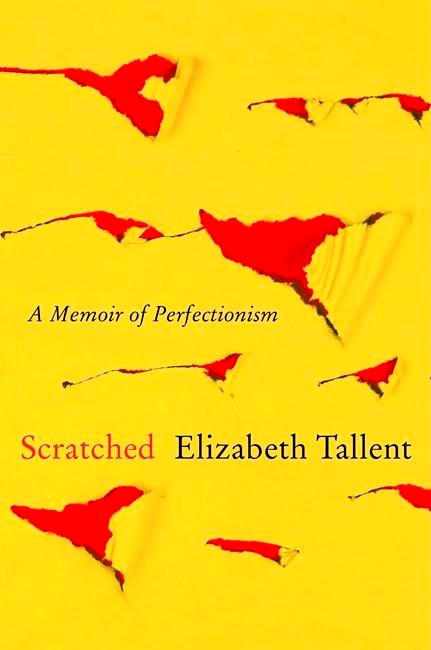

“Scratched: A Memoir of Perfectionism,” Harper, by Elizabeth Tallent

In the 1980s, Elizabeth Tallent was a rising star in the literary world, publishing short stories and books to great acclaim, only to fall silent for the next 22 years. Her memoir, “Scratched,” is her account of why she stopped writing — even as she was teaching creative writing at Stanford — and how she started again.

It’s a harrowing story of overcoming perfectionism, leavened by her dry wit and precise, poetic use of language. Written in a fractured, stream-of-consciousness style that weaves in excerpts from books and articles by psychologists, it begins with her birth in 1954 in a suburban Washington, D.C., hospital.

To the shock and consternation of the nurses, Tallent’s mother refused for several days to hold her daughter, repulsed by the fingernail scratches the infant inflicted on herself in utero. Hence the title “Scratched.” Years later, Tallent’s mother tells her this story with no apologies, justifying her actions by saying she thought newborns came out “perfect (and) smiley,” like those on a Gerber’s baby food label.

And so, from her very first moments of consciousness, Tallent intuits that she is unwanted, imperfect, unloved and unlovable — a fatally flawed, scratched mistake in need of perfecting. Over the course of the book, as she moves back and forth in time, she describes her bourgeois upbringing, relationships with friends and lovers, and intermittent efforts to grapple with her neuroses.

We meet her beloved son Gabriel from a first marriage, with whom she has absolutely no problem bonding; a couple of her gurus and therapists, including a Freudian analyst with whom she has a brief second marriage; and finally, an antiques dealer in Mendocino, California, who becomes her third spouse and wife, and to whom the book is dedicated.

At the beginning Tallent assembles three epigraphs: one from a psychologist known for his research on perfectionism; another from Virginia Woolf, whose modernist sensibility and tortured psyche find echoes in Tallent’s writing; and one from the great Japanese fashion designer Yohji Yamamoto, who expresses a point of view that is the opposite of perfectionism.

He says, “I think perfection is ugly. Somewhere in the things humans make, I want to see the scars, failure, disorder, distortion.” This book is a record of Tallent’s struggle to show her scratches and to believe, as her young son tells her one day after spilling a glass of milk, “Everybody makes mistakes.”

Ann Levin, The Associated Press