It's a new beginning for Nakoda Elementary School, or a continuation of the way things have always been, depending who you ask.

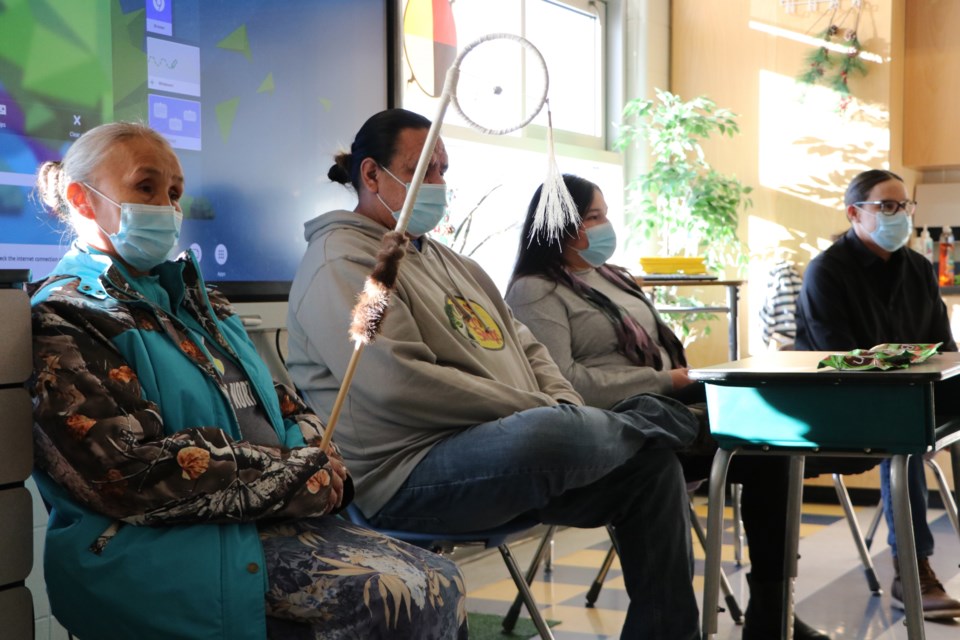

About three weeks ago, the school started a partnership with a panel of Stoney Nakoda elders and knowledge keepers, inviting them in each week to pass on their teachings and lived experiences to young students.

"We wanted to make sure that language, culture and the Stoney traditions were a part of the lessons, the day, the life, of all of our kids," said school principal Aimee Dixon.

Dixon said the school has tried to get elders there in previous years, in fact, they were just beginning to pick up momentum in getting a program started prior to COVID.

Although students are still attending classes in cohorts, Dixon was able to get the ball rolling again when she reached out to Gabriel Young earlier this year, co-coordinator of the Îyârhe Nakoda Youth Program's Honouring Life Day Camp.

The summer day camp brings youth out on the land to learn how to hunt, fish and build with elders and knowledge keepers using tools and techniques traditional to the Stoney people.

"Instead of reinventing the wheel, I reached out to Gabriel and suggested partnering up, knowing that he had already made these connections," said Dixon.

Among those connections are Stoney Nakoda elders Watson Kaquitts and Jackie Rider, who have now become an important part of the school's program as well.

"As Stoney's, we're some of the last [Indigenous people] where some of us can speak our own language," said Kaquitts. "Even little kids used to play around talking our own language and we're losing that."

Kaquitts said he believes an important part of youth on the Nation receiving a good education should be a balance of speaking both languages.

"That's what our elders used to say - my mother used to tell me to never lose my language, never lose my roots, our ways of living," he said.

Kaquitts grandfather also used to tell him stories from long ago, when they used to chase buffalo on horseback - but the important details of such a story can sometimes get lost and reduced to just that, leaving no explanation for why they did things a certain way, he explained.

"They would also put on a ceremony before that hunt for the safety of the people and the horses," said Kaquitts, who like many elders, plays a key role in keeping ceremonial traditions alive within the Nation.

By building knowledge of their culture, language and traditions, they are also providing a lesson in identity and ultimately, mental wellness to the Nation, said Young.

"Culturally, traditionally, morals and wellness tools were taught orally by the elders," he said. "So I think part of this partnership is to provide those cultural teachings where it's a blend between our oral history, and all that leads to building identity.

"I think it's important to merge the written world with our world," he said. "The outcomes of this is to strengthen the identity of who we are as Stoney people."

When he was a boy, Young said his access to elders was at home.

Although the program is only in the school for half-an-hour per class each week, sometimes more, it's important for the youth to not only hear but be heard, he said.

"To have access to ask these elders questions and to have that opportunity for that engagement to happen, I think it's an important part of why we're here."

Conversations in the classroom are started by passing around the "talking stick," giving everyone an opportunity to speak and ask questions that can range from teachings about what they're ancestors did to stay safe during storms and asking and answering questions about residential schools.

Îyârhe Nakoda Youth outreach worker Earl Labelle said the student's have a keen interest in learning and will often ask follow up questions during lessons to continue expanding on a topic until they feel they understand it well enough.

"We get questions like 'how did you used to hunt?' and we'll tell them on horseback with bows," he said. "The following week [the students] will come back and ask how we'd make the bows. So we explain it, how we went about it, and eventually they started to understand it more. Before life with guns, they used bows, made tools out of everything - the entire animal - they all know that now.

"But they keep asking similar questions that are related to the topic, so their curiosity is ever-expanding," he said.

The program aims to become more hands on in the summer when students can be outside making things and learning the oral histories of what they're making and why - such as drums, bows, or smokehouses, for example.

Currently, the program is available to Grades 3 to 5, who receive one or two lessons a week due to their cohort set-up. In the new year, they plan to roll it out to the rest of the school's student body in pre-kindergarten to Grade 2.

Dixon and the program crew also hope to further expand their panel by bringing in more elders and knowledge keepers, providing access to a more complete representation of their community to students.