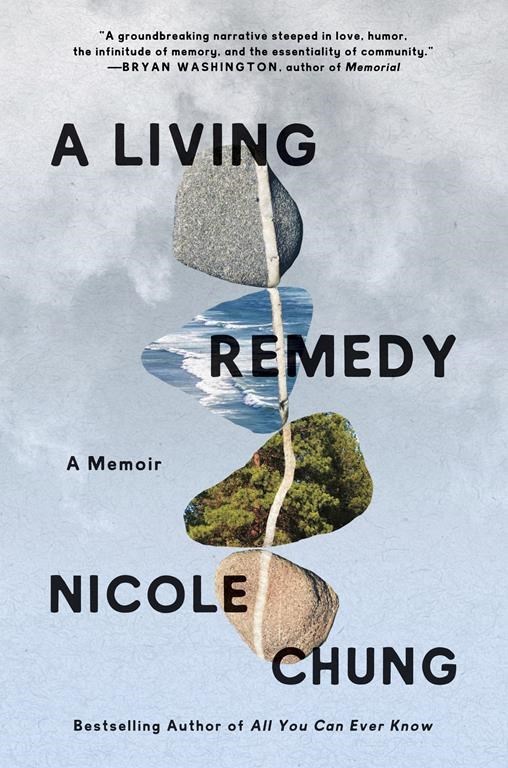

“A Living Remedy,” by Nicole Chung (Ecco)

In 2018, Nicole Chung published the bestseller, “All You Can Ever Know,” about being put up for adoption by her Korean parents and raised by a white couple in rural Oregon. With a few years of finishing the book, her adoptive parents were dead, her dad at 67 and her mom at 68. The latter occurred at the start of the pandemic, when it was all but impossible for Chung, who by then had a husband and two young children of her own, to spend time with her.

Now Chung, 41, a magazine writer who lives in the Washington, D.C. area, has written a follow-up memoir, “A Living Remedy,” about the unbearable grief of watching one parent, then the other, die, and her debilitating guilt about not being able to do more to help them.

When Chung was growing up, her dad managed pizza restaurants and her mom worked mostly office jobs. They had limited or no health insurance, and when he became gravely ill, he was too young for Medicare and too proud to apply for disability. As a young person, she had always thought of herself as middle class. When her parents got sick, she finally understood that they were poor.

“Sickness and grief throw wealthy and poor families alike into upheaval, but they do not transcend the gulfs between us, as some claim — if anything, they often magnify them,” she writes. “It is still hard for me not to think of my father’s death as a kind of negligent homicide, facilitated and sped by the state’s failure to fulfill its most basic responsibilities to him and others like him.”

In interviews after her first book was published, Chung spoke about her desire to give her family some privacy by not identifying her parents by name and offering to change basic identifying details of other relatives. “I always wanted to write it in a way that told the full story but also, as much as possible, honored everybody,” Chung told The Seattle Times.

She has taken a similar approach here. We learn that her dad was an avid Cleveland sports fan, that her mom once had waist-length red hair. But despite her great love for them, the characters never come alive on the page. “A Living Remedy” is most powerful when Chung frames the story of her parents’ deaths as an unnecessary tragedy brought on by the broken health care system in this country.

Ann Levin, The Associated Press