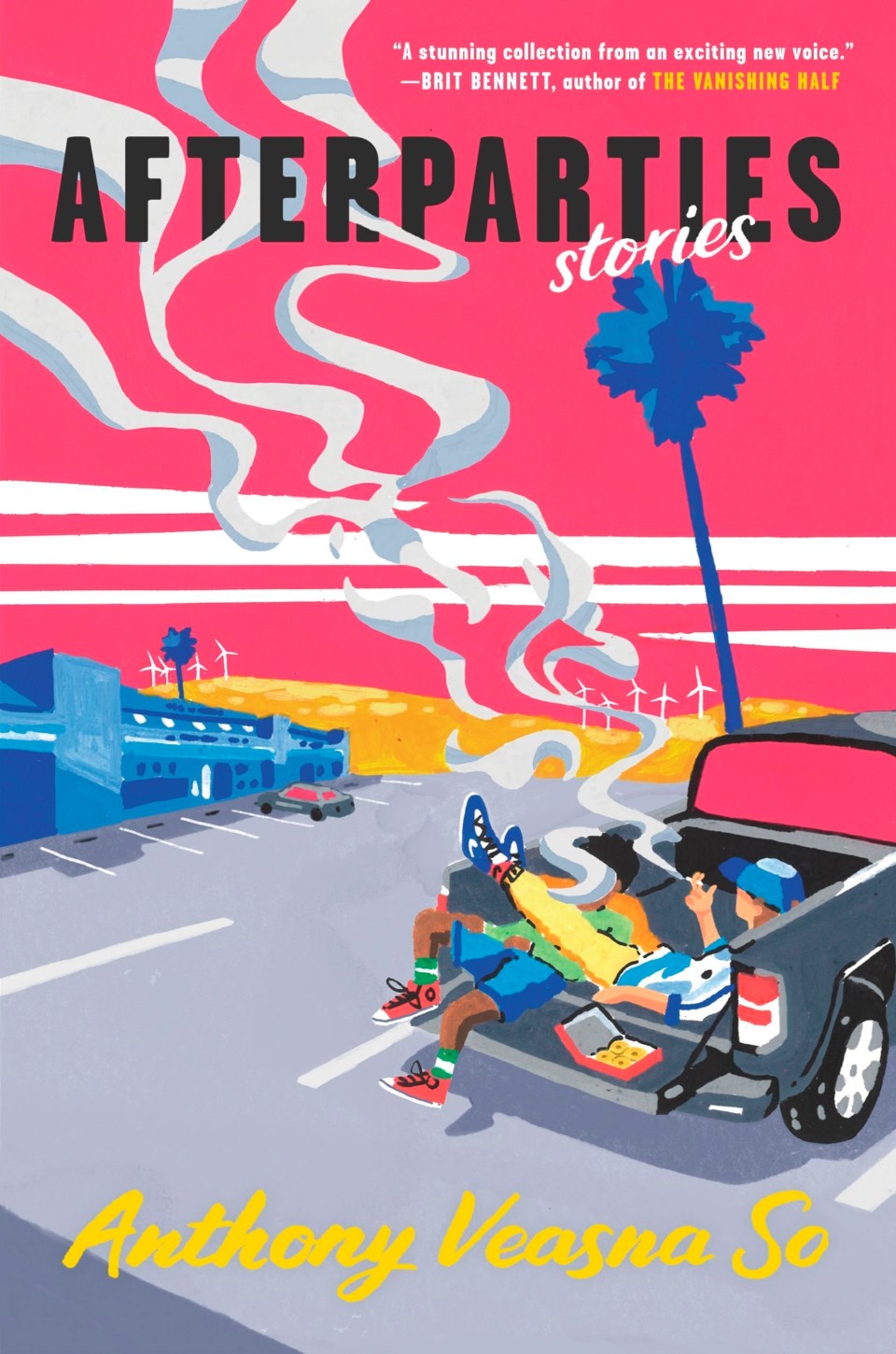

“Afterparties,” by Anthony Veasna So (Ecco)

In 1975, the Khmer Rouge seized power in Cambodia, establishing a regime whose fanatical policies led to the death of more than a quarter of the country’s population. That genocide is a recurring theme in Anthony Veasna So’s dazzling new story collection “Afterparties.”

So, who died of a drug overdose last December at age 28, was the son of Cambodian refugees. He grew up in California’s Central Valley, majored in art and literature at Stanford, and earned an MFA in fiction from the prestigious writing program at Syracuse.

When he died, he was on the verge of literary stardom, having secured a six-figure, two-book deal from Ecco. The first one, “Afterparties,” is an astonishing debut, crackling with energy, narrated in slangy vernacular, and written with attitude and style. The second book, a combination of fiction and nonfiction, is due out in 2023.

“As a kid, I heard traumatic stories of my family’s experience surviving... Pol Pot’s regime that somehow always landed on a joke,” he wrote in 2018, the year his rollicking short story “Superking Son Scores Again” appeared in the literary magazine n+1. Narrated in the first-person plural by “the young men of this Cambo hood,” it is about a grocery store owner who moonlights as a high school coach — “a regular Magic Johnson of badminton” — but can’t focus on the team because he is in trouble with loan sharks.

In “The Shop,” a busybody in the refugee community brings in a squad of Buddhist monks to restore the karma of a failing auto shop, offering unsolicited advice to the owner’s gay son: “Marry a girl because that is what you should do. I am not saying you cannot be gay. How hard is it to be normal and gay?”

In “Maly, Maly, Maly,” two cousins, Ves and Maly, get stoned and watch a porno film in their uncle’s video store before a party to celebrate the reincarnation of Maly’s mother in another cousin’s baby. In “The Monks” a young man goes on a retreat at a Buddhist temple to help his father’s spirit in the afterlife, gets high with a member of the religious order, and is amazed to discover that all the “praying songs” are actually Khmer covers of the Beatles.

In each of the nine stories, So lays out for inspection all the problems of his beloved community — from gambling and gossip to alcoholism and suicide — then embraces it all with love and compassion. It is a virtuosic performance.

Ann Levin, The Canadian Press