In 2020, with the COVID-19 pandemic taking precedence over other public health issues, Alberta paused its reporting of West Nile virus temperature maps. Three years later, it's still unclear whether that part of Alberta's West Nile surveillance program will ever start back up.

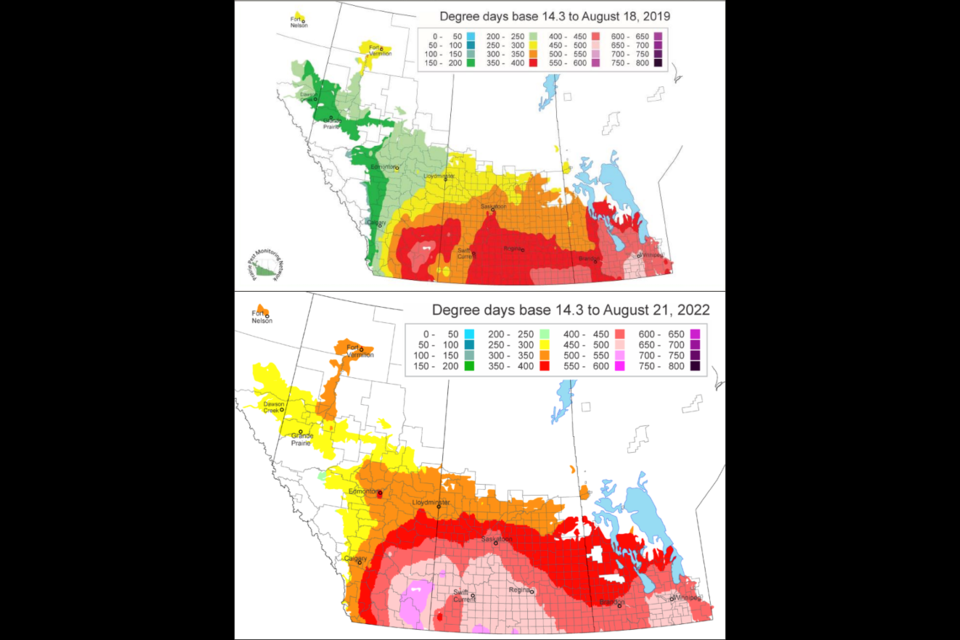

Mosquito-borne disease outbreaks are largely driven by weather patterns. The West Nile virus degree day maps are one tool public health authorities use to predict where and how severe the risk of infection will be by comparing daily average temperatures against the temperature mosquitoes that carry the virus need to reproduce.

"Until 2019, Alberta Health received and posted West Nile virus degree day maps with permission from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC). Between 2020 and 2022, this work was stopped at Alberta Health due to the pandemic priorities," said a member of Alberta's Open Government data team.

The maps were produced by the Prairie Pest Monitoring Network with support from AAFC. The program was discontinued this year, AAFC said in an e-mail.

Alberta Health Services has reported nine confirmed cases of West Nile virus this year, including two in Edmonton. Until recently, northern parts of the province were protected from the Culex mosquitoes that carry West Nile virus by its moderate climate. Now they are here and have quickly become entrenched.

"In 2020, we verified that (Culex pipiens) had showed up in Edmonton," said Mike Jenkins, pest management coordinator with the City of Edmonton.

"Almost as soon as it showed up, it suddenly became well-established in all of the environments around the city, and are well-represented in our mosquito population dynamics," he said.

Researchers predicted that climate change would cause a range expansion for the disease-vector mosquitoes, and the prairie provinces might see this shift between 2020 and 2080. Jenkins said he was surprised to find the Culex pipiens "at the earliest dates from those climate models."

"We were kind of expecting that they were going to show up. And so we were looking for them. But we didn't really expect them to show up that quickly or become as established as they have been," he said.

Unlike many other mosquitoes in the region, Culex pipiens take advantage of container habitats like old tires, bird baths, eaves troughs, or storm drains and "lay a raft of eggs on the surface of the water, which hatch almost immediately, and start their development there," Jenkins said.

These environments are much more difficult to treat than the sloughs and ponds where other species lay their eggs, and the city is exploring different mosquito control products better suited to the resilient pipiens.

In most communities north of Edmonton, this type of detailed mosquito monitoring and treatment isn't available. Instead, the Culex pipiens expansion is tracked as cases of West Nile virus show up in humans and large animals.

"Each year, Alberta Health’s conducts passive surveillance for West Nile virus in humans through the Alberta Precision Public Health Laboratory and Canadian Blood Services. Veterinarians and animal health laboratories report cases of West Nile Virus identified in horses," Alberta Health said in an e-mailed statement.

"West Nile Virus is considered endemic in Alberta. Human case numbers are expected to occur each year and the numbers can and will vary."