No one expected “Bring It On” to win its opening weekend. The Kirsten Dunst and Gabrielle Union teen cheerleading comedy was facing off against a $60 million Wesley Snipes action film. But on the weekend of August 25, 2000 the $10 million pic about the Rancho Carne Toros and the East Compton Clovers skyrocketed to No. 1 and stayed there for two weeks.

“Bring It On” has been defying expectations since the beginning, when it was still called “Cheer Fever” and getting first-time screenwriter Jessica Bendinger nothing but “no’s” from the studios (27 in total).

Not only was it a hit of its time (that spawned five direct-to-video sequels) but 20 years later is just as relevant as ever for its prescient themes and young fans from Ariana Grande to Jerry Harris of the Netflix phenomenon “Cheer."

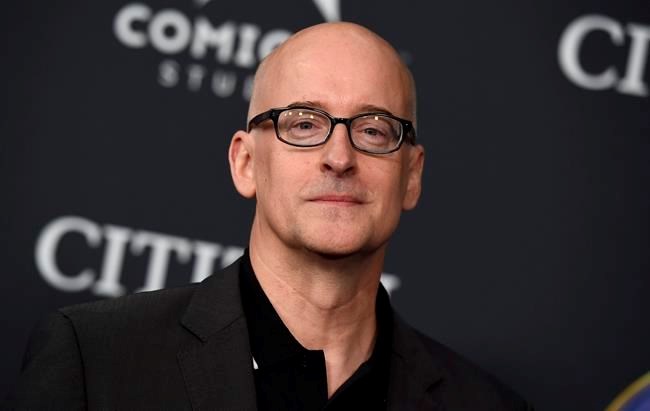

The Associated Press spoke to Bendinger and director Peyton Reed about making “Bring It On.” Remarks have been edited for clarity and brevity.

___

AP: What was the story behind changing the title from “Cheer Fever” to “Bring It On”?

REED: There was a studio attitude that the word “cheer” was going to narrow the audience too much and that people might just think it’s a cheerleading movie. And I’m thinking, “Well it IS a cheerleading movie.” But they came up with lists to encapsulate the attitude of the movie.

BENDINGER: I think it was a big wrestling call out back in the day, like “bring it on.” I thought it was kind of funny.

REED: I liked the confrontational aspect of it. But there is that scene with Gabrielle when she says to “bring it” in the final. I remember having to wrap my overly logical head around “Wait, she says ‘bring it’ she doesn’t say ‘bring it on.’”

AP: Did the $10 million budget feel like a lot, or enough?

REED: It never seems like a lot but it also felt like, that’s cool, this is going to be a scrappy movie. We were all so enthusiastic about making it. We knew in relation to other movies at Universal that we were small potatoes but that gave us a certain amount of freedom. We were off their radar a little bit.

BENDINGER: I remember going down to Oceanside, California, to film the nationals and thinking wow, this is actually pretty impressive.

REED: We made Oceanside look like Florida except the ocean was on the wrong side.

AP: Did the script change much from when you started pitching in 1996?

BENDINGER: I’ve been revisiting my youthful indiscretions in writing form because I’m publishing the screenplay for the first time with some never-before-seen scenes. I had like six endings. But Peyton saw the David in the marble.

REED: That first draft would have been a sprawling, three-hour cheerleading epic.

AP: Is anything you wish you could change?

BENDINGER: We did try to put nuance in it that whole thing with Jan and Courtney and the “digits that slip” occasionally. It was a very ambitious way to talk about slut-shaming, in my mind. When I see that now, it’s awkward for me and uncomfortable. In a teen comedy, it’s just not reading that way even if it was our intention.

REED: I think any time you try to push boundaries, there are things that age well and things that don’t.

AP: Why do you think “Bring It On” gets referred to as a cult classic when it made so much money ($90.5 million) at the time?

REED: Jessica has theory that made sense to me. And it was basically like a high percentage of guys who talk to us about the movie come up and say, “Listen, I know it wasn’t targeted at me but...”. They qualify their positive feelings. Maybe it’s a cult movie because guys are embarrassed to admit they like it.

BENDINGER: And we made it for everybody! I think that there’s some internalized surprise or shame for guys like they can’t believe they like this movie that so clearly seems like it made for young women. But, and this is a little saltier, I feel like saying “oh really, I was writing young teenage girls in cheerleading outfits and you really thought that wouldn’t be for you?”

AP: Did you read reviews when they came out?

REED: I have to admit, I was pretty obsessive.

BENDINGER: I remember refreshing to see if The New York Times online had posted. The A.O. Scott review came up at some point and I burst into tears that he got it.

AP: Roger Ebert basically used his to rail against the MPAA and the PG-13 teen comedy.

BENDINGER: There’s a story there. I’m from Chicago and Roger Ebert was a

REED: The Citizen Kane line came later! Ebert wrote the review and reassessed it. Maybe your dad got through to him.

AP: Is there anything you’re particularly proud of?

REED: The whole notion of cultural appropriation. If you sort of look at it through today’s lens, Kirsten’s character is really confronting her own white privilege. It’s one of the great strengths of Jessica’s script.

___

Follow AP Film Writer Lindsey Bahr on Twitter: www.twitter.com/ldbahr

Lindsey Bahr, The Associated Press