WASHINGTON (AP) — U.S. health officials on Tuesday said they would urge food makers to phase out petroleum-based artificial colors in the nation’s food supply, but stopped short of promising a formal ban and offered few specifics on how they intended to achieve the sweeping change.

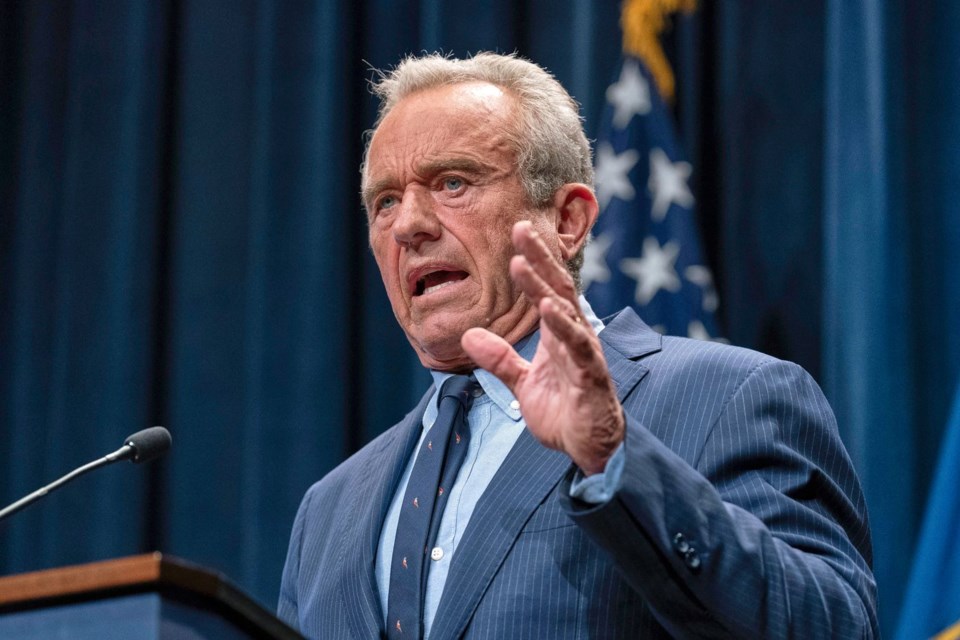

Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Marty Makary said at a news conference that the agency would take steps to eliminate the synthetic dyes by the end of 2026, largely by relying on voluntary efforts from the food industry. Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who joined the gathering, said he had heard from food manufacturers, but had no formal agreements with them.

“We don't have an agreement, we have an understanding,” Kennedy said.

The officials said the FDA would establish a standard and timeline for industry to switch to natural alternatives, revoke authorization for dyes not in production within coming weeks and take action to remove remaining dyes on the market.

“Today, the FDA is asking food companies to substitute petrochemical dyes with natural ingredients for American children as they already do in Europe and Canada,” Makary said.

The proposed move is aimed at boosting children's health, he added.

“For the last 50 years we have been running one of the largest uncontrolled scientific experiments in the world on our nation’s children without their consent," he said.

The process to revoke approved additives from the food supply typically takes several years and requires public comment, agency review and final rulemaking procedures.

Industry groups said that the chemicals are safe and suggested they would try to negotiate with regulators to keep them available.

“FDA and regulatory bodies around the world have deemed our products and ingredients safe, and we look forward to working with the Trump Administration and Congress on this issue,” said Christopher Gindlesperger, spokesman for the National Confectioners Association. “We are in firm agreement that science-based evaluation of food additives will help eliminate consumer confusion and rebuild trust in our national food safety system.”

Health advocates have long called for the removal of artificial dyes from foods, citing mixed studies indicating they can cause neurobehavioral problems, including hyperactivity and attention issues, in some children. The FDA has maintained that the approved dyes are safe and that “the totality of scientific evidence shows that most children have no adverse effects when consuming foods containing color additives.”

The FDA currently allows 36 food color additives, including eight synthetic dyes. In January, the agency announced that the dye known as Red 3 — used in candies, cakes and some medications — would be banned in food by 2027 because it caused cancer in laboratory rats.

Artificial dyes are used widely in U.S. foods. In Canada and in Europe — where synthetic colors are required to carry warning labels — manufacturers mostly use natural substitutes. Several states, including California and West Virginia, have passed laws restricting the use of artificial colors in foods.

The announcement drew praise from advocates who say the dyes carry health risks and serve no purpose beyond the cosmetic.

“Their only purpose is to make food companies money,” said Dr. Peter Lurie, president of the Center for Science in the Public Interest and a former FDA official. “Food dyes help make ultraprocessed foods more attractive, especially to children, often by masking the absence of a colorful ingredient, like fruit.”

Removing artificial dyes from foods has long been a goal of so-called MAHA moms, key supporters of Kennedy and his “Make America Healthy Again” initiatives. They were among protesters who signed petitions and rallied outside the Michigan headquarters of WK Kellogg Co. last year, demanding that the company remove artificial dyes from its breakfast cereals in the U.S.

Health officials insisted that food-makers wanted clarity on the issue and were receptive to the changes, but the response from industry groups was mixed.

Consumer Brands Association, a trade group for food manufacturers, said it had long asked FDA to assert its authority to regulate foods at a national level, rather than leaving it to a patchwork of state laws. But, in a statement, the group also urged FDA officials to “prioritize research that is objective, peer-reviewed and relevant to human health and safety.”

It added that the ingredients in question have been rigorously studied and demonstrated to be safe.

Hours before the announcement, the International Dairy Foods Association said its members would voluntarily eliminate artificial colors in milk, cheese and yogurt products sold to U.S. school meal programs by July 2026.

Other industry groups didn't pledge any quick changes.

The International Association of Color Manufacturers said requiring reformulation in less than two years “ignores scientific evidence and underestimates the complexity of food production. This process is neither simple nor immediate, and the resulting supply disruptions will limit access to familiar, affordable grocery items.”

Removing dyes from the food supply will not address the chief health problems that plague Americans, said Susan Mayne, a Yale University chronic disease expert and former director of the FDA’s food center.

“With every one of their announcements, they’re focusing in on something that’s not going to accomplish what they say it is,” Mayne said of Kennedy's initiatives. “Most of these food dyes have been in our food supply for 100 years. ... So why aren’t they driving toward reductions in things that do drive chronic disease rates?”

In the past, FDA officials said the threat of legal action from the food industry required the government to have significant scientific evidence before banning additives. Red 3 was banned from cosmetics more than three decades before it was stripped from food and medicine. It took five decades for the FDA to ban brominated vegetable oil because of health concerns.

Some of the state laws banning synthetic dyes in school meals have aggressive timelines. West Virginia’s ban, for example, prohibits red, yellow, blue and green artificial dyes in school meals starting Aug. 1. A broader ban will extend the restrictions to all foods sold in the state on Jan. 1, 2028.

Many U.S. food companies are already reformulating their foods, according to Sensient Colors, one of the world’s largest producers of food dyes and flavorings. In place of synthetic dyes, food makers can use natural hues made from beets, algae and crushed insects and pigments from purple sweet potatoes, radishes and red cabbage.

___

Aleccia reported from California.

___ The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Jonel Aleccia And Matthew Perrone, The Associated Press