What would Joan think?

Reading the newly released “Notes to John,” it’s hard not to wonder how the late author Joan Didion would feel about having her personal notes from a series of painful therapy sessions converted into a book after her death.

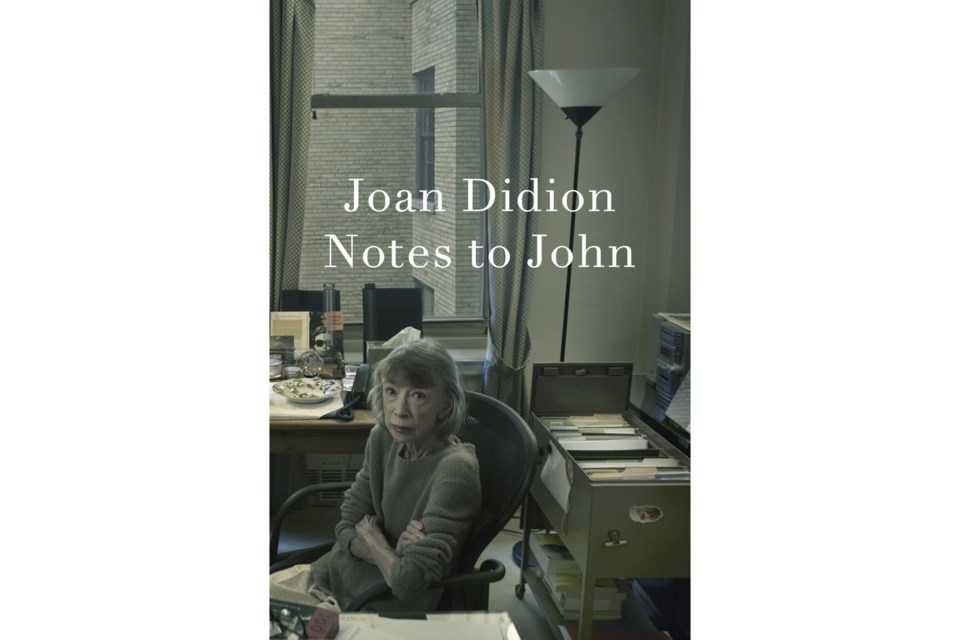

Discovered in a small filing cabinet in Didion’s office after she died in 2021 at age 87, the 150 loose pages formed a kind of journal she kept for her husband, writer John Gregory Dunne, about her meetings starting in late 1999 with psychiatrist Roger MacKinnon. The writer of such cult favorites as “The Book of Common Prayer” (1977) and “The White Album” (1979) was an assiduous notetaker and recordkeeper who explained her lifelong compulsion to write things down in her well-known essay, “On Keeping a Notebook,” to remember what certain moments had meant to her.

Still, the pages weren’t exactly a secret. They were included in papers that were placed by Didion’s heirs, her late brother’s children, without restrictions on access in the Didion/Dunne archive at the New York Public Library.

Much of the writings in the book released by Knopf center on the couple’s adult daughter, Quintana Roo Dunne, who was adopted as a baby and named after a Mexican territory that later became a state.

In the notes to Dunne, the famously guarded Didion details her worries and guilt about Quintana’s chronic alcoholism more openly than she did in the books she later wrote on that painful period.

“The Year of Magical Thinking” (2005) focused on Dunne’s fatal heart attack in 2003, and “Blue Nights” (2011) mourned her death just two years later at age 39 from acute pancreatitis.

“He wanted to know how old Quintana was when we got her, the details of the adoption,” Didion writes to Dunne about one session with MacKinnon. “We talked at some length about that, and I said I had always been afraid we would lose her. Whale watching. The hypothetical rattlesnake in the ivy on Franklin Avenue.’

Some of the most poignant passages are about the numerous dreams she described to the psychiatrist about her daughter’s addiction.

The hopelessness and vulnerability she acknowledges belie Didion’s cool and controlled public image.

“I told him about the dream I had this week in which Quintana and I were sharing a room and every time I woke during the night she wasn’t in her bed, she was sitting by the window and she was getting drunker and drunker,” Didion writes. “And there was nothing I could do about it. She couldn’t see me watching her.”

___

AP book reviews: https://apnews.com/hub/book-reviews

Anita Snow, The Associated Press