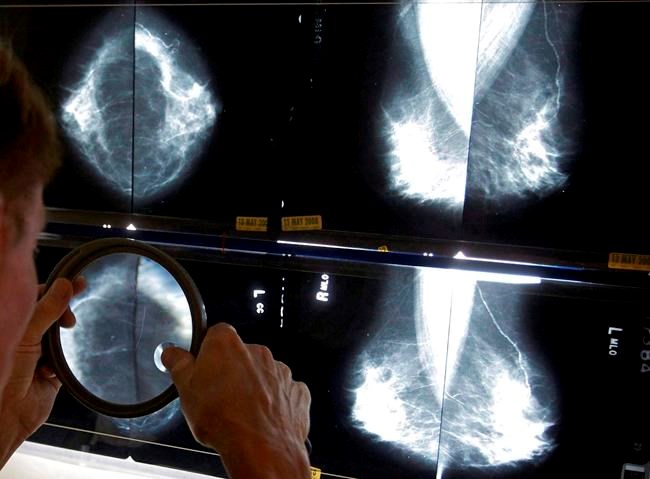

New Brunswick is the latest province to mandate that women be told their breast density following a mammogram, but experts say the welcome move falls short of a broader breast cancer strategy they'd like to see extended coast-to-coast.

Jennie Dale of Dense Breasts Canada says the measure is an "amazing first step," but she pointed to inconsistent reporting protocols across the country and uneven access to alternate screening tools that women with dense breasts might require.

New Brunswick said Wednesday that provincial cancer screening sites must include breast density information in the mammography result letters they send to patients aged 50 to 74.

Health Minister Dorothy Shephard said the measure will allow women to better monitor their breast health since those with high density are at higher risk of cancer.

Dale called on the province Thursday to also offer women with very high-density breasts follow-up screening via ultrasound, because signs of cancer look very similar to dense tissue and can be hard to detect solely by mammogram.

"Mammograms are not necessarily enough for women with dense breasts," says Dale, who credits an ultrasound with discovering her breast cancer at an early stage in 2014, allowing her to avoid chemotherapy.

"Women may get the all-clear but really there's a cancer there."

New Brunswick joins British Columbia, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and Alberta in telling women about their breast density, whether high or low, says Dale.

She says Newfoundland and the Yukon are expected to join the list next year, and that Manitoba and Saskatchewan will extend their reports next year to all screened patients, instead of just those with very dense breasts, as is the current practice.

Dale says gaps exist in Quebec, which only notifies the doctor but not the patient, and Ontario, which only notifies women with very dense breasts.

Breast density is measured in four categories, with women in the highest category four-to-six times more likely to develop cancer than those in the lowest category.

In Ontario, about 500,000 women in the second-highest category of breast density are not automatically told of their increased risk, information Dale says could push some women to mitigate lifestyle risk factors including weight gain and alcohol use.

"Those women need to know so that they don't have a false sense of security and that they need to be vigilant about checking their breasts, they need to know that an ultrasound could be a benefit to them, they need to know that they're at increased risk and maybe they will mitigate lifestyle risk factors," says Dale, noting density is one of many risk factors for breast cancer.

About 10 per cent of women are in each of the lowest and highest ends of the breast density spectrum, with about 80 per cent in the two middle categories, says Martin Yaffe, a senior scientist at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre.

He describes dense breasts as "a double whammy" because it puts those women at greater risk of cancer, but also makes it harder to detect cancer by mammogram.

But Yaffe says it's also important for women to know if they have low-density breasts, because that can assure them a mammogram exam was complete and that their doctor didn't have to struggle to look for signs of cancer.

While most provincial screening programs encourage women between ages 50 and 74 to be screened every two years, Yaffe suggests women begin screening annually at age 40 until menopause, and every other year after that.

"Breast cancers tend to be more aggressive in younger women, and waiting two years or more in between screens, I think, is not a good idea," says Yaffe.

The pandemic has further complicated screening by extending wait times and backlogs, even though many provinces have resumed non-urgent procedures, says Yaffe, who just completed a soon-to-be-published study on the impact of halted screening for breast cancer and colorectal cancer.

Even if a woman lives in a province that doesn't reveal breast density, it might be possible to know, says Dale, but the onus is on the patient to chase that information.

She says the radiologist may have included details under general findings in the report, which a patient can ask their doctor about.

Dale says there is a push in Ontario to make such notations mandatory but it has been a struggle to get 100 per cent compliance.

"In the other provinces it had to be mandated," she notes. "In B.C., they had asked the radiologists for 30 years — seriously 30 years since the pre-screening program started — to comment on the density, to put it in the report."

Dale says there is other technology she would like to see used more widely in Canada including 3D ultrasound, contrast enhanced mammography, and abbreviated MRI.

But more awareness about breast density is key for doctors and patients, she stresses, as well as easy access to ultrasound screening for women with highest density.

"It's called additional screening but it really should be called essential screening," she says.

"It's dangerous not having that additional test."

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Nov. 5, 2020.

Cassandra Szklarski, The Canadian Press