INNISFAIL – Ryan Jason Allen Willert sits comfortably smoking a cigarette and drinking a soda on a deck surrounded by trees that rustle softly from a gentle southern breeze.

At 38-years-old, he’s a citizen of the Siksika Nation – part of the Blackfoot Confederacy.

He has a good life today. Ryan is an accomplished Indigenous artist. He’s married with a child coming soon.

Ryan reminisces the good parts of his life in Innisfail where he was raised by his single, white mother Barbara.

“I had a lot of good memories, especially when I was a kid,” said Ryan, who was born in Olds but raised in Innisfail for the first 15 years of his life. “That's the one thing about a small town is that you can get on your bike at a very young age and ride around town; go to the stores, the theatre, pool, parks and go tobogganing. These are good memories that I have there.”

But these good memories are ones he only embraced after he decided to let go of the bad childhood ones that made him feel unworthy and hopeless. He had to face the storm.

“I want to be happy. I don't want to be sad. I don't want to be angry,” said Ryan, who now lives in Red Deer but frequently visits Innisfail.

“There’s definitely hope. You’ve got to have hope in life,” he said about any changes he might see in the community. “And I have faith that hopefully people will live in the now. But how are they going to live in the now if they don't have direction or teaching to do so?”

Community healing

During the afternoon of June 18, the Innisfail Welcoming & Inclusive Community Committee hosted a Blanket exercise at the Innisfail Library/Learning Centre that was facilitated by Michelle Nieviadomy, an Edmonton wellness advocate and member of the Kawacatoose First Nation in Saskatchewan.

The goal of the exercise was to examine the nation-to-nation relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples of Canada. The ceremony was designed to help participants understand how colonization impacted Indigenous citizens who lived and worked the land long before settlers arrived.

Blankets were arranged on the floor to represent land across the country. Exercise participants were invited to step into the roles of First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples as the historical record of claimed land unfolded.

“I think this is more of a story for non-Indigenous people that they need to hear. It has to. We know our story. We've walked through it. We've lived it,” said Nieviadomy, fully aware of this month’s visit by Pope Francis to the region but adamant the stories told on June 18 were the priority. “We're not waiting for the pope to apologize. We're going to just continue to do what we do to heal and tell this story.

“But I hope he (pope) really hears the story,” she added. “I hope he hears the cries of the land.”

Thirty-one Innisfailians attended, including all members of town council.

When the exercise was over everyone shared their thoughts and stories. Gordon Shaw and his wife Angela were also there. He told everyone his story of reclaiming his Indigenous heritage.

Cindy Messaros, a longtime resident and community builder, shared a story about how her late mother Sherida became close to area Indigenous people; a relationship that earned her the Indigenous name of South Wind in 1977.

“I was proud because of the friendships and relationships she made with the Indigenous population at her work. As a result of that, my brother and I got invited to ceremonies and powwows and sweet grass ceremonies and rodeos and hockey games,” said Messaros. “It was an early exposure to their culture.

“We were never brought up with that idea of discrimination against Indigenous people,” she said, adding the Blanket exercise was a “nourishing, moving and profound” experience towards greater understanding of how Indigenous citizens lost their land and culture.

“It helps to speak to people who don't know any better about the situation of the indigenous people.”

Raising the teepees

Both the Chinook’s Edge School Division and Red Deer Regional Catholic Schools have ongoing, developing Indigenous curriculums for students, whether it be through history and storytelling, art and dance presentations or Blanket ceremonies.

There’s also thought given to staff on the reconciliation process. In late spring, Indigenous elders offered teepee teachings to Chinook’s Learning Services staff during a day-long professional development session.

Jason Drent is the school division’s associate superintendent of learning services. He said reconciliation is a journey for the school board, and with the pope in Canada this month it’s another small step but an important one.

“I think we're excited as new curriculum comes out for opportunities for us to relook at ways that we can embed some of this as an organization,” said Drent. “I think at the end of the day the piece that I'm most excited about from an education standpoint is our students can actually see the Truth and Reconciliation recommendations actually coming to reality.”

There are 94 calls to action from the Truth and Reconciliation report. The pope’s apology on April 1 was number 58 out of 94 calls to action.

However, the pope’s Canadian visit was not a primary focus during a teepee raising ceremony at St. Marguerite Bourgeoys Catholic School on June 17.

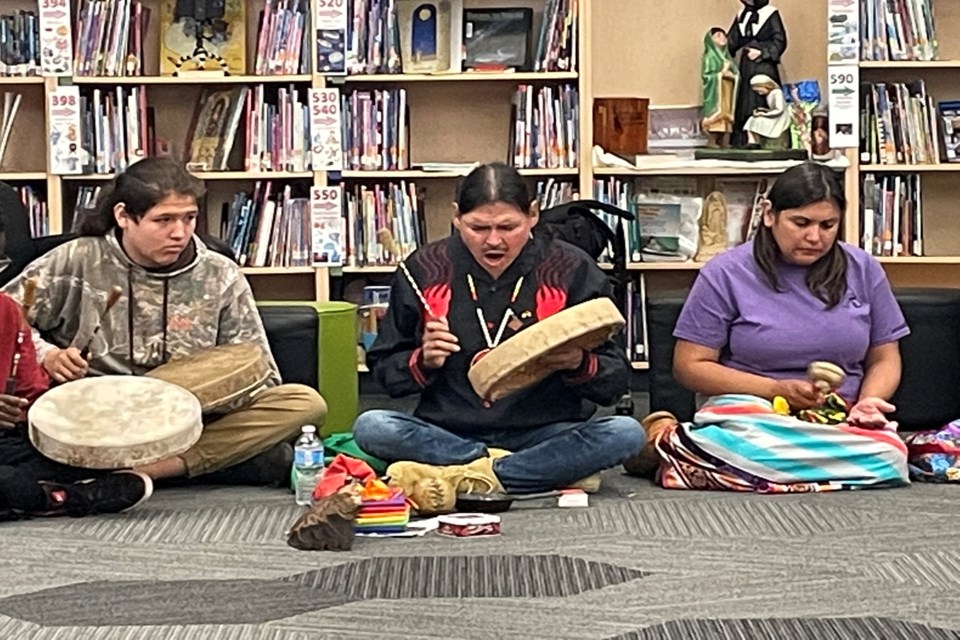

The entire school was involved. The event, led by Indigenous knowledge keeper Dean Allen Johnson, was held in the school library with every class arriving in shifts to watch the process. It was also live-streamed for the community to watch.

“What's happening today is about moving forward, and how we can find that energy to get along, because it's in all of us whether we want to acknowledge it or not,” said Johnson.

Everyone attending the ceremony had a hand in building and raising the teepee, from school board staff, teachers, and Indigenous instructors.

Dave Martin, assistant principal at St. Marguerite, said the completed teepee will be a permanent fixture inside the school’s library, an ever-constant reminder of the energy Johnson believes in.

“I'm sitting here watching the ceremony, and I'm in awe of the beauty, the awesomeness, and the culture that's there. And then I just thought that it breaks my heart that at one point in time we were trying to stop this culture,” said Martin. “History taught us a long time ago that this culture was dirty and wrong. And I did not see that. I see beauty.

"As knowledge keeper Dean says, ‘a oneness that we're all in this together.'”

Forgiveness

The storm Ryan Jason Allen Willert once faced is behind him now but never forgotten.

He grew up half-white. His grandfather on his mother’s side was also white. He did not meet his Indigenous side until he was 18.

“I was not raised by Natives but yet I was always reminded about how non-white I am. I wasn't very proud to be native,” adding he faced many racist slurs, was depressed and even suicidal. “I'd go to my one friend’s house and his dad would always make jokes and say, ‘non-Caucasians eat last, Caucasians eat first’. And so, he would serve his Caucasian kids first and then make me eat last.

"And then they would make fun of me about being native all the time.”

He left Innisfail when he turned 15. He got into trouble with the law. He wound up in a Red Deer group home.

Two years later he hitchhiked to San Diego, lived on the streets for a while and came back to Red Deer. He was soon thinking about heading back to California but his mother intervened.

“My mom got scared for me, that she was never going to see me again. She said, ‘it's time for you to meet your native family,” he said.

Ryan met his father on the streets of Calgary. It was a tough life there but at last he was with people who understood.

“I lived on the streets with them, and I related to them because we're native. They were full Blackfoot.”

He also found art and sold it on the street. At the age of 30 he discovered traditional native ceremony. He also sobered up, and has not had a drink in eight years.

But Ryan needed to face the storm. He also had to embrace its path towards forgiveness.

“The buffalo, out of all animals, charge into the storm instead of away from it,” said Ryan.

He said his Indigenous Buffalo teachings maintain there are four ways to be a buffalo: taking responsibility for your actions, saying sorry when it's due, forgiving yourself, and forgiving others.

“You can't move forward in life holding on to things in order to be happy. I got to let go of it. I have pain. White people have hurt me, and I've also been hurt by my own people,” said Ryan.

“I want to enjoy life, and the only way to do that is to charge through that storm.”