Chances are you've seen or heard some sort of promotion about the value of shopping locally — especially with so many of us in gift-buying mode now.

Business improvement areas, chambers of commerce and other organizations tell us when we buy from shops near home, we're voting for our community.

The logic is generally sound but our habits don't change so easily.

My work (and natural inclination) means I spend a lot of time in and around books. I use libraries extensively but I buy books, too. In that case, it's easiest just to order them online. You get exactly what you want delivered right to you.

So imagine you hear about Nassim Nicholas Taleb's newest title Antifragile and you decide you want to read a diplomacy-free account of how most of the world is wrong.

You may stop by a couple of local bookstores to see if they have it. Often, they don't because they couldn't possibly stock all the wildly different titles you might request. You end up ordering the book online — or, if you're really committed, you order it through the store and come back later to get it.

Those extra steps have meant a real decline in local bookstores over the last decade. Most of us skip checking with a local bookstore.

If we really want to make shopping local the norm, the challenge is clear. We need less transaction efficiency thinking and more enjoyment efficiency thinking. The appeal must be to our enjoyment, the pleasure of a different scenario driven by an older cultural liturgy.

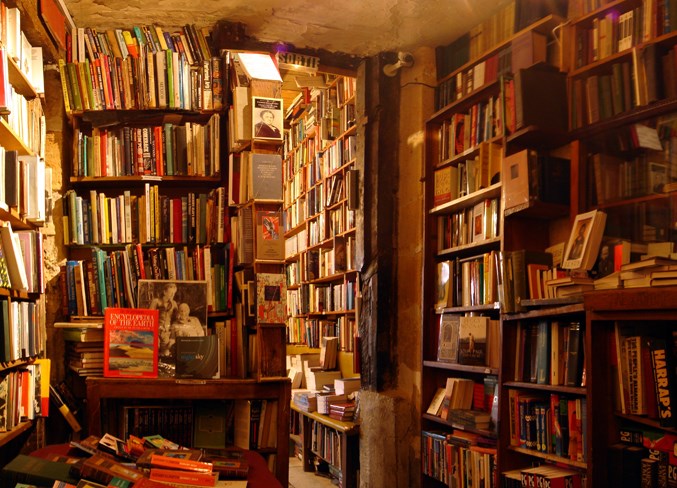

Imagine that you visit your local bookstore, owned and operated by someone who shares your love of books — something you know because you have gone there many times and engaged in a human exchange with the owner, a common practice called a "conversation" (ask someone born before 1990 about it).

You come in asking for the new Taleb. Though the store doesn't have it, the owner knows you well enough to suggest several other in-stock titles along that science and culture line.

Because you've bought many books from the shopkeeper before and trust her sense of things, you sort through the options and end up with Aaron Tucker's novel, Y: Oppenheimer, Horseman of Los Alamos, about J. Robert Oppenheimer's thought life while developing the atomic bomb — no waiting or coming back or ordering.

Of course, you could've just ordered Taleb (or done it on your phone while standing in the store). But instead, a much more enriched human nudge provided a unique option.

This is a different logic, a different cultural liturgy. It's more than a shop local slogan and doesn't appeal to the low motivational power of guilt. Rather than having just what we want when we want it, we accept a limit in exchange for an insight offered through another person.

Buying what a bookstore has, mediated through a knowledgeable bookstore keeper, is like being a locavore — eating what your area provides. You learn to appreciate how you can sustain yourself within a certain range, whether culinary or literary, and realize how much is available nearby.

If we want to see shopping locally take deeper root, we need to accept some limitations as a gift — increasing our enjoyment of life by limiting our choice to what our street, community or neighbourhood provides.

It isn't about policing our neighbours if a courier pulls up and drops off an Amazon parcel. Rather, we can enlarge our pathways to include the pleasure of the shops, the meetings and the passing conversations that exist around us. Many such places have disappeared but you can usually find some form of them around.

Consider this bit of recent good news from the American Booksellers Association: many local bookstores are growing and some are booming. Our appetite for the pleasure of discovering is kicking back in.

For all the local businesses you'll walk (or likely drive) past this Christmas, perhaps you'll consider what it might be like to become a regular in a shop that may yet have the power to surprise and delight.

Milton Friesen directs the Social Cities Program at the think-tank Cardus.

© Troy Media