NEW YORK (AP) — Igor Levit arrives at Carnegie Hall changed by the pandemic.

“We are not on our way back to normal. I don’t think we should be on our way back to anything. There is no normal out there," the 35-year-old pianist says, citing uncertainty around the pandemic, the war in Ukraine, energy shortages and climate change. "It’s not like we’re going through normal. So I find traveling and playing both very intense and yet incredibly rewarding. I cherish every concert I play in a way maybe I was a little bit less aware of pre-pandemic.”

At Carnegie on Tuesday night, he plays Shostakovich’s 24 “Preludes and Fugues,” part of a quick U.S. tour that takes him to the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., on Thursday and Clayton State University in Morrow, Georgia, on Sunday.

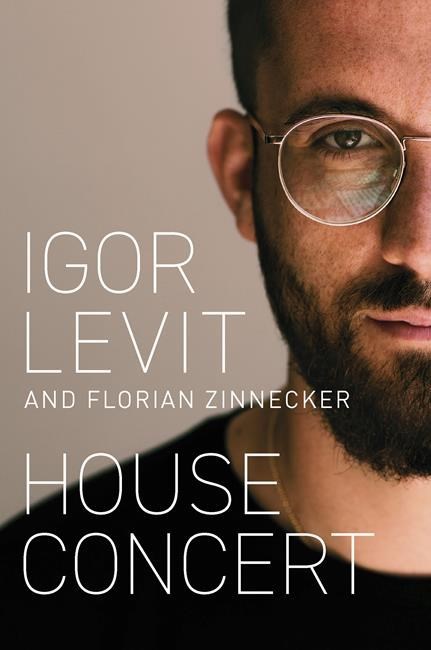

His new recording “Tristan” was released by Sony Classical on Sept. 9 and his book “House Concert,” written with Florian Zinnecker, is being published in English by Polity in January.

Levit’s playing has a bravura intensity and an elegance, connecting emotionally and intellectually. Outspoken on social media, he is self-described as “Citizen. European. Pianist.”

On March 10, 2020, his 33rd birthday, he played two Beethoven piano concertos at Hamburg’s Elbphilharmonie. Two days later, after COVID-19 shutdowns began, he started what turned into 52 streamed concerts from his Berlin apartment. He did not resume public performances before an audience until the spring of 2021.

“I had about 2.3 million people in my living room,” he said. “It was not like I was playing for my phone. I was playing for real people. Emotionally there was no difference. So I knew that there are people and I better treat them with respect and I better try hard and I better play well, because these people gift me with their time, which is the most precious thing they have.”

Levit called his first piano “Lulu” after the title character in Berg’s opera and his second “Monk” after Thelonious. He now uses a 1923 Steinway once owned by the Swiss pianist Edwin Fischer.

He most memorably performed Erik Satie’s “Vexations” on May 30, 2020, a theme and two variations repeated 840 times and stretching for about 20 hours. He paused only for only short breaks for water and bathroom trips, and about 800,000 people listened.

“There was actually only one moment where I thought, why am I doing this? Because I was playing for 4 hours and there was still this pile of papers. I thought, like, there was no progress being made at all. But that lasted for 20, 25 minutes,” he recalled. “It was big fun to do. Then the following day, I was totally high. It was fantastic. I would better not recapitulate how much I drank that day. And then the day after, that’s when I kind of crashed and felt a little drained.”

His only uncomfortable performances during the shutdown were in empty concert halls for a camera.

“These spaces were not meant for that. It feels like a lie,” he said. “That’s not what it should be about.”

“Tristan,” largely recorded in the Berlin Philharmonic’s Chamber Music Hall in September 2020, features Zoltán Kocsis’ arrangement of the opera’s prelude, a follow-up to Liszt’s arrangement of the “Liebestod (Love death)” featured on Levit’s 2018 recording “Life.” The two-CD set, released by Sony Classical on Sept. 9, opens with Liszt’s “Liebestraum (Love dream) No. 3″ and is followed by Hans Werner Henze’s nearly 50-minute “Tristan,” preludes for piano, electronic tapes and orchestra. The second disc opens with the Wagner transcription and includes Ronald Stevenson’s arrangement of the adagio from Mahler’s 10th Symphony and Liszt’s “Harmonies du Soir,” his Transcendental Étude No. 11.

After appearing in Europe from December through February, Levit goes to Boston, La Jolla, California, and Los Angeles in March, then returns to Europe briefly before three concerts in Pittsburgh in May followed by a two-week residency in San Francisco.

“I just want to play the music I want to play,” he said. “And very often I find myself having the desire to play music which was not written for the piano. But then my desire to play is way greater than the fact that it hasn’t been written for the piano. So in the end I just make it happen, period, be it Wagner, be it Mahler, be it whatever comes into my mind.”

When Levit first considers a work he never has played before, he thinks his way through before putting fingers to keys.

“I gives me the chance to know the piece before I touch it, before I touch the piano,” he said. “I start imagining how it could sound like, what it should sound like, what I want it to sound like. It’s the most joyful thing to do for me.”

His book recounts his youth through the pandemic. His family left Russia when he was young and moved to Hanover, Germany.

“There’s a lot of pain because what sounds like an anecdote to you and to the reader, well, let me tell you the fact that a 9-year-old child had to make phone calls for his parents, is very painful for the parents, and we should never leave that out of our perspective,” he said.

“There’s beauty to it and there’s pain to it. And I think that every child who grew up as a migrant and in a new country has very, very similar experiences, seeing your parents struggle, seeing your classmates not really accepting you. Thinking back includes beauty and mostly, let’s face it, pain and in a way sadness.”

Ronald Blum, The Associated Press