WASHINGTON — In moments of crisis, of war and terror, of loss and mourning, American leaders have sought to utter words to match the moment in hope that the power of oratory can bring order to chaos and despair.

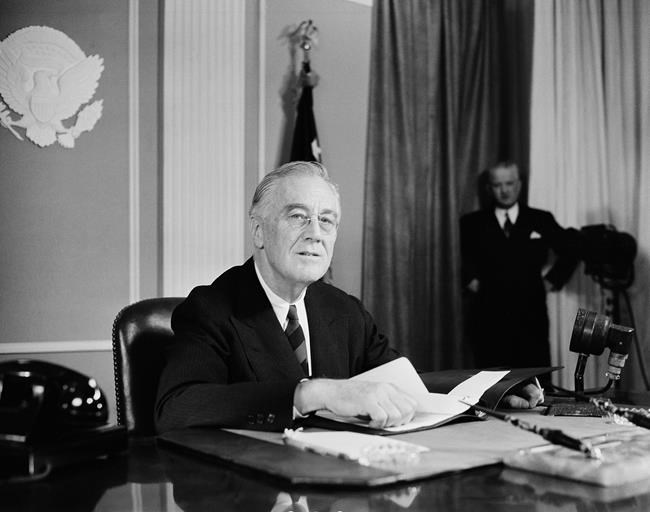

Lincoln at Gettysburg. Franklin Roosevelt during the Depression and World War II. Reagan after the Challenger disaster. Bill Clinton after the Oklahoma City bombing. George W. Bush with a bullhorn at Ground Zero in 2001 and Barack Obama after the slaughter of congregants at a South Carolina church.

Each time, the speakers, Republican and Democrat, extemporaneously or with a script, managed to sound notes that brought at least a temporary sense of national unity and purpose.

“I really think there is something at the very core of our humanity that only words can satisfy,” said Wayne Fields, author of “Union of Words: A History of Presidential Eloquence," and a professor at Washington University in St. Louis. “Almost as much as our need to be touched in the most desperate of circumstances is our need to be spoken to. Public despair in particular has to be literally addressed, I think, if it is to be overcome, must be articulated and then transcended.”

In the aftermath of a violent insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, a cathedral of democracy, President Donald Trump did not meet that prescription. He scaled the walls of false equivalency and descended into the canyons of conspiracy.

He stirred the riotous mob with his “fight like hell” speech before his supporters marched to the Capitol, then delivered a tepid appeal for nonviolence, telling his supporters he loved them. This came well after the man voters chose to succeed him, President-elect Joe Biden, had summoned outrage, empathy and a sense of a path forward.

Trump has never been much for the big speech. Those he has given, like his Oval Office address about the pandemic in March, contained more than one large error. His preferred medium was Twitter, where his 280-characters-at-a-time rhetoric was a study in hortatory rather than oratory. And by Friday, Twitter had shut down his account permanently.

The oratory of crisis typically consists of either a formal statement or an extemporaneous speech. Bush’s initial speech after

Using a bullhorn, Bush responded: “I can hear you! I can hear you! The rest of the world hears you. And the people who knocked these buildings down will hear all of us soon.”

Other presidents have made more direct appeals for healing. Ronald Reagan, poised to deliver a State of the Union address, had to pivot to address the national tragedy of the explosion of the space shuttle Challenger, and the loss of its crew of seven, including the teacher Christa McAuliffe.

“I know it is hard to understand, but sometimes painful things like this happen," Reagan said. "It’s all part of the process of exploration and discovery. It’s all part of taking a chance and expanding man’s horizons. The future doesn’t belong to the fainthearted; it belongs to the brave. The Challenger crew was pulling us into the future, and we’ll continue to follow them.”

Clinton was known for his feel-your-pain persona, on display after the Oklahoma City bombing. “You have lost too much, but you have not lost everything," he said. "And you have certainly not lost America, for we will stand with you for as many tomorrows as it takes.”

After the killing of congregants at Mother Emanuel church in Charleston, South Carolina, Obama sang the hymn “Amazing Grace” and also challenged the nation. “At some point," he said, "we as a country will have to reckon with the fact that this type of mass violence does not happen in other advanced countries. It doesn’t happen in other places with this kind of frequency. And it is in our power to do something about it.”

Unlike Trump, Biden was unsparing in his remarks after the insurrection at the Capitol about where blame lay. “They weren’t protesters," Biden said. “Don’t dare call them protesters. They were a riotous mob, insurrectionists, domestic terrorists. It’s that basic. It’s that simple.”

But Biden also promised a better day ahead, saying that the rioters did not represent the “true America.”

“Oratory in such times, just by being composed at a time when things are falling apart, reassures and opens a door for positive responses and for hope,” Fields said. “Ironically, in being spoken to we can be reassured that we are being heard, that the fears and emotions we have been too distressed to compose, can be articulated, can be expressed.”

Most times, presidents themselves don’t write the words that are most remembered, but their speechwriters know their voice and sentiments. Obama and Clinton heavily edited their speeches; Lincoln wrote many of his own. The most memorable words from Trump's inaugural address were about the need to end an “American carnage” that existed mostly in his own mind.

Soon, Biden’s words will be the ones the nation examines. He has a mixed history with oratory. His first presidential campaign ended largely because he appropriated language from a British politician, Neil Kinnock, a literary theft that today seems almost benign. But Biden even then, in 1987, was also known for his ability to use words, albeit sometimes too many of them.

The president-elect is fond of both lofty rhetoric spoken with an eye to history and the common language of the union hall. He will need to summon both in the days ahead, navigating the fractious end to the Trump presidency and imploring the nation to turn the page.

The word crisis has its origins in the Greek language. Loosely translated, it means the stage of a disease where one lives or dies. It can be overused in the modern context, but few would argue the American democracy is not facing one. The challenge for crisis oratory is to not underplay the severity of the problem or foster a new sense of panic.

The most effective oratory has, at its core, a sense of authenticity, which plays to Biden’s strength.

“Words matter. Words can explain, inspire, console, and heal. In the past, presidents have tried to do these things, with various degrees of success,” said John J. Pitney, a professor of politics at Claremont McKenna College, adding: “Trump is unique in that he has made things much worse.”

___

Michael Tackett, deputy Washington bureau chief for The Associated Press, has been covering politics and government since 1986. Follow him on Twitter at http://twitter.com/tackettDC

Michael Tackett, The Associated Press