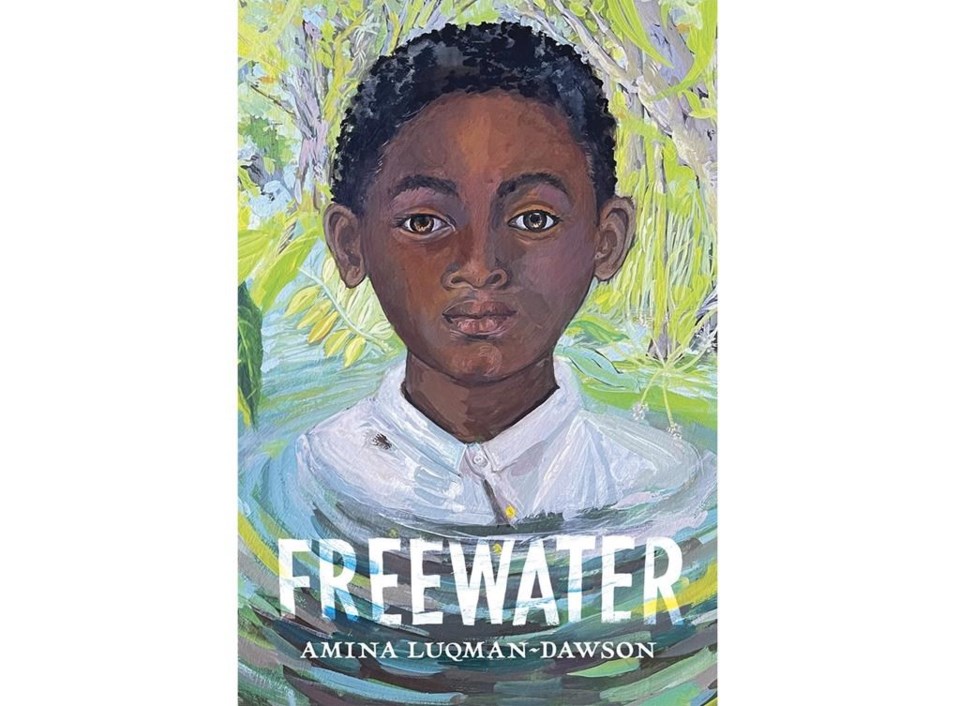

NEW YORK (AP) — For years, Amina Luqman-Dawson made time to write a children's book she calls her "little quiet project," a historical adventure about a community of escaped slaves that she completed while raising a son and working as a policy consultant and researcher on education and domestic violence.

Finding an agent and publisher was the first miracle for Luqman-Dawson and her debut children's story, “Freewater,” which was released last year by a Little Brown and Co. imprint founded by author James Patterson.

On Monday, she joined a tiny elite of children's authors that includes Beverly Cleary, Neil Gaiman and Kwame Alexander: She won the John Newbery Medal for the year's best children's book.

“We have been jumping up and down and screaming,” the 46-year-old Luqman-Dawson, who lives in Arlington, Virginia, said in a telephone interview. Her only previous book is “Images of America: African Americans of Petersburg,” an illustrated work about a Black community in Virginia that came out in 2009.

Doug Salati's “Hot Dog," about the summertime wanderings of an urban dachshund, was given the Randolph Caldecott Medal for outstanding illustrations. Salati, 38, has collaborated with authors Tomie dePaola and Matthew Farina among others, but “Hot Dog” is the first book he both wrote and illustrated. A resident of New York City, he has never owned a dog himself, but was inspired by a dog he saw — belonging to the friend of a friend — while staying on Fire Island.

“I was just watching him be completely free — rolling around in the sand, scratching every itch, zipping down along the beach,” he says. “And that's how I felt being there — a great, beautiful, open space.”

The awards were announced Monday morning by the American Library Association, currently gathered in New Orleans for LibLearnX: The Library Learning Experience.

Luqman-Dawson, who on Monday also won the Coretta Scott King prize for best children's story by a Black author, was able to publish her book with the help of a mentorship program administered by the grassroots organization We Need Diverse Books. She says she had first thought of “Freewater" some 20 years ago, and began working on it more seriously after the birth of her son, Zach, who is now 14. Her hope was to write the kind of story he would want to read.

“I wanted to meet him where he was,” she says, “and (in general) I wanted to find a new way for young readers to access what enslavement meant at that time, what freedom meant at that time and what resistance meant at that time.”

The King prize for illustration was awarded to Frank Morrison for “Standing in the Need of Prayer: A Modern Retelling of the Classic Spiritual," written by Carole Boston Weatherford, who last year won a King award for writing “Unspeakable: The Tulsa Race Massacre.”

Jennette McCurdy's bestselling memoir “I’m Glad My Mom Died” was among the winners of the Alex Award for adult books that appeal to teens. Sabaa Tahir's “All My Rage,” winner last fall of a National Book Award, received the Michael L. Printz Award for excellence in young adult books.

A children's book co-authored by former Olympic gold medalist Tommie Smith and based on his famous protest at the 1968 summer games, “Victory. Stand! Raising My Fist for Justice,” won the YALSA Award for best nonfiction for young adults, and was a finalist for the King award. Smith and Derrick Barnes co-wrote “Victory,” which was illustrated by Dawud Anyabwile.

While many categories highlighted diversity in book publishing, some presenters mispronounced or struggled with the names of honorees, including Anyabwile. Linda Sue Park, a former Newbery winner, tweeted that the ALA should ensure that names are said correctly, calling it “a question of RESPECT.”

The ALA issued a statement Monday afternoon, saying it was “in the process of reaching out to every individual whose name was mispronounced and offering our sincerest apologies for the error.”

It said it provides pronunciation guides to presenters but that “it is possible that some presenters may be coping with nerves in these moments.” The group pledged to better prepare presenters “as we do realize what a major moment this is for the award recipients.”

Claribel A. Ortega's “Frizzy” won the Pura Belpré award for best children's book by a Latino/Latina author, and Adriana M. Garcia received a Belpré prize for her illustration of Xelena González's “Where Wonder Grows." Charlotte Sullivan Wild's “Love, Violet,” illustrated by Charlene Chua, was given the Stonewall Book Award for an outstanding LGBTQ work for children or teens.

Jason Reynolds, author of “Ghost” and “The Boy in the Black Suits"; illustrator James E. Ransome; and Claudette McLinn, founder of the Center for the Study of Multicultural Children’s Literature, all received lifetime achievement honors.

Hillel Italie, The Associated Press