LOS ANGELES (AP) — America slammed the door in the face of Black progress time after time, and time after time African Americans responded by thriving in a society of their own making.

When Black doctors were excluded from the American Medical Association, they formed the National Medical Association in 1895. Black colleges, businesses, social groups and even fashion shows grew as alternatives to whites-only institutions and activities.

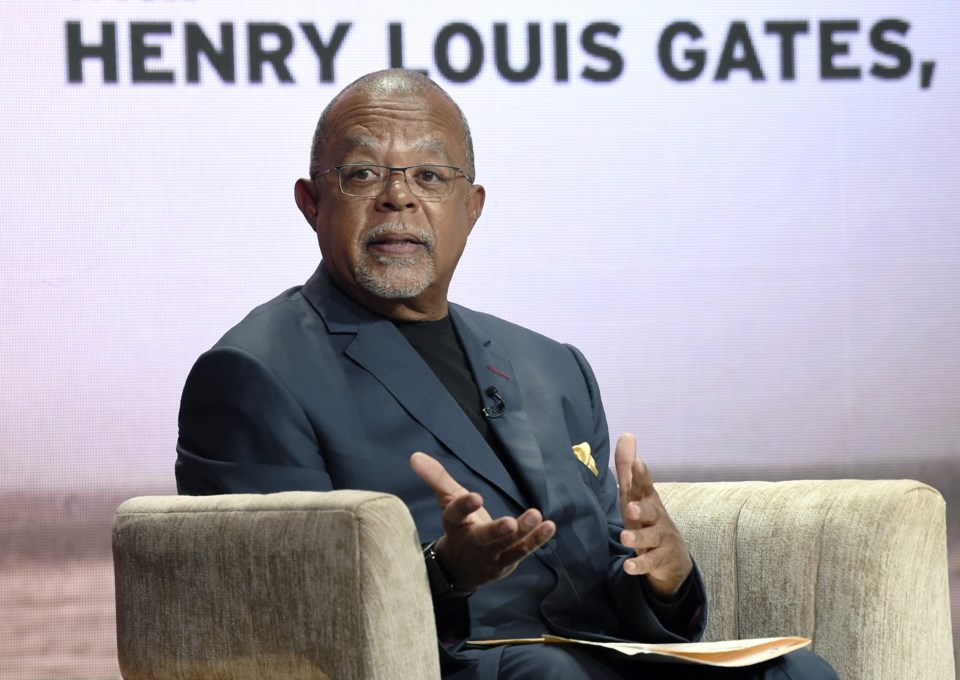

The result was a parallel “sepia world” in which Black lives and culture could flourish despite entrenched racism, says filmmaker and scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr., who celebrates a history of resilience in “Making Black America: Through the Grapevine.”

The four-part series debuting Tuesday on PBS (check local listings) and PBS online was produced, written and hosted by Gates, a steady chronicler of Black history and culture whose more than a dozen documentaries include 2021's Emmy-nominated “The Black Church: This is Our Story, This is Our Song." He's also the host and producer of PBS' “Finding Your Roots.”

“Making Black America” is infused with Gates' self-described optimism. But he considers it his “most political" series yet because it shows the “true complexity of the African American experience,” he said in an interview with The Associated Press.

“We need to have our self-image, our self-esteem affirmed, because so many actors in our society are trying to tear down our self-esteem, trying to tear down our belief in ourselves," he said.

Gates said the series is a rebuttal to what he calls the stereotype of a Black America consumed with white people and devoting all of its energy and imagination to fighting white supremacy.

“What you do with most of your imagination is you fall in love, you raise a family, you have children, you build social networks,” said the Harvard University professor. “This is a demonstration of Black agency, the way we created a world within a world.”

Gates compared the Black havens to those established by Jewish Americans and other ethnic groups when they were barred from employment, cultural institutions and other elements of U.S. society.

During a Q&A with TV critics, Gates delighted in pointing out that the “grapevine” in the series' title pre-dated the Motown hit song “I Heard it Through the Grapevine” by about two centuries: He said founding father John Adams wrote about the grapevine concept in 1775, and it was referred to by Booker T. Washington in 1901. Washington founded what is now Tuskegee University.

The vivid word broadly describes “the formal and informal networks which, for centuries, have connected Black Americans to each other through the underground, not just as a way of spreading the news, but ways of building and sustaining" Black communities, said Gates.

Shayla Harris, who produced and directed the series with Stacey L. Holman, said that the Black experience is often sorted into either “the struggle” or abundant creativity. But business drive is also a notable part, she said.

“The Negro Motorist Green-book, ” a 1936-67 guidebook to businesses that would serve Black travelers, is generally discussed in the context of the restrictions that people of color faced under Jim Crow segregation.

That ingenuity also was testament to the Black entrepreneurs who exemplified the saying that “Black people make a way out of no way,” Harris said. The guide was “a document of 7,000 Black businesses across the country, from restaurants to hotels to beachfronts and just any little stand that people could put together.” (The guide was central in the 2018 Oscar-winning interracial road trip movie “Green Book,” which won best picture and best supporting actor for Mahershala Ali.)

Other aspects of African American perseverance highlighted by the series and its creators:

—The barbershops and hair salons that serve as community centers. Gates said he still delights in going to the Nu Image Barbershop in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard's home town. The talk is about “what you're anxious about, your kids, what's in the news, of course. And you talk about LeBron (James) and Steph Curry and the Celtics. The full gamut of human emotions.”

— Excluded from professional, trade and even recreational associations, African Americans formed their own. In naming the groups, they used “national” in the titles as a “polite” way to signify the membership was Black, Gates said. That included the National Dental Association and the National Brotherhood of Skiers. (In 2008, the American Medical Association formally apologized for decades of racial discrimination.)

—The robust number of sororities, fraternities and fraternal orders that contribute to Black social life and networking. One had roots in today's Prince Hall Freemasonry. It began with a Massachusetts lodge initiated in 1775 by Masons from Ireland after Colonial whites rejected Hall and a handful of other Black men for membership.

—The innovative Black women who stood out in business. They included early 20th-century business mogul Madam C.J. Walker, inventor and philanthropist Annie Malone and Maggie L. Walker, who was among America's first female bankers and who focused on the needs of the working class. To see these women succeed despite a society “that's pushing against you and a society that's predominately male ... was enlightening, encouraging and just empowering,” Holman said.

—The Ebony magazine-sponsored Ebony Fashion Fair runway shows that countered the industry's overt discrimination by featuring Black models and designers for an audience that dressed for the occasion. The annual event, which was staged nationally and outside the U.S. for five decades, raised millions of dollars for charity.

Lynn Elber, The Associated Press