TORONTO — Many artists are celebrated as trailblazers, but friends of folk singer-songwriter Curtis Jonnie, better known as Shingoose, say he leaves behind a legacy that set the course for generations of Indigenous musicians.

The performer died on Tuesday at 74 after recently testing positive for COVID-19, his daughter, Nahanni Shingoose-Cagal, confirmed. She said he was living in a Winnipeg care home after a stroke in 2012.

Whether it was his historic role in pressuring the Juno Awards to finally to establish a category for Indigenous music in the 1990s, or his bold foundation of his own Indigenous record label in the 1970s, some say the musician was a “visionary” ahead of his time.

“He paved the way for so many,” Shingoose-Cagal said in an interview from her home in Hamilton.

“Through his pain and life experiences, he's made such a huge contribution.”

Jonnie, who was Ojibway from Roseau River Anishinaabe First Nation, was a residential school and '60s Scoop survivor who, at age four, was adopted by a Mennonite family. They taught him to speak German instead of the Anishnaabomowin language of his mother.

As a teenager, he was sent to a Nebraska boarding school where he joined the choir and eventually picked up an interest in folk music.

The timing was right, as the 1960s folk scene was bustling with names like Gordon Lightfoot and Buffy Sainte-Marie gracing stages across North America. Jonnie was mostly interested in covers of more popular artists, partly because they’d guarantee gigs.

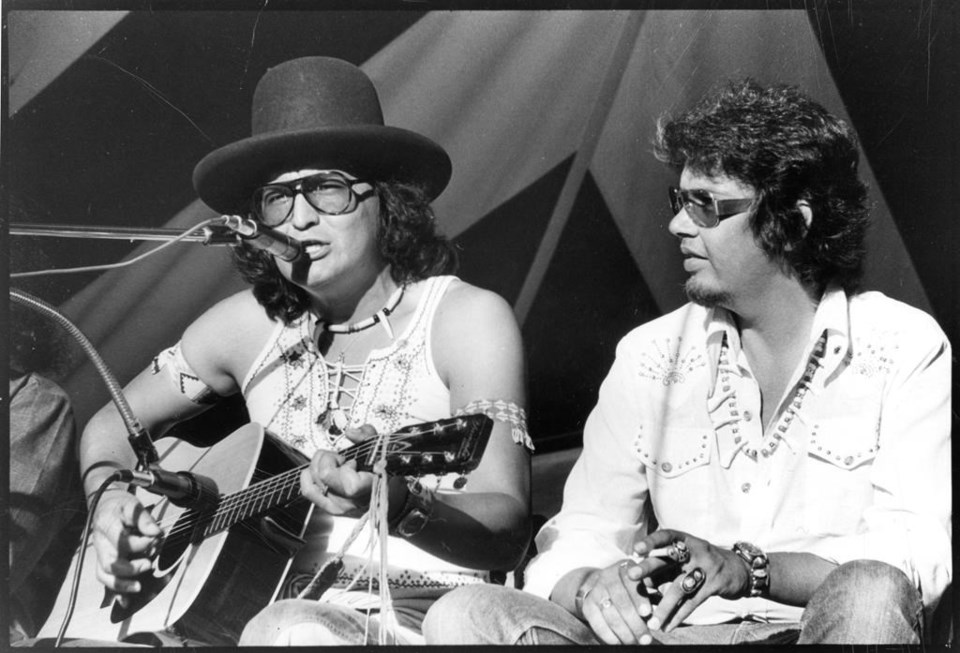

One of those shows was at the Mariposa Folk Festival, still held on Toronto's Centre Island, where his performance on the "Native stage" drew the attention of Duke Redbird. The aspiring artist was sharing the bill and they hit it off after reflecting on their similar pasts.

“We both experienced the good, the bad and the ugly of the dominant culture,” Redbird said.

“We’d both been adopted as children. We’d both grown up in foster homes.”

Their instant connection proved lasting, and for decades they were inseparable friends, sharing a goal of establishing themselves as mainstream Indigenous artists.

Often, they also shared the experience of record executives shooting down their dreams, unconvinced that an Indigenous artist could sell records.

“It was always: ‘Well, you don't have an audience,'” Redbird said.

“We agreed with them. There was no market because we would’ve had to create a market.”

And so, after many cold shoulders, the pair took matters into their own hands, forming their own record label called Native Country.

“As ridiculous as that sounds, we went for it,” Redbird said, “It just showed that it was possible.”

The Native Country label was short-lived, with only Shingoose’s 1975 EP released on it, but as far as they were concerned, the symbolism was powerful.

The album included “Silver River,” a track of Redbird’s poetry sung by Shingoose, with a young Bruce Cockburn on acoustic guitar.

Cockburn also produced the album, and he said working alongside an Indigenous musician left a lasting impression on him during an era when the cultures hardly ever crossed.

“He really was the first Aboriginal person that I got to know fairly well,” Cockburn said.

“My understanding of (their) experience in Canada really started with Shingoose and (actor and singer) Tom Jackson.”

Decades later, Shingoose's “Silver River” would appear on the compilation "Native North America Volume 1," earning a 2016 Grammy Award nomination for best historical album. It lost to Bob Dylan's "Basement Tapes."

The 1970s proved fruitful for Jonnie, who signed a five-year songwriting deal with Glen Campbell, though it eventually fizzled when the American singer shifted his creative directions.

It took another two decades before Jonnie left his most lasting impression on Canada's music scene when he approached the Juno organizers over the lack of representation at their awards show.

Alongside Sainte-Marie and Elaine Bomberry, he campaigned for the Junos to give Indigenous artists their due in their own category, an effort many felt was long overdue.

Their efforts led to the creation of the Best Music of Aboriginal Canada award in 1994. Since then, it's undergone numerous changes to keep up with the times, but at its heart, the goal remains the same: to put a spotlight on Indigenous music.

A statement from Juno organizers recognized Jonnie's impact in creating the honour, now called Indigenous Artist or Group of the Year, and called him “a trailblazer for Indigenous music and activism in Canada.”

Redbird said despite his friend’s stroke nearly a decade ago, he often spoke about returning to the stage for another big show when the pandemic subsided.

While he never got to see those days, Redbird said he's thankful for the memories.

“He has a big moccasins footprint on this world,” he said.

“I'm glad he was here for the time the Creator allowed him to be.”

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Jan. 13, 2021.

David Friend, The Canadian Press