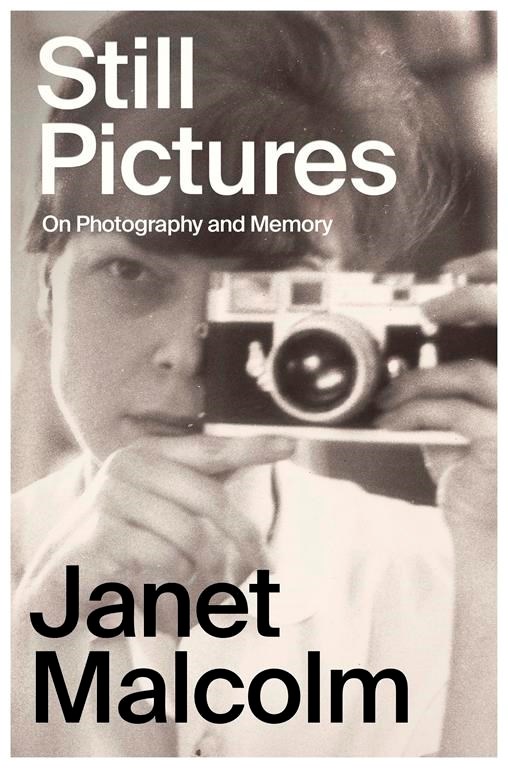

“Still Pictures: On Photography and Memory,” by Janet Malcolm (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

When Janet Malcolm died 18 months ago at 86, her New Yorker colleague Ian Frazier wrote a eulogy for the magazine noting that the famed and feared journalist had been working on a series of essays based on old family photographs. “When the pieces come out as a book we’ll look at them and look at them again and never figure out how such wonders were wrought.” That moment has arrived, and Frazier was right. They are rather wondrous, revealing fascinating and confounding glimpses of an extraordinary life.

Malcolm, who was born in Prague in 1934 and fled to the U.S. with her parents and sister to escape the Nazis, was best-known for her book-length essays on journalism (“The Journalist and the Murderer”); psychoanalysis (“In the Freud Archives”); and the law (“Iphigenia in Forest Hills”).

But she started her decades-long career at the New Yorker writing about interior decoration, design and photography. She was also a photographer, publishing a study of the burdock plant that tried to portray the leaves “as clearly and as cruelly as Richard Avedon photographed individual human beings,” Frazier writes in his introduction to the new book.

Naturally, Malcolm doesn’t take the family photos in “Still Pictures” at face value, just as she never took the supposed objectivity of reporters for granted. “The reportorial eye — and I — are never far from her mind,” her daughter, Anne, writes in an afterword. Both are “transformative” acts. “Even as she tells us a story, she reminds us of her own presence, as the lens through which that naively imagined `actuality’ is being filtered.”

One snapshot shows her, not even 5, with her parents looking out the window of a train leaving Prague for Hamburg, Germany, at the start of their journey to New York. Another depicts her and a teacher at a Czech-language school in the Manhattan neighborhood of Yorkville, where her cosmopolitan parents eventually settled among a large working-class Czech population. Still another one captures her beloved father holding a straw basket near a stand of woods.

Each image sparks “plotless memories,” Malcolm writes, and she refuses to provide them with one. That’s because “memories with a plot” — that is, the ones about conflict, resentment, blame and self-justification —commit “the original sin of autobiography.” And she won’t go there.

As a result, some of the sketches feel frustratingly inconclusive. Nevertheless, simply by trying to describe the photos accurately and capture the complicated cloud of feelings they evoke, Malcolm offers up a vivid portrait of Malcolm, almost in spite of herself.

Ann Levin, The Associated Press