ÎYÂRHE NAKODA – Language is the foundation of culture and Îyârhe (Stoney) Nakoda First Nation continues to build and fortify its Stoney bedrock, protecting the language for generations to come.

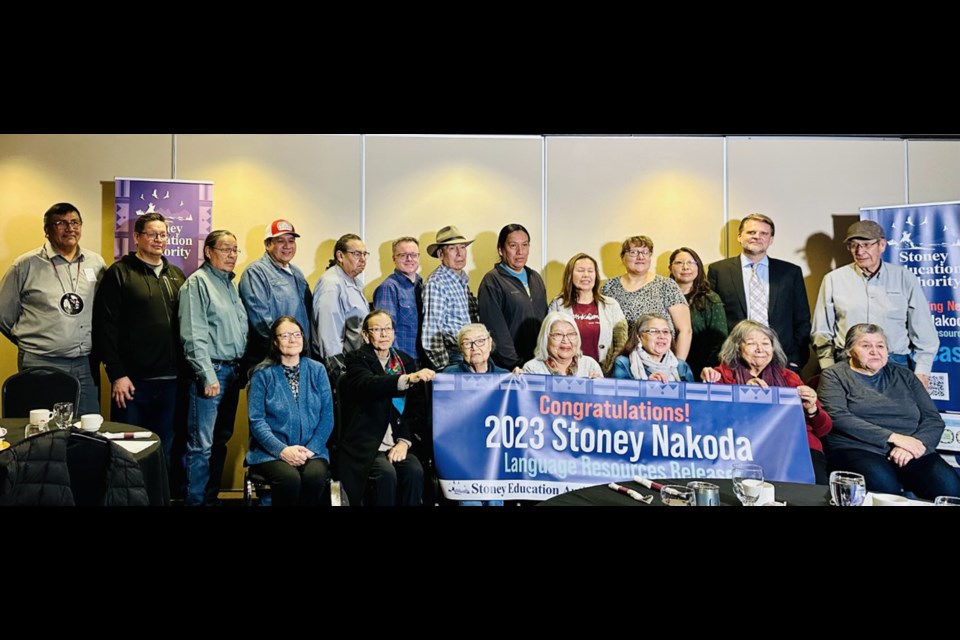

Stoney Education Authority (SEA) was joined by community elders and knowledge keepers on Jan. 23 to celebrate the release of a level two language textbook, student dictionary and Stoney podcast as part of an ongoing initiative with U.S.-based The Language Conservancy (TLC), which aims to preserve the First Nation’s language in written and other forms.

“What we’re trying to do is we’re trying to get people motivated to learn Stoney if it’s not their first language,” said Cherith Mark, SEA language and culture coordinator.

“It’s very critical at this time because our language is considered to be in the realm of endangered as far as Indigenous languages go.”

The new textbook and dictionary will be used in SEA schools across the First Nation during language lessons and expand on a level one textbook that was launched in 2021 with a Stoney media player app that can be used alongside the text.

Phase one of the project also included the creation of colouring and story books, as well as a mobile dictionary app containing over 14,000 Stoney words compiled by Îyârhe Nakoda elders and knowledge keepers in 2019.

Mark said the level two textbook builds from the first text, where it teaches sentences and phrases in Stoney while the other recognizes basic words. The student dictionary is also the first of its kind to be in print but does not include as many words as its mobile app counterpart.

The Stoney Podcast, available to listen to online at stoneynakoda.org/stoney-podcast-directory/, is hosted by Îyârhe Nakoda Elder Terry Rider and is spoken exclusively in Stoney. The show invites other elders in the community to share wanîgas wohnaabi (traditional stories) and waisteyabi (teachings) of the First Nation, and talks about the historical and modern importance of language, land, spirituality, working together and storytelling.

In the first episode, Elder Charlie Rabbit talks about the traditional Îyârhe Nakoda way of life, describing what life was like growing up in Mînî Thnî (Morley) and how it compares to today.

Rider, a fluent speaker of Stoney and host of a morning radio show on CFIR 88.5 FM, was approached by Mark to host the podcast, which has already amassed 14 episodes.

The elder makes a point of speaking to both the young and old in Stoney to pass on as much knowledge as he can and sees the podcast as another means of doing that.

“Most young kids can really pick up the language if they hear it often enough and they’ll speak to you clearly,” he said. “And then there are some who are just learning. But we’re working on it.”

The First Nation has been working to revitalize its language for many years. In 1965, Stoney Tribal Council entered an agreement to develop a writing system for Stoney, due to noticeable language loss in the community from colonial influences.

With an agreed upon alphabet using Roman orthology, the 1970s then saw the creation of the Stoney Cultural Education Program, otherwise known as SCEP.

Rider, a young man at the time, was brought on to the program as a graphic artist. His work, alongside the many elders and others who contributed to SCEP, laid much of the groundwork for the language revitalization work still being done today.

TLC, a non-profit dedicated to preserving Indigenous languages, has been partnering with SEA to create language materials to be used in classrooms, the first of which rolled out in 2021.

The non-profit’s CEO Wilhelm Meya said like many Indigenous languages, Stoney has historically been learned orally through intergenerational language transmission, primarily at home.

“At one time, there was no need to write it,” said Meya. “But as young people are now growing increasingly without Stoney speakers in the household, or without people using Stoney as their first language, it’s not being passed down in those naturally transmitted ways.”

According to the latest available census data in 2016, there were 3,050 people in Canada who identified Stoney as their mother tongue, with 2,550 speakers living in either Mînî Thnî, Eden Valley or Big Horn. At that time, the three Îyârhe Nakoda First Nation communities shared a population of about 4,546 people.

Of those, 4,525 people identified English as their first official language spoken. Another 15 people said neither English nor French was their first spoken language; the census does not specify which language they spoke.

In 2016, there were more Stoney speakers in Îyârhe Nakoda First Nation than there had been in at least 20 years, according to census data. But proportionate to the First Nation’s population growth – Stoney, like so many other Indigenous languages, has been on the decline.

Data from the 2021 census could not be compared as Stoney Nakoda First Nation chiefs and council did not give Statistics Canada surveying permission, thus no information is available.

For Indigenous oral societies, words hold knowledge amassed for millennia. Stories, songs, dances, protocols, family histories and connections are one with the language, making it all the more important to protect, especially as the population ages.

Rider said it makes him proud to see his grandson learning Stoney in school and using textbooks that encourage learning and use of the language. It is a far cry from the days of residential schools where the use of Indigenous languages was not allowed, and in some cases, punished.

Eventually, Rider said he hopes to share stories from the Stoney podcast to his radio show to further its reach in the community and to others who wish to learn about the Îyârhe Nakoda, with respect to their intellectual property. The new Stoney student dictionary will also be available for purchase to those interested by calling the SEA office at 403-881-2743.

By having many language resources available and actively being used by students in the community, Mark hopes what has been a downward trend in fluent Stoney speakers over the last number of years will turn itself around.

Work will begin soon on an advanced, level three Stoney textbook and other upcoming materials could include cartoons in Stoney, children’s books, e-learning opportunities, or anything else that might contribute to the language’s preservation over time.

“Even though we do speak it openly out in the community, the transfer of knowledge isn’t quite where we want it to be yet,” said Mark. “Which is why this work is so important.

“Once it’s all written down, then it’s in print and that’s something that will go on forever. Going forward, we just need to keep at it and create more ways for people to learn and be excited about this.”

The Local Journalism Initiative is funded by the Government of Canada. The position covers Îyârhe (Stoney) Nakoda First Nation and Kananaskis Country.