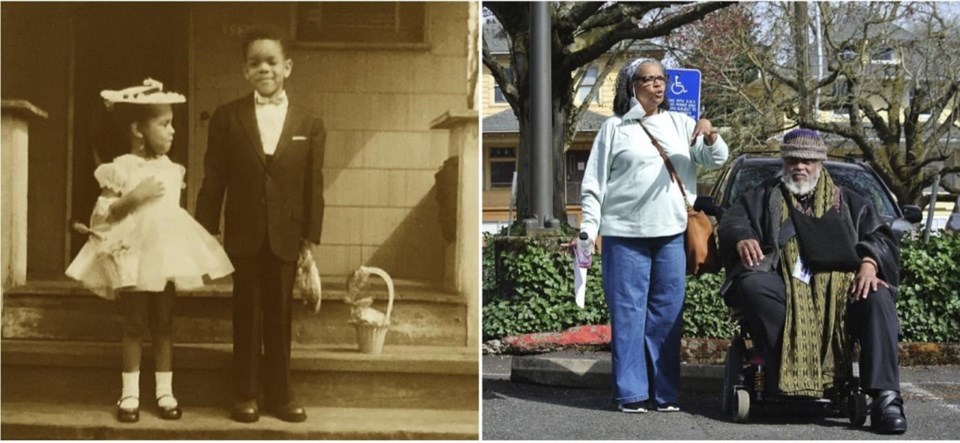

Bobby Fouther's childhood home is now a parking lot, the two-story, shingle-sided house having been demolished in the 1960s along with many other properties in a predominantly Black neighborhood of Portland, Oregon.

“Growing up there was just all about love,” Fouther said.

Fouther and his sister, Elizabeth Fouther-Branch, are now among 26 Black people who either lived in the neighborhood or who are descendants of former residents who are suing Portland, the city's economic and urban development agency and Legacy Emanuel Hospital, accusing them of the “racist” destruction of the homes and forced displacement.

The lawsuit, filed Thursday in federal court in Portland, shines a light on how urban improvement projects and construction of the nation's highways often came at the cost of neighborhoods that aren't predominantly white.

“In many cases, city and state planners purposely built through Black neighborhoods to clear so-called slums and blighted areas,” according to a 2020 report by Pew Charitable Trusts, a Pennsylvania-based nonprofit public policy group.

People who were part of racial minorities were often obligated to live in those neighborhoods because of “redlining” — banks discriminating against home loan applicants based on race — and even due to laws that maintained all-white neighborhoods.

That was the case for Fouther's family, who couldn't get loans elsewhere, Fouther said.

“Because we had that community relationship, we were able to purchase that house," he said in a video statement provided to news outlets.

But even after buying homes and building lives in the Albina neighborhood of Portland, residents were forced to move by so-called urban renewal and highway building.

Albina had already been partially destroyed and carved up in the 1950s and ’60s by the building of Interstate 5 and Veterans Memorial Coliseum, the original home of the NBA's Portland Trail Blazers. But then a hospital expansion was announced.

Between 1971 and 1973, the Portland Development Commission demolished an estimated 188 properties, 158 of which were residential and inhabited by 88 families and 83 individuals. A total of 32 business and four church or community organizations were also destroyed, according to the lawsuit. Of the forcibly displaced households, 74% were Black.

A first phase, in the 1950s and '60s, involved city officials secretly agreeing to compensate the hospital for the full cost of the purchases and demolitions, the lawsuit said. The homeowners were intimidated by hospital representatives and told that if they didn’t leave, the city would take their homes. They were not fairly compensated and in some cases not compensated at all, according to the lawsuit.

“This case is about the intentional destruction of a thriving Black neighborhood in Central Albina under the pretense of facilitating a hospital expansion that never happened,” the lawsuit says, adding that the loss of homes "has meant the deprivation of inheritance, intergenerational wealth, community, and opportunity.”

Much of the land that used to be a thriving neighborhood, where Black families felt safe and had social and spiritual connections, became parking lots or stood vacant.

“I was taken out of my safe and loving community. I was moved into a neighborhood that saw me as a nuisance and to a school where I was one of three Black children,” said Connie Mack, one of the plaintiffs.

The lawsuit said the defendants are benefiting from "unjust enrichment" from “this horribly racist chapter from Portland’s past.”

Legacy Health, which owns Legacy Emanuel Medical Center, declined to comment on the lawsuit, saying it is evaluating it. Prosper Portland, formerly the Portland Development Commission, also said it is evaluating the complaint and had no additional comment. City officials didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Albina is now called the Eliot neighborhood, which boasts trendy shops, cafes and eateries.

“Our neighborhood, in the heart of the former city of Albina, is a great place to live, work and play,” the Eliot Neighborhood Association proclaims on its website.

Many of the plaintiffs' homes, if they had not been destroyed, would have been worth more than $500,000 today, the lawsuit says.

The plaintiffs are seeking compensatory damages from defendants in amounts to be determined at trial.

Andrew Selsky, The Associated Press