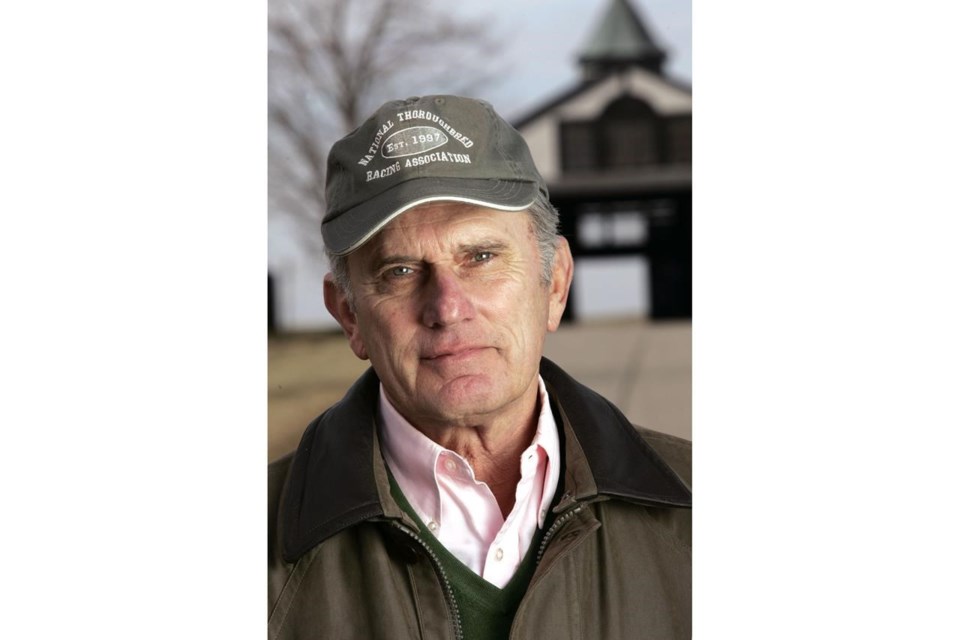

FRANKFORT, Ky. (AP) — Former Kentucky Gov. Brereton C. Jones, a Republican turned Democrat who led efforts to improve health care and strengthen ethics laws during his one term three decades ago, has died, Gov. Andy Beshear said Monday.

Jones was a prominent horse breeder whose political career began in his native West Virginia, where he was elected to the House of Delegates as a Republican. He moved to Kentucky and switched parties, first winning election as lieutenant governor before running for and winning the state's highest elected office.

He also survived two serious accidents while in office from 1991 to 1995 — a helicopter crash and a fall from a horse. Both accidents left him with a severely injured back.

“Gov. Jones was a dedicated leader and a distinguished thoroughbred owner who worked to strengthen Kentucky for our families,” Beshear said in a social media post Monday.

He said the family has asked for privacy but more details would be shared at a later date.

Jones' administration was memorable for a well-intentioned yet ultimately unsuccessful attempt at universal health insurance.

He envisioned a system in which coverage would be accessible and affordable for everyone in the state, regardless of health history. Instead, dozens of insurers bailed out of Kentucky, and costs for individual coverage soared.

During his time as the state's top elected official, Kentucky governors had to step aside after serving one term. Jones pushed to change the state Constitution to allow statewide elected officials to run for reelection for a second term. When the amendment passed, it exempted current officeholders like himself.

Reflecting on his term shortly before leaving office in 1995, Jones said he warmed to the job.

“I hated the first year,” he told an interviewer. “The second year, I tolerated it. I liked the third year, and the fourth year, well, I’ve loved it. It all passes so quickly.”

After leaving the governorship, Jones returned to private life at Airdrie Stud, a horse farm in central Kentucky.

Jones jumped into Kentucky politics by winning the 1987 race for lieutenant governor. His campaign was largely self-funded from his personal wealth. He worked through his term as lieutenant governor and into his term as governor to recoup the money.

In his run for governor in 1991, Jones promised to set a new ethical standard for the office. He also held himself out as someone above partisan politics. “I’m not a politician,” he was fond of saying, though he had been elected to office in two states, two parties and two branches of government.

Jones went on to win in a rout against Republican Larry Hopkins.

Once in office, Jones got the legislature to create an ethics commission for executive branch officials and employees. But despite his frequent speeches about ethics, Jones seemed to many to have a blind spot when it came to his own finances and business dealings.

Also under Jones, the legislature enacted its own ethics law, with its own ethics commission, following an FBI investigation of a legislative bribery and influence-peddling scandal.

The major initiative of Jones’ administration was access to health care and controlling the cost of health coverage. But the heart of the initiative was an ultimately ill-fated experiment in universal health care coverage.

Insurers were forbidden to consider a person’s health when setting rates. No one could be denied coverage as long as they paid the premiums. Insurance policies were expected to be standardized — thus theoretically easier for consumers to compare — and a state board was created to regulate them.

Insurance companies refused to accede. A number of companies pulled out of Kentucky. Premiums shot upward as competition nearly disappeared. The initiative later was gutted or repealed by lawmakers.

Bruce Schreiner And Dylan Lovan, The Associated Press