WINNIPEG — A judge is expected to decide this week whether a man who admitted to killing four Indigenous women in Winnipeg did so because he was in the throes of a psychotic episode or was driven by a rare form of perverse sexual interest.

The tragic case dating back to 2022 renewed calls for governments and organizations to address the ongoing issue of missing and murdered Indigenous women.

Countrywide protests were also held demanding a search of a landfill for the remains of two of the victims. The search is set to start in the fall.

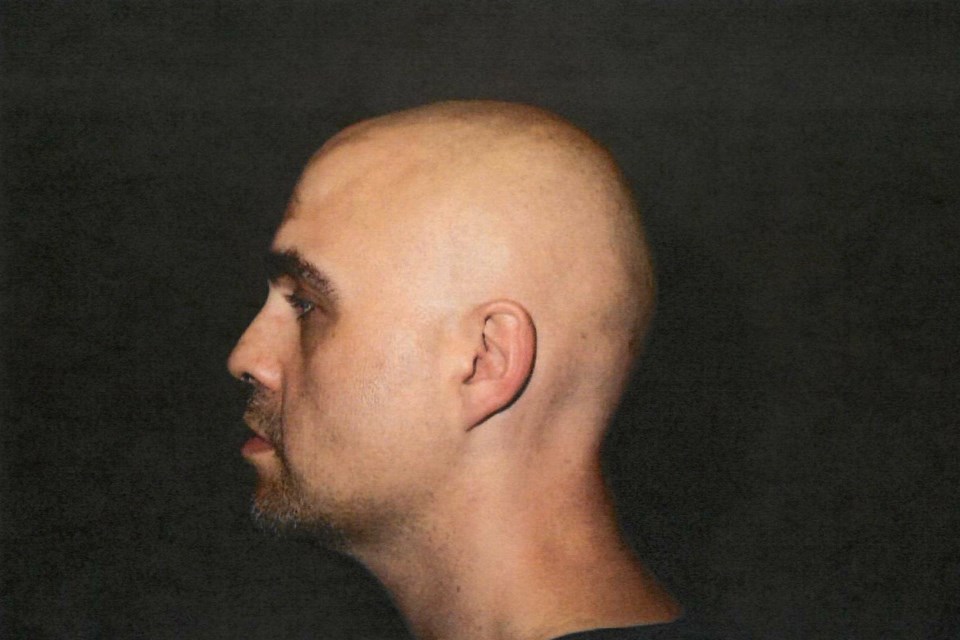

The judge is scheduled to give his verdict Thursday in the first-degree murder trial of Jeremy Skibicki.

Skibicki has admitted to killing Morgan Harris, 39; Marcedes Myran, 26; Rebecca Contois, 24; and an unidentified woman an Indigenous grassroots community has named Mashkode Bizhiki'ikwe, or Buffalo Woman.

Defence lawyers have argued the 37-year-old Skibicki should be found not criminally responsible due to mental illness. A forensic psychiatrist for the defence testified Skibicki was suffering from schizophrenia at the time of the killings.

But the Crown contends Skibicki killed the women because he is a homicidal necrophiliac and that he knew what he was doing was wrong.

Homicidal necrophilia isn't well understood or documented, say some criminologists. It's an uncommon paraphilia where individuals are aroused by having sex with someone they've killed.

Eric Beauregard, a professor of criminology at Simon Fraser University, said there are a few studies on homicidal necrophilia, but it's not well researched.

"We're talking about something very severe and also very rare," he said.

One of the most well-known cases is American serial killer and sex offender Jeffrey Dahmer. Some of his murders involved necrophilia.

Cases of these nature in Canada can be counted on two hands, said Michael Arntfield, a criminologist and professor at Western University.

Beauregard has studied patterns of necrophilic behaviour in sexual homicides. It's often associated with serial offenders.

"It has to be recurrent and intense. It's not something somebody would have experienced once and then you get the diagnosis," said Beauregard.

The causes are unclear.

“That’s the million-dollar question criminal profilers, criminal psychologists, psychiatrists and police investigators have been trying to get to the bottom of," said Arntfield.

Research suggests offenders experienced a traumatic event during their childhood.

Skibicki's trial heard he has a history of mental illness, including depression, borderline personality disorder and thoughts of suicide. But there was no diagnosis of schizophrenia from a psychiatrist throughout his years of treatment.

Dr. Sohom Das, a forensic psychiatrist from the United Kingdom, assessed Skibicki after the killings and testified for the defence. He said he believes delusions and the psychotic symptoms caused by schizophrenia directly motivated the slayings.

Das said Skibicki told him that he felt compelled to kill the women because he was on a mission from God and heard hallucinations coaxing him to kill.

Prosecutors have argued the opposite, presenting DNA, video surveillance and witness evidence to show Skibicki had the mental capacity and awareness to commit and cover up the killings.

They also argue Skibicki targeted the women because they were Indigenous.

In an unprompted confession to police, Skibicki told police the killings were racially motivated and cited white supremacist beliefs.

Prosecutors said Skibicki preyed on the victims at homeless shelters. He then assaulted them, strangled or drowned them, before committing "vile, sexual acts" on their bodies.

The trial heard he disposed of the bodies in garbage bins in his neighbourhood. Myran and Contois were dismembered.

Dr. Gary Chaimowitz, a Crown-appointed forensic psychiatrist, testified Skibicki is likely a homicidal necrophiliac and was driven to kill the women because of his sexual interest in the dead.

Chaimowitz told court that Skibicki has a record of necrophilia interests dating back to his early teens. Chaimowitz said Skibicki told him he had been aroused by people playing dead or who were dead.

The trial also heard Skibicki sexually assaulted his former wife while she was sleeping. The ex-wife testified Skibicki had a fetish for her being lifeless, and he showed her violent pornography and suggested they re-enact it.

Research suggests there are nine types of necrophilia. The first involves an element of role-playing that escalates.

"People become increasingly exploratory and risk-taking," said Arntfield.

"Once you're to that level of depravity, it's very difficult to control. There's no sort of anodyne substitute for what you're doing in order to keep you fulfilled."

However, paraphilias by themselves do not require psychiatric treatment, said Arntfield.

"Necrophilia in itself doesn't make you criminally insane, for lack of a better word ... those people are perfectly able to function."

Beauregard said the true prevalence of necrophilia is unknown, given that investigators aren't always familiar with the behaviour.

"Sometimes it is very easy to miss the sexual dynamic that went on in the homicide. This is why a lot of these cases are not flagged as sexual, when in fact they are," said Beauregard.

Arntfield said police should undergo more training to allow them to recognize and classify behaviours associated with the paraphilia.

The federal government has a support line for those affected by the issue of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls: 1-844-413-6649. The Hope for Wellness Helpline, with support in Cree, Ojibway and Inuktitut, is also available to all Indigenous people in Canada: 1-855-242-3310.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published July 9, 2024.

Brittany Hobson, The Canadian Press