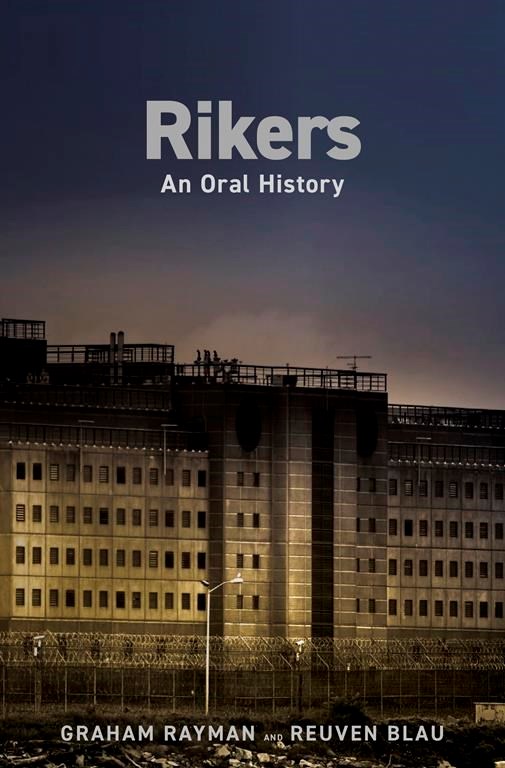

"Rikers: An Oral History," by Graham Rayman and Reuven Blau (Random House)

In these times, when people disagree about seemingly everything, just about everyone interviewed for this book concurs on the thesis: the New York City jails on Rikers Island stand as a failure in every way.

For inmates, a stay at Rikers can be harrowing. Inmate-on-inmate attacks are common — a “buck fifty” in Rikers parlance is a razor slash that requires 150 stitches to close.

How do blades get in? The same way drugs, phones and weapons infiltrate — visitors, incoming inmates and friendly guards. Gangs often emerge as the governance inside.

Rats, mice and roaches infest the place. The smells of vomit, body odor, urine and feces are pervasive. Medical care is uneven at best.

The mentally ill — estimated to be 40 percent of the jail population — suffer the most, preyed on by the stronger inmates and often relegated to solitary confinement.

This book presents the experiences of inmates, staff, lawyers and groups who work with those incarcerated at Rikers. Some held there plead guilty, even if they are innocent, just to get out of the nightmare, said Soffiyah Elijah, executive director of the Alliance of Families for Justice.

Staff, up to and including wardens, offer some of the most compelling critiques.

A corrections officer — the authors say those staffers hate the term “guard” — said he beat an inmate for an hour, including flushing the toilet while holding the inmate’s head in the bowl — all because the inmate “disrespected” him.

At 425 pages, the sheer number of voices in the book sometimes become repetitive and the speakers sometimes are incoherent. Nonetheless, the assembly of testimony presents a powerful portrait of a failed institution. The city had said it plans to close the facility by 2027.

Will the book foster some original thinking on what to do with people arrested, awaiting trial, unable to raise bail, serving sentences for relatively minor crimes or convicted of serious crimes and not yet transferred to state prison?

Political will certainly seems missing in action.

Perhaps the most telling conclusion, and call to action, comes early on in the book: No one comes out of Rikers better than they entered.

“You internalize the dehumanization (and) that’s how you treat other people,“ said Eddie Rosario, who spent part of 1990 at Rikers. “You’re never the same person again.”

Jeff Rowe, The Associated Press