PORTLAND, Maine — There once was a tune that tickled the Internet's fancy/When TikTok revived the humble sea shanty/The views came fast, the fad could last/Go, read about it go:

___

People are stuck at home, toiling away, getting bored, going stir crazy.

Cooped-up sailors who felt the same way on long ocean journeys broke up the tedium with work songs called sea shanties.

It only makes sense, then, that shanties have come full circle with a moment of unprecedented popularity during the pandemic.

“Times are tough. If we can sing, it’ll help us get through it, just like sailors did on the tall ships,” said Bennett Konesni, of Belfast, Maine, who started singing sea shanties aboard a schooner in Penobscot Bay and performs several times a week with the Mighty Work Song Community Chorus.

TikTok helped sea shanties surge into the mainstream.

The app has a duet feature that lets people create a 60-second song and then allows others to add their voices.

People began using the feature to record sea shanties, and shantying quickly became a mainstream thing, starting last month. The ShantyTok movement has even contributed to a rendition by the Longest Johns of the centuries old “Wellerman” sailing into the United Kingdom's Top 40 chart. Another version by Nathan Evans with a driving beat reached No. 2 at midweek.

The sudden popularity isn’t so hard to fathom. After all, people are craving interaction during the pandemic, and shanties are group efforts that don’t require great singing skills — though some of the TikToks are quite sophisticated and elaborate.

___

Long live the work song’s run/To bring us a sense of glee and fun/One day, when the pandemic is done/Back to the office we’ll go

___

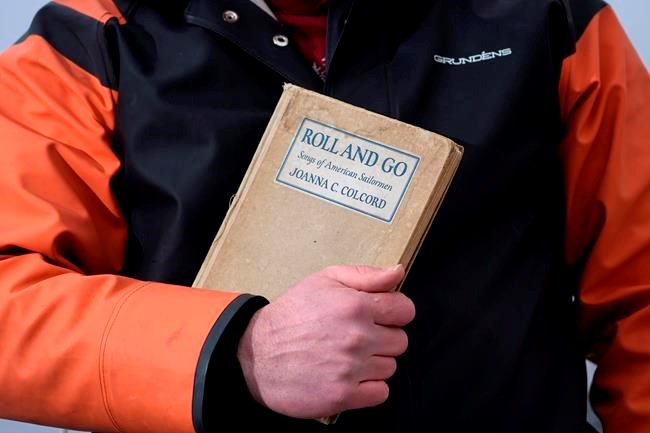

Shanties and sea songs are lumped together in the trend, but true shanties were work songs. Sailors of yore sang to pass the time and to

They generally consist of a chorus — in “Wellerman,” it’s about a ship loaded with “sugar, tea and rum” — that’s easy to memorize. There might be formal lyrics, or participants might choose to ad lib, with others joining for the chorus, said Matthew Baya, a radio show host from Williamstown, Massachusetts.

The shanties helped sailors defuse tension and remain sane amid the cruelty of isolation and cramped quarters. Shanties sometimes involved good-natured insults at skippers or the shipping companies that employed them.

Vocal chops are a bonus, but not a necessity.

“Not all sailors kept perfect pitch. They weren’t in that job for their musical talent,” Baya said. “You’ll get some people who are really talented, and other people who’re just having fun but may not hit all of the right notes.”

Many people who sing sea shanties at local festivals in Mystic, Connecticut; Portsmouth, New Hampshire; Plymouth, Massachusetts, and other seaport locations across the U.S. are thrilled by the sudden attention. Shanties are even more popular in some parts of Europe.

“If people are having fun singing, that’s got to be good,” said Baya, one of the hosts of the “Saturday Morning Coffee House” on WERU-FM in Blue Hill, Maine. His show often includes a shanty or two.

___

Many workers are stuck inside and alone/A sense of whimsy can throw them a bone/Because of that, the shanty trend has shone/So sing, sing as you go

___

Shanties tend to be associated with England, which ruled the seas in the 18th and 19th centuries. But they’re sung from Maine, where English colonists began a shipbuilding tradition, to Massachusetts, home of the nation’s whaling fleet, down to Alabama's Mobile Bay, the Caribbean and all the way around the world, Konesni said.

They’re work songs like the ones sung by enslaved people harvesting crops in the South, miners chipping away deep underground and loggers felling trees in the woods, all of which are seeing renewed attention thanks to shanties, said Konesni, who’s a cultural ambassador for the State Department and has performed shanties around the world.

The trend is a refreshing one in a world that has become accustomed to people performing on a stage for a crowd, Konesni said.

Shanties are different because they’re participatory. The audience is encouraged to boisterously sing along.

“It’s got a depth, history and singability that a lot of pop songs don’t,” he said.

Geoff Kaufman, who made a living singing sea shanties and directed the Sea Music Festival at the Mystic Seaport in Connecticut, said he’s amused and intrigued by the sudden fascination with shanties.

He loves the idea of a new generation lifting their voices.

“I hope it brings more young people into the fold,” he said.

___

Long live the work song’s run/To bring us a sense of glee and fun/One day, when the pandemic is done/Back to the office we’ll go

___

Associated Press writer Mallika Sen contributed to this report from Los Angeles.

David Sharp, The Associated Press