Rulon Gardner is living a quiet life, just the way he likes it.

He is 48 now, sells insurance and has a second job coaching wrestling at a Salt Lake City-area high school.

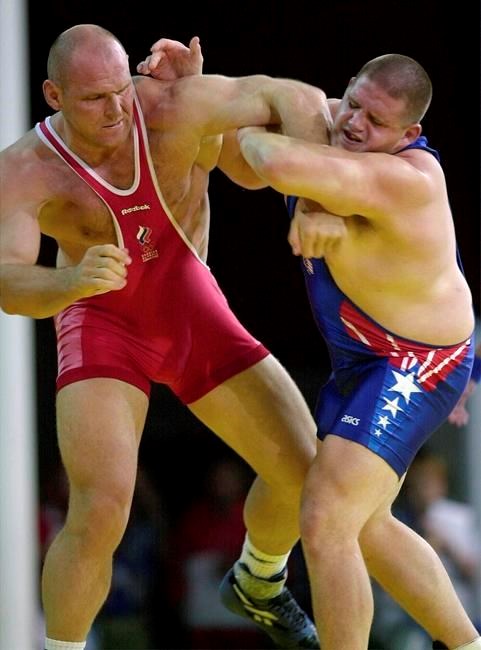

It’s been 20 years since Gardner, a 2,000-to-1 underdog, beat three-time gold

His story didn't end there. Not by a long shot.

“My life,” he said in an interview, “has been a roller coaster.”

Winning gold was the start of a ride that began with the farm boy from Wyoming becoming an instant celebrity.

Just as he was easing back into his old life, he was the talk of the nation again when a harrowing snowmobiling outing left him with frostbite so severe it cost him a toe and all feeling in his feet. From there followed a motorcycle accident, an improbable comeback to take bronze in 2004, a plane crash, weighing in topless at 474 pounds on “The Biggest Loser” reality show and losing millions after getting taken in a real estate scam.

All that and more are chronicled in “RULON,” a documentary coming soon on the Olympic Channel.

Adam Irving, the director, said he was 18 at the time of the 2000 Olympics and unfamiliar with Gardner's story until he was approached about making the film.

“I had to look up ‘Rulon Gardner,’” Irving said. "Within 10 seconds of reading his Wikipedia page, I knew that it would be hard to mess up the film because his life story has so many dramatic moments you couldn’t make that stuff up.”

Karelin is compared to fictional superhuman Russian boxer Ivan Drago from “Rocky IV." Before meeting Gardner, the wrestler known as the “Russian Bear" won 887 of 888 matches and had not surrendered a point in six years or been beaten in 14. His patented move was the the terrifying reverse body lift in which he would throw his opponent feet first over his head.

Gardner had never finished higher than fifth in an international competition and struggled to get past his semifinal opponent in Sydney. The media portrayed the gold-medal match as a coronation for Karelin as he headed into retirement.

“When I walked out there, yeah, I was nervous,” Gardner said two decades later. “Did I believe in myself? Yeah. Did I think I could beat him? No. Did I have a chance? 100

The film captures the rapture of Gardner beating the world’s greatest wrestler, but this isn’t just an underdog story. Improbable Olympic glory defines Gardner, but so do the near-death experiences and other unfortunate events that come his way.

Gardner is the narrator, with comments from his former coach and journalists who covered his story. Some of the archived video, particularly footage of the treatment for his frostbite, had never been shown before.

The opening shots have Gardner carrying a calf and knocking around a friend's dairy farm near Logan, Utah. Gardner's family no longer has the Wyoming dairy farm where he grew up.

For the youngest of Reed and Virginia Gardner's nine children, childhood was all about hard work and chores. Among classmates he was an object of ridicule for being overweight and having a learning disability that put him at a fifth-grade reading level when he graduated from high school. He had a contentious relationship with his dad. His mother was a buffer between the two and an enduring source of love and support.

Wrestling provided escape from the grind of farm life, yet he didn't make his high school's varsity team until his senior year. He left the University of Nebraska with a hard-earned degree in physical education and began competing internationally in 1996.

The “Miracle on the Mat” turned him into an American hero. He made the rounds on the talk-show circuit, rubbed elbows with A-listers and amassed large sums of money thanks to endorsement deals.

Bad luck and bad decision-making ensued, never more than in 2002 when he got separated from his snowmobiling party in the Wyoming wilderness. He rode aimlessly as darkness fell, ended up in a shallow river and trudged through snow to a stand of trees. Wet and with no blankets or food, he spent the night in sub-zero temperatures. Searchers found him the next morning.

Perhaps his lowest point came when he filed for bankruptcy in 2012. A deal to develop a hot springs went bad and Gardner was stuck owing almost $3 million. He had to sell his gold and bronze medals, which he has since recouped, and auctioned off other memorabilia.

Not addressed in the documentary were Gardner's Mormon faith and his four failed marriages.

“Those are kind of private,” Gardner said. “There are some things you don’t bring up.”

His lifelong battle with his weight was not off limits. In fact, it's an underlying theme, and a scene of him in his kitchen talking to his tiny dog is particularly moving. He wouldn't disclose his weight during a recent interview, but the math indicates he’s over 400.

He said he’s lost 30 pounds in the last month, thanks to working with a coach and cutting refined sugars and processed food from his diet. He has said his goal is to get back close to his wrestling weight of 265.

“I have well over 150 pounds more to lose,” he said.

Gardner sold medical equipment before joining an insurance agency in Payson, Utah, two years ago. About the same time he was hired as head wrestling coach at Herriman (Utah) High School.

It strikes him a bit funny, after all he's gone through, that he's happily settled into an insurance career.

“It's all about mitigating risk, making better choices,” he said. “People ask me, ‘What do you know about safety?’ I'm like, ‘Let me tell you some stories.’"

___

More AP sports: https://apnews.com/apf-sports and https://twitter.com/AP_Sports

Eric Olson, The Associated Press