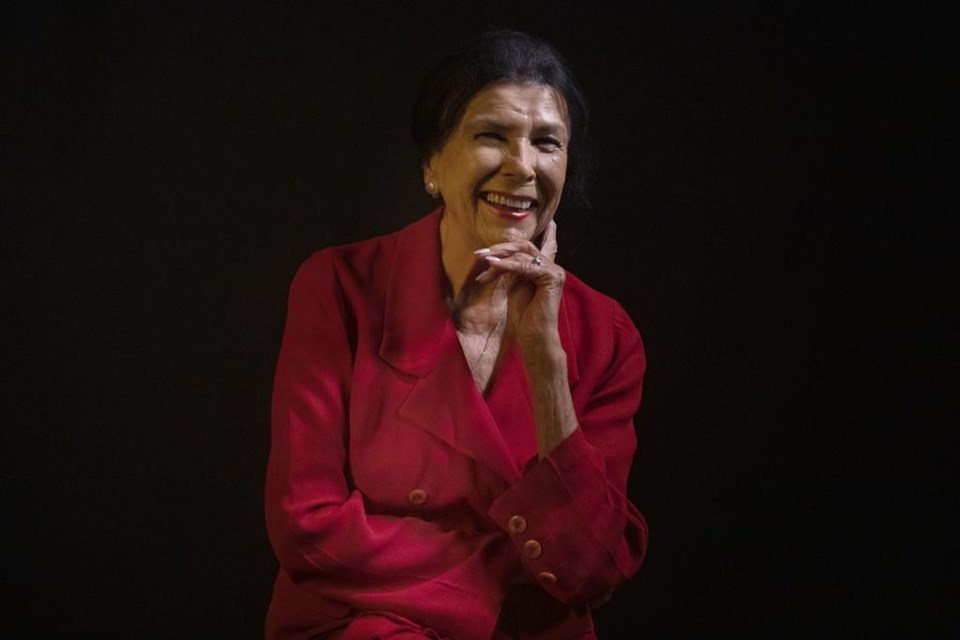

TORONTO — Documentary filmmaker Alanis Obomsawin had just wrapped shooting a beautiful sunrise for her newest film when word arrived that she won the $100,000 Glenn Gould Prize for her lifetime contribution to the arts.

The 88-year-old member of the Abenaki Nation said being selected by an international jury of her peers for her dedication to chronicling the lives and concerns of First Nations people was a powerful moment. It gave her further hope that a new era of possibilities is dawning for Indigenous creators.

"I feel very confident in the future," she said Thursday while on a short break from her latest untitled production in Odanak, Que., an Abenaki First Nations reserve.

"The energy and the interest for Indigenous people is something I've never seen as high as it is now. And when I say everything is possible, I really mean it. I think we are going to a place where we never have been before."

Obomsawin has spent decades illuminating the experiences of Indigenous people across the country and beyond.

She started her career as a singer-songwriter in the 1960s, releasing her only album "Bush Lady" several decades later. Her work extends into the visual arts, with engravings and prints that explore similar themes to her films, including how historical events influence dreams and memory.

But much of her time has been spent at the National Film Board where she directed landmark documentaries for more than half a century, including "Incident at Restigouche," which shed light on police raids at a Mi'kmaq reserve, and "Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance," about the 1990 Oka Crisis.

Many of those films were a struggle to make at the time, but Obomsawin said organizations that support the arts are starting to change their ways.

"There's a welcome feeling in all these institutions, which was not necessarily there before," she said.

Established in 1987, the Glenn Gould Prize is awarded in honour of the acclaimed Canadian piano virtuoso, who died in 1982 at age 50 after suffering a stroke.

The prize, which is handed out every other year, has been awarded to late U.S. opera singer Jessye Norman, U.S. composer Philip Glass, Canadian theatre icon Robert Lepage and late Canadian poet/songwriter Leonard Cohen.

Grammy-winning musician and U.S. visual artist Laurie Anderson was the chairwoman of this year's international jury.

The other jury members span an array of creative disciplines, including Indian pianist Surojeet Chatterji, U.K. author Neil Gaiman, French designer Philippe Starck and Canadian actress Tatiana Maslany.

"(Obomsawin) embodies so much, a history and a future that feels lasting and important," Maslany said in a phone interview shortly after the prize was announced.

"She is so incredibly prolific and inexhaustible, she's in her late 80s... that's kind of remarkable for anyone to have that continual drive to tell their story and the stories of people. It's really inspiring."

Maslany recognized that prizes like this help elevate influential artists into the wider culture, and have been a compass of sorts to finding other less mainstream artists such as Maliseet singer Jeremy Dutcher, whom she discovered after he won the 2018 Polaris Music Prize.

"I was part of a film where we weren't necessarily centring Indigenous voices in any way," she said, referring to the 2016 film "Two Lovers and a Bear," shot in Iqaluit with a largely white cast of lead actors.

"So I'm very aware of how forgotten all those communities are. This gesture as a Canadian felt really important and long overdue."

As part of the prize, Obomsawin will choose a young artist or ensemble to receive the $15,000 City of Toronto Glenn Gould Protege Prize later this year.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published October 15, 2020.

David Friend, The Canadian Press