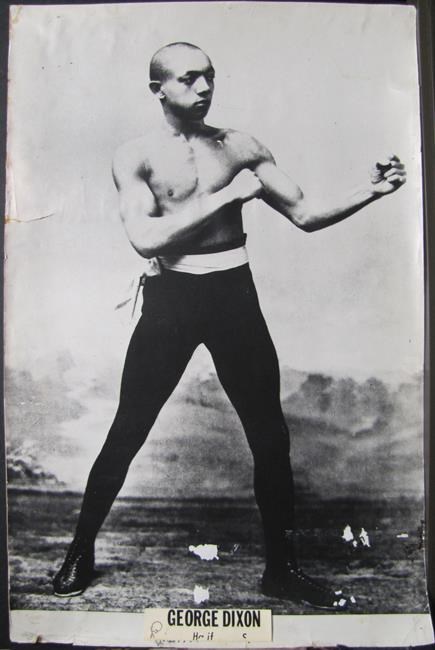

HALIFAX — George Dixon stood five-foot-four and at most weighed 115 pounds during his career, but he was a giant in the boxing ring.

In the late 1800s, the lightning-fast Nova Scotian became the first Black boxer and first Canadian to win a world title, a remarkable feat for a man whose life and career were marked by racial prejudice and discrimination.

At a ceremony Monday on the Halifax waterfront, about 50 people gathered to pay tribute to Dixon at the Africville Museum in the city's north end, the site of the once-thriving African Nova Scotian neighbourhood where the boxer grew up.

Andy Fillmore, the MP for Halifax, told the audience that Dixon had been selected as a person of national historic significance because his impact on history continues to inspire others to this day.

"Before there was Joe Louis and Muhammad Ali, there was George Dixon," Fillmore said before he helped unveil a Parks Canada historic plaque. "Dixon not only shattered racial barriers but also proved to the world that talent and determination know no bounds."

Even though Dixon faced segregation and adversity throughout his life, "he never let those obstacles define him or limit his potential," Fillmore said. "Dixon's athletic triumph was not just a personal victory, but a win for equality and social justice."

Born in 1870 in Africville, Dixon was renowned for his stamina, speed and innovative training methods.

His first official fight was in Halifax in 1886, when he knocked out Young Johnson. For the next four years, he fought in Boston. And in 1890, he travelled to England, where he knocked out Edwin "Nunc" Wallace in the 18th round to win the world bantamweight title.

Dixon then moved up a weight class to win the featherweight world title in 1891 — the second honour marking another first for professional boxing.

Known for his quick hands and fast footwork, Dixon is credited with inventing shadow boxing, a training technique still in use. He is also known for using his fame as a platform to promote Black boxers. His 1893 book, "A Lesson on Boxing," described his winning strategies and innovative training regimen.

"George Dixon had to work hard at his sport while facing bigotry, Jim Crow discriminatory practices and the overt racism of the day, making his accomplishments all the more astonishing," said Craig Smith, a local historian.

"George Dixon became the most famous Black person in the world in the face of that adversity."

Dixon's last fight was in 1906. He died in New York in 1908 and is buried in Boston's Mount Hope Cemetery.

During the ceremony on Monday, eight people stood up to be recognized when the crowd was asked if anyone was related to Dixon. Terrie Dixon was one of them.

"All of our ancestors are looking down upon us now with great smiles," Dixon, who described herself as a distant relative of the fighter, said in an interview. "We are just so proud and grateful that we are here today to celebrate him."

Aaliyah Arab-Smith, another distant relative, said the plaque unveiling left her feeling inspired.

"Having a plaque is great, but it's also knowing in our hearts that Africville's spirit lives on," said the young track athlete. "Just knowing that someone related to me has done such great things on a global scale … it's truly inspiring."

Settled in the 1840s by formerly enslaved people, Africville would later become a source of shame for the port city. The impoverished community had no running water, no sewers and little access to electricity or police protection. But its residents were proud of their distinct neighbourhood, which brimmed with its own music and culture.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the city expropriated all of the community's properties and razed what it said were "blighted houses and dilapidated structures" in the name of urban renewal. On Jan. 2, 1970, the last resident of Africville, Aaron (Pa) Carvery, moved out. In all, about 400 people were moved to other parts of the city.

In 2010, the then mayor of Halifax, Peter Kelly, apologized for the destruction of Africville and promised $3 million to build a replica church and interpretive centre. The ceremony on Monday was held on a sprawling lawn next to that centre.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published June 12, 2023.

Michael MacDonald, The Canadian Press