JACKSON, Miss. (AP) — The manager appointed by the U.S. Department of Justice to help fix the long-troubled water system in Mississippi’s capital has an expansive list of reforms on his plate. Over one year, Ted Henifin intends to make substantial progress on all of them.

Henifin will spend the next year managing Jackson's water system after the Justice Department won a federal judge’s approval to carry out a rare intervention to fix the city's water system, which partially failed in late August. People waited in lines for the water to drink, bathe, cook and flush toilets. Many still don't trust the water enough to drink it and haven't for years.

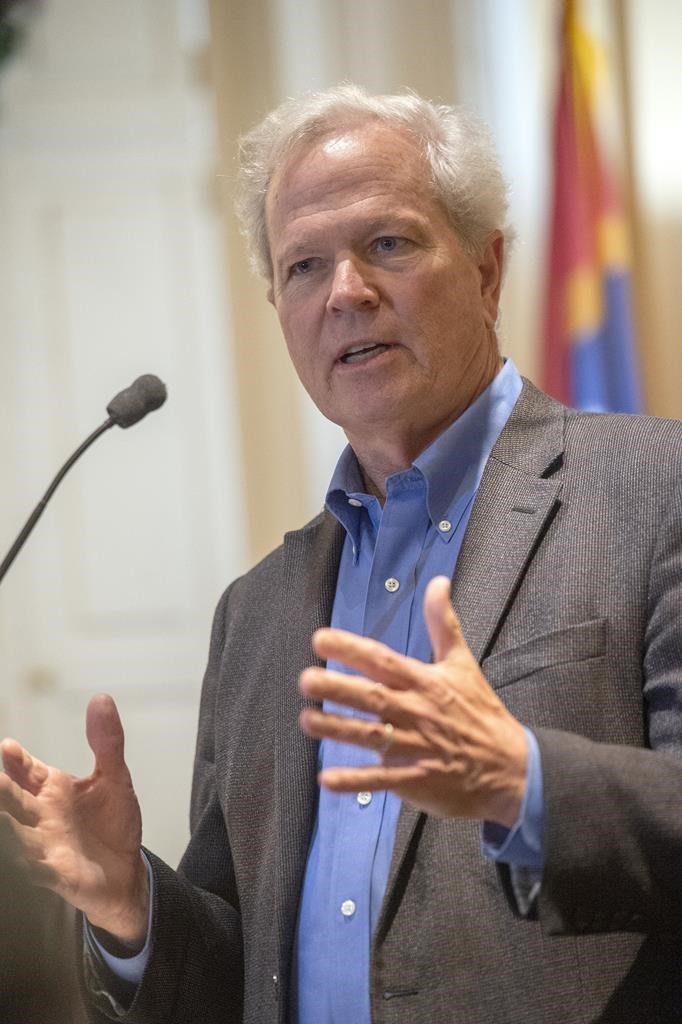

Henifin, who spent 15 years managing a sanitation district in Virginia, has been selected as the figure to shepherd Jackson through a range of technological, legal and political challenges as the city attempts to build a water system that serves its residents for the long haul.

Henifin spoke to The Associated Press about some of the key questions he will face over the next year as he attempts to address the factors that gave rise to the Jackson water crisis. His responses have been edited for brevity and clarity.

___

Q: After arriving in Jackson on Sept. 14 amid the partial collapse of the city's water system, you stayed for two weeks and then returned again in October and November. During those visits, you say you felt a connection with people in Jackson. Why did you feel that connection, and what did community members relay to you about what they were experiencing on the ground?

A: I’d interact with folks when I was in the community. And frankly, the connection was over how they shouldn’t have to live like this. People have largely given up on the drinking water in Jackson. The people I’m talking to didn’t stop drinking the water in August, they stopped 10 years ago. And then they were really frustrated that the pressure varies to the point where sometimes they don’t actually get water at all in their homes. There’s been a lot of talk about the boil-water notices and the challenges with the quality of the water. But you can buy bottled water to drink. When the water actually doesn’t get to your home, you can’t flush your toilet, you can’t bathe your children, and you can’t do anything that you need large quantities of water for. That’s tragic. The connection was feeling that people were so positive about being in Jackson. They love their community. People have largely been beaten down by this inconsistent system. And I felt like, maybe I could make a difference to start the very small steps towards restoring some trust.

Q: Issues with Jackson's water system have bedeviled mayors, state legislators and state executives. Many of these leaders have deep ties to the area. Why might this moment, and the Justice Department's order, catalyze progress that has evaded others who have attempted to fix the water system?

A: I see it as a few key things. You could roll back a little bit to the beginning of the Biden administration and the people he put in place, and the focus he had on environmental justice. And it’s not just EPA, it’s across the board, and it's really not about political views. It’s just that somebody in the White House was really focused on environmental justice across all programs. You had the appointment of Radhika Fox as the assistant administrator for water at the EPA. So we finally had someone who came out of a water utility background, and with an equity perspective. At the same time, a lot of federal funding just happened to be available anyway with the bipartisan infrastructure funds. So all of this, I’d say, created a unique moment in time when you’ve got funding from the federal government at unprecedented levels available for water systems. You’ve got an administration very focused on environmental justice, and with more of a utility perspective than any other group at the EPA has ever had. Then you’ve got the nation’s eyes on the water community coming to help Jackson. The whole country is more focused on water than it’s ever been.

Q: Why was it important for the Justice Department order to include strong liability protections for you and the people who will be working with you in Jackson?

A: In my early days here in Jackson, as I was trying to get folks to help and provide equipment or services, what I ran into a lot was the challenge many professional services companies were seeing from a corporate perspective, and lessons learned largely during Flint. Some of the folks that responded long after the immediate disaster was remediated in Flint got washed into some of the class action lawsuits that were filed against everybody and anybody that was touching the Flint situation. I’m not saying that there weren’t lots of reasons for people to be suing in Flint. And there may be reasons for people to sue Jackson. But I couldn’t even get folks to say they would work with Jackson without some really different protections.

Q: A priority you've laid out is ensuring Jackson provides high-quality water that’s affordable to everyone. How do you think Jackson should approach water rates, and as you oversee water system upgrades, how will you avoid shifting the cost burden toward the bottom of the socioeconomic spectrum in a city where about 25% of people live in poverty?

A: Across the country, we’ve been wrestling with this for years where you try to price water, so it’s affordable for the lowest quintile. We are fundamentally flawed in the United States in that we price water only to burden that lower end of the economic spectrum, and we don’t even attempt to get more revenue from the upper end. That’s because almost every state has some sort of equitable rate requirement in their statutes that says you can’t treat water customers differently. But what if we just flipped the way we billed water so that everyone pays about the same percentage of their income on water? For example, if you look at property values as a surrogate for income, we could generate more than enough revenue to actually own and operate and maintain the system, both water, sewer and distribution system, and have enough money to reinvest and pay debt service. That’s the sort of direction where I’d be looking to take Jackson. We need to find a more equitable method of pricing so we aren’t raising rates for the people who can’t afford it, but we still have to live within state law. And you know, that there may be some real restrictions in how we can make that happen.

Q: You mentioned working with the city and the state, and some of the limitations under state law for adjusting how the city raises revenue. How will you navigate what has been a combative relationship between the city and state leaders?

A: I think an advantage I bring is that I’m not part of Mississippi's political ecosystem. I didn’t really know anything about Jackson’s politics versus the state's politics. So I learned quickly that they aren’t working well together. But I think I could be viewed as a neutral, honest broker between both parties. While they may not talk directly to each other in constructive ways, I think through me, they might be able to get that conversation going, you know. I can sort of shuttle diplomacy, so to speak.

Q: You've talked about the importance of modernizing water infrastructure with technology. What technological tools could Jackson use to improve its water system?

A: What’s missing here is a hydraulic model. In today’s world, you need to really understand what is happening in your system: how the valves are set, where the pressure changes, how the tanks need to be filled and drained, etc. All of that needs to be put into a sophisticated computer model, and many are available today. I really don’t know why Jackson has gotten to the point where they are without that. I called the U.S. Water Alliance and said what we really need is to find someone that can build a hydraulic model. And within hours, I heard Autodesk offered to do it pro bono. They immediately stepped up to start working on a model, and that’s really challenging when you don’t have a lot to give them about where your pipes are and where your valves are. But they’re very close to getting that model working for us.

Q: You intend to finish your work in one year. Is there any flexibility there? And how much progress can you make in one year on the projects you've been tasked with starting?

A: The order is silent on the end date. It’s over when the judge says it’s over. But the EPA and DOJ plan on rolling this into a longer-term consent decree. The goal for the EPA, the city and DOJ is that all the projects are well underway, whether it’s design work or planning before I’m out of here in a year. But as you point out, some of them are going to take years to construct. I’m 63 years old. There’s no way I’m going beyond 65, so it’s going to be a race to a year or less from my perspective. I’ll feel wildly successful if I can finish it up in a year or less.

___

Michael Goldberg is a corps member for the Associated Press/Report for America Statehouse News Initiative. Report for America is a nonprofit national service program that places journalists in local newsrooms to report on undercovered issues. Follow him on Twitter at twitter.com/mikergoldberg.

Michael Goldberg, The Associated Press