A new blood-clotting syndrome seen in a small minority of COVID-19 vaccine recipients continues to draw significant attention, but experts maintain the event is exceedingly rare — and treatable, in most cases.

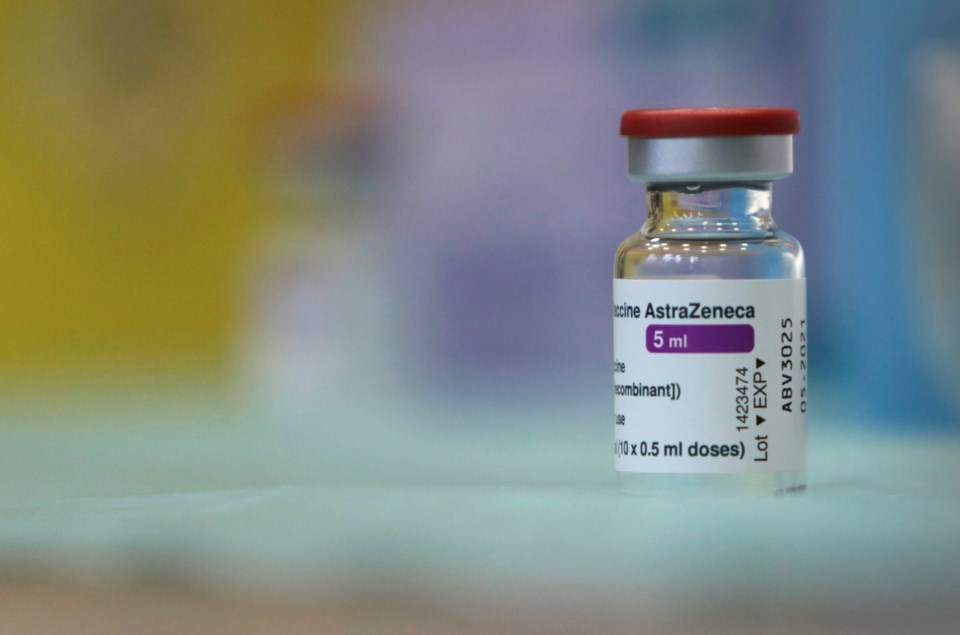

Vaccine-induced thrombotic thrombocytopenia, or VITT, has been identified in at least 12 Oxford-AstraZeneca recipients in Canada, and among those cases there have been three deaths.

Dr. Jeff Weitz, the executive director of the Thrombosis and Atherosclerosis Research Institute (TAARI) at McMaster University, said in an interview last week that doctors are learning more about VITT every day.

And that's good news for those worried about potentially developing the disorder, which has been associated with but not definitively linked to the viral vector shots from AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson.

"We now know how to diagnose this and we know how to treat it," Weitz said. "So even if you are one of those unfortunate, rare individuals — maybe four out of a million — who get it, we know what to do."

Most experts have maintained the benefits of vaccinations far outweigh the small risk of the clots, with Weitz noting that clots have been detected far more often in COVID-19 patients.

But some provinces are starting to move away from using AstraZeneca. Citing dwindling supply, Alberta announced Tuesday it would no longer administer first doses of the two-dose jab, and hours later Ontario said it is pausing first doses due to increased instances of the rare clotting disorder. Canada's increased supply of mRNA vaccines from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna means more Canadians are getting access to those shots.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said Tuesday that all of the authorized vaccines have been "deemed safe and effective by Health Canada."

Here's what we know about VITT:

HOW OFTEN DOES IT HAPPEN?

The risk of VITT has been estimated as anywhere from one case in 50,000 doses given, to one in 250,000.

Thrombosis expert Dr. Menaka Pai said last week that range is due to different reporting standards around the world, and numbers can change as more vaccines are administered globally.

"Every day we're giving more shots, and of course, doctors are surveilling for cases, so it's literally changing every hour," she said.

The National Advisory Committee on Immunization says the rate of VITT in Canada was closer to one per 100,000 as of April 28. More than 1.7 million doses of AstraZeneca were administered in Canada as of late last month. On Tuesday, Ontario said the risk in that province was closer to one in 60,000.

Meanwhile, 17 cases of VITT had been confirmed as of April 23 in the United States — out of more than eight-million doses of Johnson & Johnson's viral vector vaccine. AstraZeneca is not approved in the United States, and Johnson & Johnson, though authorized in Canada, has not yet been used here.

WHAT'S CAUSING VITT?

Pai said the disorder appears to be an immune response to viral vector vaccines. As antibodies are produced within four to 28 days of the jab, platelets somehow get "switched on" in a small number of people.

She said it's not clear why a minority of recipients are affected and others are not.

Previous blood clots or family history of clots don't appear to hold significance, Pai said, nor does being on the birth control pill — which carries its own clotting risk of about 5 in 10,000.

Gender also doesn't seem to indicate who's more susceptible to VITT, Pai added.

WHAT ARE THE SYMPTOMS TO WATCH FOR?

A number of wide-ranging symptoms could indicate VITT. Initially, NACI said to watch for signs between four and 20 days after receiving a viral vector vaccine, but recently extended that timeline to four to 28 days.

Symptoms include persistent and severe headache, difficulty moving parts of your body, seizures, blurred or double vision, shortness of breath, or back, chest or abdominal pain. Significant changes in a limb — swelling, redness, a pale appearance or cold feeling in an arm or leg — could also indicate clotting.

Clots typically appear in the head, lungs, legs or stomach, so symptoms associated with those body parts should not be ignored. But Weitz said some VITT clots have been seen in parts of the body not usually associated with clots, including the splanchnic veins that drain the liver, spleen and bowel.

The rare VITT clots have been seen almost exclusively after the first dose of a viral vector vaccine, but Pai noted one case was reported following a second dose in the United Kingdom. That person did not experience a clot after their first dose.

WHAT DO YOU DO IF YOU THINK YOU HAVE VITT?

Pai said people should seek medical care if symptoms emerge.

A primary care physician — a family doctor, walk-in clinic or telehealth practitioner — can offer guidance "if symptoms are manageable."

But if they appear more severe, head to an emergency room.

Like many other conditions, VITT appears to be easier to treat when caught early.

HOW IS IT DIAGNOSED?

A doctor would order a complete blood count (CBC) to determine whether a patient's platelets are low, sometimes followed by additional blood tests or imaging — an MRI, for example — to detect whether or not a clot has formed.

HOW IS IT TREATED?

Effective treatments are available, Pai said, "if started in a timely fashion," including special types of blood thinners and drugs that modulate the immune system.

She stressed that while rare, the clotting disorder has been serious and treatment may be intensive for some.

"It's not like you get a shot of something and go home," she said. "Generally it will involve hospitalization and some really thoughtful care by a number of different doctors."

Doctors are staying away from using the blood-thinner heparin on VITT cases, which seem to closely resemble another disorder called HIT, or heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.

While the mortality rate among the rare VITT cases worldwide seems to be around 20 per cent, Weitz said that number is expected to decrease.

"We're getting better at knowing what it is and how to treat it, diagnosing it earlier," he said. "But it's still not something you want to get."

This report by The Canadian Press was first published May 12, 2021.

Melissa Couto Zuber, The Canadian Press