Counting the cost

The Gazette is looking at how residents are dealing with the rising costs of living in St. Albert. If you have a question on why life is so expensive, email [email protected] so it can be answered in a future story.

It’s March 2020. Alberta is in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, and thousands of people are out of work and at risk of poverty due to public health restrictions. Governments scramble to give out emergency funding, contributing to rapid inflation and more financial troubles.

Was there a better way? University of British Colombia economist Rashid Sumalia thinks so.

“If we had a basic universal income across the board … then the government would not have to do that,” said Sumalia, who holds the Canada Research Chair in interdisciplinary ocean and fisheries economics.

“We would already have an [economic] base everyone could live on.”

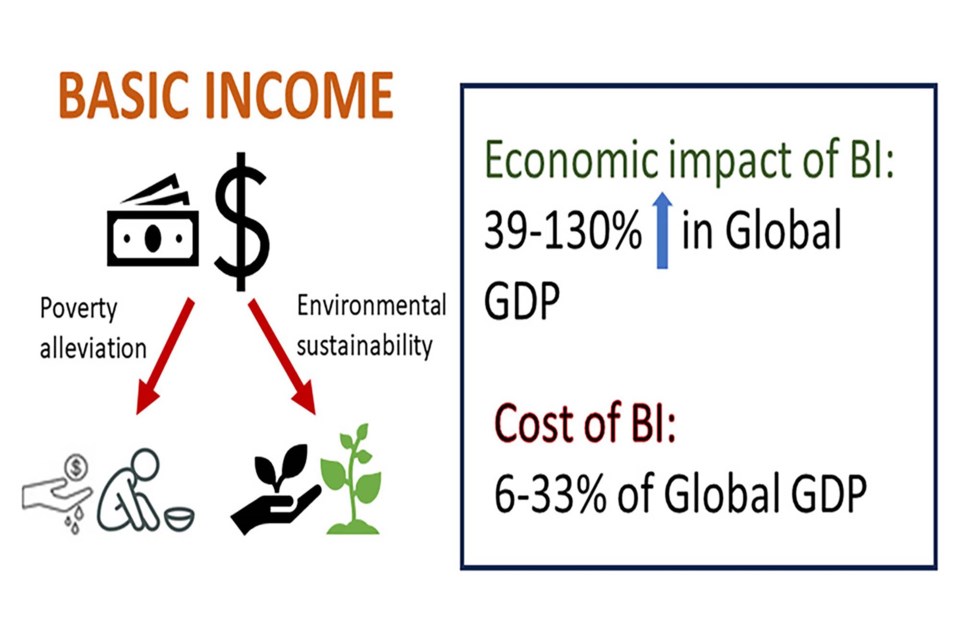

Sumalia is one of a growing number of advocates calling on Canada to implement basic income to fight poverty and deal with the rising cost of living. His team published a paper on the policy in Cell Reports Sustainability on June 7.

Canadians are also warming to the idea. A 2020 Angus Reid poll found that about 59 per cent of Canadians supported the idea of basic income, with 61 per cent saying it should be funded by taxes on the wealthy. Canada’s MPs and senators are even now debating bills to develop frameworks for basic income.

Cash safety net

Basic income is periodic cash payment unconditionally delivered to everyone regardless of income or employment, the Basic Income Earth Network reports. Advocates say such income can give people a secure financial platform to build on, make it easier to start new businesses, and life people out of poverty. The Canada Emergency Response Benefit ($500 a week for 28 weeks) was arguably an example of basic income.

Sumalia said basic income programs give people an economic cushion against shocks like a pandemic or disaster, reducing the need for emergency government support. This, in turn, reduces poverty and the social costs associated with it (which one study pegged at about $80 billion a year in Canada).

Many organizations have tested the idea of basic income over the years and found that it yields significant social and economic gains.

A 2023 study in Vancouver saw researchers give 50 homeless people $7,500 and tracked how they used it, for example. The researchers found that those who got the cash spent 99 fewer days homeless, saved more money, and did not spend more money on temptation goods like alcohol, resulting in a net $777 per person savings due to reduced time spent in shelters.

Ontario did a basic income study in 2017-2018 that saw about 2,000 people who earned less than $34,000 a year get about $1,400 a month. McMaster University researchers found that these people were healthier, more physically active, and more motivated and able to find a better paying job after getting this cash, with 68 per cent cutting back on use of food banks and 37 per cent reducing emergency room visits.

There can even be environmental benefits. Sumalia noted how one study in Indonesia found that basic income supports reduced deforestation by 30 per cent as residents no longer needed to chop down trees to make money.

The cost

Basic income programs aren’t cheap. A 2021 report by the Parliamentary Budget Officer found that a Canada-wide program modelled on the one done in Ontario would cost about $85 billion, but could cut poverty rates by roughly half. UBI Works (a think-tank promoting universal basic income in Canada) pegs the net cost of such a program at $51 billion once one accounts for the tax credits the program would replace.

Sumalia said some economists say basic income could discourage people from seeking work, but real-world evidence suggests otherwise. The Alaska Permanent Fund has been giving residents of that state basic income since 1982, and has had no impact on employment. The Parliamentary Budget Officer found that nationwide basic income would have “small” impacts on labour supply, with hours worked in Alberta falling by 0.7 per cent.

Sumalia said governments could fund basic income by eliminating environmentally harmful subsidies to fisheries and oil and gas and by taxing other environmental wrongs, such as carbon or plastic waste. A global carbon tax would generate some $2.3 trillion, for example, which was enough to provide basic income for everyone in Africa, Oceania, and South America combined.

“This is what I call saving two birds with one stone,” he said, as you reduce poverty while also addressing environmental crises.

Research by UBI Works suggests that a national basic income program of $1,500 per individual per month could be funded without affecting anyone who earns under $100,000 a year through taxes on banks, big business, and the rich.

Sumalia noted that the need for basic income should fall over time, as it helps more people find jobs and creates more economic activity. His team estimated that every dollar invested into basic income for people below the poverty line in North America would result in about $8 of economic activity. UBI Works estimates that universal basic income could add $80 billion to the national economy a year and eventually create more economic growth than it costs.

Sumalia said basic income pilots can be done at any level of government, even municipal, as was the case with Stockton, California. What’s needed now is people to call on leaders to do them.

“If enough people call for it, it will happen.”