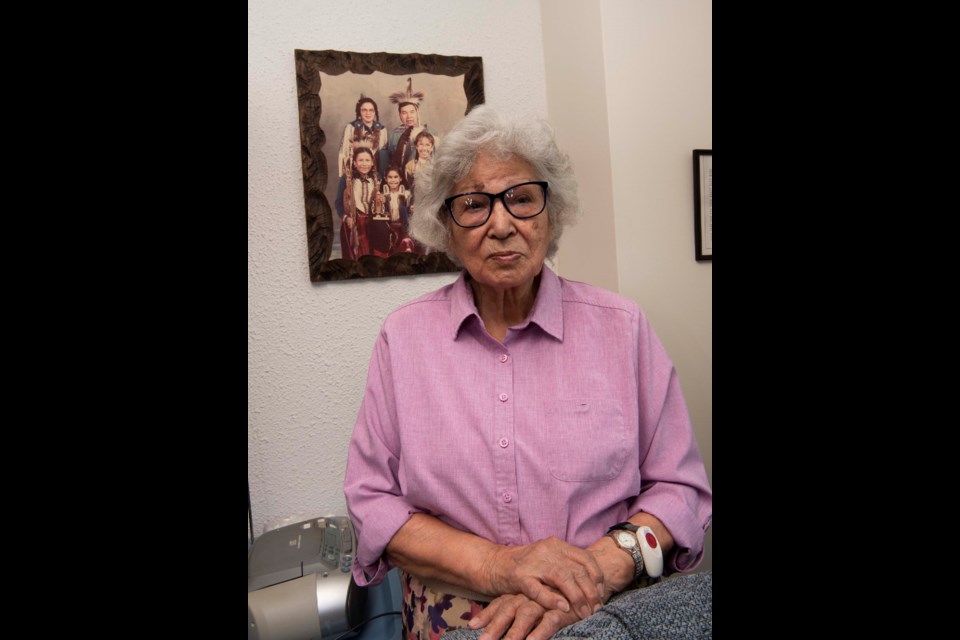

St. Albert - When news broke last month of the 215 children found buried at the former residential school in Kamloops, it brought back many painful memories for Edmonton’s Marguerite Auger.

Auger was one of the roughly 150,000 First Nations, Indigenous, and Métis youths forced through Canada’s residential school system — in her case, the Youville school in St. Albert, which she attended in around the 1940s.

Auger said she never told her three adopted children much about her time in the school — about the brutal discipline, terrible food, and the possible murder. Now 91, she wanted to share her experience to make sure no one else would ever go through anything like it again.

“I’m hoping to get some healing from this.”

St. Albert was home to two residential schools: the Youville school on Mission Hill (operational from 1863 to 1948) and the Edmonton/Poundmaker one on Poundmaker Road (1924-1968). In the wake of the Kamloops discovery, The Gazette asked one survivor from each school if they wished to speak about their experiences.

Going to school

Now 89, Myrtle Calahaisn grew up in Saddle Lake Cree Nation and went to the Poundmaker school from about 1937 to 1946.

Calahaisn said the local Indian agent told her mother that she and her brother, Benjamin, were required to go to the Poundmaker school.

“My mother must have told him we had no clothes,” she said, as the agent took them into town to buy clothes for the train trip west.

Calahaisn, then five, said she recalled having fun on the train as she didn’t know what was going on. She suspects her brother knew, as he was quiet the whole trip.

Eventually, they drove up to a big brick building, and were escorted inside. School staff stripped them of their clothes, which they never saw again, and sent them to separate girls’ and boys’ wings of the building. From then on, Calahaisn would be separated from her brother by a wire fence.

Calahaisn’s mother worked for one of the priests at the school, but was not allowed to visit her children. Every Friday, though, she would get into a car in front of the school and leave for the weekend. Calahaisn, lifted up by one of her cousins, would see her through the basement playroom window.

“That was the only way I got to see my mother,” Calahaisn said.

Auger said her mother wanted her to go to a conventional school in Morinville, but was threatened with jail time if she didn’t send her to the Youville.

Auger said she and other Enoch Cree Nation youths got to spend their summers at home. At the end of August, the nuns would arrive to collect them. She recalled how the mothers would cry as the children were taken away, and how the little kids would burst into tears when the big brick convent on the hill came into view.

Auger said the nuns drove the students to St. Albert using a black van with three lengthwise benches and a tiny window in the back.

“We called it the Black Maria,” said Auger, using a British term for a prisoner transport.

“That’s just how it felt to me: we were going to jail.”

Grief, cruelty, and death

Like many residential school survivors, Auger and Calahaisn said their time at school was light on education and heavy on labour and cultural oppression.

Auger did not initially know English, and was punished for asking others in Cree what the teacher was saying.

“The nuns put plasters on my mouth like this,” she said, making an “X” over her lips.

Auger’s education was hampered by the fact the headmistress refused to believe she needed glasses — she had to copy her notes from her brother as she couldn’t see the blackboard. When she finally went to an optometrist at 18, the man said to her, “I don’t know how you ever managed to get through school like this.”

Calahaisn said the nuns at Poundmaker school would punish students by cutting their hair short, which went against the Indigenous tradition of long hair. She recalled a lot of fights at her school, and often saw students crying to themselves in the corner.

“It was an awful place.”

Calahaisn said her cousins at the school taught her to scrawl her name, defended her from bullies, and lifted her up to use the sink (the lip of which was at the level of her forehead). She left the school with only a rudimentary knowledge of English, and had to pick up the rest in conventional public school.

Auger said she and the girls had to make their beds and dust all four flights of stairs in the school every morning. Older students would help out in the kitchen; she recalled standing on a stool while whipping a cauldron of white sauce, and rolling out pastry for scores of mincemeat pies.

Calahaisn said the girls would spend about half the day in class and the other half in the sewing room darning socks. Boys such as her brother had to do farm work, and dig holes deeper than they were tall that would mysteriously be filled up the next day — likely graves.

Terrible food was a common feature in the lives of many residential school survivors, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission found.

Calahaisn said sticking a spoon into her morning porridge felt like hitting a plank. Auger recalled how the nuns forced her to clean her plate, even if she gagged and cried, and would sometimes serve up rotten fish or mincemeat pies fouled with mice droppings.

“To this day the smell of mincemeat pie brings memories, and (they are) not good,” Auger said.

Many residential school survivors reported brutal discipline at the schools, the commission found.

The nuns at the school would punish you for even the slightest infractions, Auger said. One time, a sister of a nun loaned her a coat to wear so she could stay warm while cleaning the cold storage room. When the nun saw her in the coat, Auger said the nun started pounding her in the back with fury in her eyes, causing her to fear for her life.

In another incident, Auger said she and the girls had lined up when a nun noticed one of them, a seven-year-old orphan, not doing so properly. The nun shoved the girl down the stairs. The girl died in hospital from the resulting injuries.

“Now, do you call that an accident or a murder?” Auger asked.

Auger and Calahaisn had few positive memories of their time in the schools. Auger remembers being excited to go home each summer, and how one nun let her feed some dogs at the back door some bread soaked in roast-pan drippings.

Calahaisn spoke of how one time her brother sneaked into St. Albert and came back with a bag of candy for her, which he tossed over the wire fence.

“The paper bag broke,” she said, scattering gumdrops and chocolates everywhere.

Calahaisn and her cousins crawled around in the grass picking up candies as a nun yelled at them from a high-up window to get away from the fence.

“We had a good feed anyway that day.”

Life beyond the schools

Like many survivors, Auger said she came out of the Youville school having forgotten how to speak Cree. She relearned while in treatment at the Charles Camsell Indian Hospital, where other patients mocked her as a “black woman white woman” (i.e. someone not truly of her race).

The residential schools left generations of Indigenous Canadians without proper parenting skills. Auger said she carried the Youville school’s strict discipline with her as a foster parent. After one child reported her to a teacher for striking her, the school helped her take a parenting course.

“It’s a vicious circle,” Auger said.

“In the convent, we never got hugged, we never got patted on the back. I don’t remember receiving a nice compliment. I didn’t know how to do that. I didn’t know how to be a parent.”

Auger said she went on to foster some 52 youths in 19 years. She adopted three of them and travelled the world with them and her second husband, Lloyd.

Like Auger, Calahaisn never finished high school, instead working as a dishwasher and housekeeper for most of her career. She raised nine children with her husband, Walter.

Calahaisn said she and her husband never talked much about their school experiences with their children. Instead, they vowed to do all they could to ensure their kids never went through the life they lived.

“It robbed me of my childhood. It robbed me of having a regular family life with my mom.”

Calahaisn said she agreed to speak with The Gazette after hearing other survivors share their stories. She wanted today’s youth to understand how good of a life they have lived.

“It was not a good life in residential school.”

When asked what Canadians should do after having heard of their experiences, Calahaisn and Auger said they should treat those around them with compassion instead of showering them with racist epithets.

“Lift them up,” said Auger.

Other accounts from residential school survivors can be found at The National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation website (nctr.ca).

Read more from StAlbertToday.ca