The spring of 2003 was a time when cattle producers across Mountain View County and all of Alberta were “basically in survival mode,” recalls Ernie Israelson.

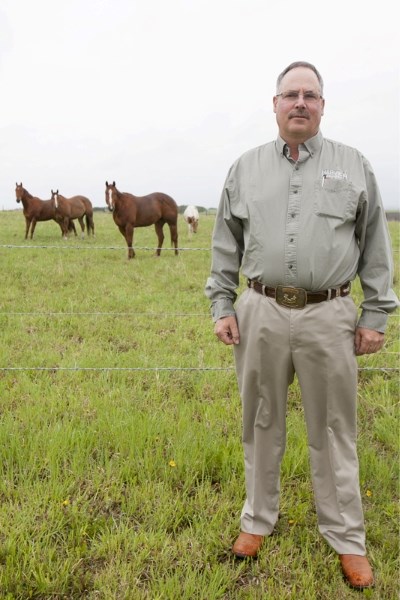

A cattle producer with an operation just west of Didsbury and a former director with the Alberta Beef Producers, Israelson looks back over the decade since the discovery of a case of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) in Alberta closed international borders to Canadian beef and describes those years as a time when cattle farmers were in uncharted territory.

“We were a boat paddling down a river that hadn't been travelled before,” said Israelson.

It was May of 2003 when the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) confirmed an Alberta cow had tested positive for BSE, an affliction that also goes by the moniker mad cow disease and breaks down the brain and spinal cord in cattle.

Upon learning of the discovery, numerous countries around the world, including the U.S., Canada's largest trading partner, and Japan, closed their borders to Canadian cattle and beef.

Israelson said the repercussions from those closures were swift and brutal for Alberta producers.

“On one day, your cattle are worth full price and the next day, you couldn't receive half the value for them. It was just that devastating, that quick,” he said, adding since Canada was a net exporter of beef, having nowhere to send product meant herd numbers grew and grew for roughly three years.

“When you wake up one morning and all your export markets are closed, we did have an excess of product and there's no way we were going to be able to consume that product domestically.”

Since 1993, 17 cases of BSE have been confirmed in Canada, with the majority of cases being discovered between 2003 and 2008, and the Alberta cattle industry, which oversees roughly six million animals, suffered millions of dollars in losses as a result of the disease.

“It's almost incomprehensible that 17 animals that came down with the disease could inflict that much damage percentage wise on such a large population of animals,” Israelson said.

Wilhelm Vohs, who owns and operates Valley of Hope Farms west of Spruce View in Red Deer County, faced difficult times along with many of the other cattle producers in the province in 2003.

But the BSE crisis really hit home for him in 2005 when one of his cows suffered a broken back in a scuffle with another cow over feed.

Vohs said he euthanized the cow and, as a precaution, had the animal tested for BSE.

When the test came back positive for the disease, Vohs was shocked.

“I just about fell over,” he said, adding he and federal investigators still aren't sure how the cow became the fourth animal to contract BSE in Canada since 2003, although he theorizes it may have come from a mineral supplement.

The repercussions to Vohs' farm were severe.

The CFIA took roughly 35 other cows from his operation for testing, including animals born the same year as the cow that tested positive—as well as the year before and the year after— and although he received what he considers fair financial compensation, the loss of his “best producing cows” hurt breeding activities at the farm.

“Those were my prime cows and I didn't really want to sell them,” he said, adding none of them tested positive for BSE. “So that sets you back breeding.”

In the weeks and months that followed, Vohs was able to sell some bulls at reduced prices but overall, his operation's business began to suffer.

“Things got tougher after that,” he said. “Even though it's not a genetic thing, people kind of shy away. You're the guy with the cow.”

The media also became aware that it was one of his cows found to have BSE and within four days of the discovery, Vohs was fielding calls from reporters and addressed 40 of them in a press conference he described as overwhelming.

“It was a stressful time, for sure.”

Ian Harvie, who was reeve of Mountain View County in 2003 and is also a cattle producer living southwest of Olds, said at the height of the crisis, straight cow-calf producers experienced a decrease of 60 to 70 per cent devaluation of their base herd and his own bull sales were typically down in price by about $2,500 a head.

The county, he added, tried to help where it could by setting up a program where county residents could pay taxes in increments, partly to help producers weather the storm, and no new tax increases were introduced at the time.

When asked how long it took the industry to recover in the county, Harvie said repercussions are still being felt today.

“I don't know if it ever has recovered fully,” he said, adding the crisis led to the “demise” of many operations in the region and some countries have only recently started reopening their borders to Canadian beef.

Israelson was equally pessimistic about the rate of recovery.

“We still haven't returned to full normal relationships in export trade because Japan still won't take over-30-month cattle and even a country like Mexico, which is our second-largest trading partner, still won't take over-30-month cattle.”

And along with the crisis forcing some people out of the industry, he added, BSE and its effect on Alberta cattle producers discouraged “new players from coming into the industry.”

“There's been very little rejuvenation with new people going into the industry.”