SUNDRE – A society that depends on a finite resource cannot indefinitely continue to grow without facing serious consequences, and future sustainability must factor in ecological limits and thresholds.

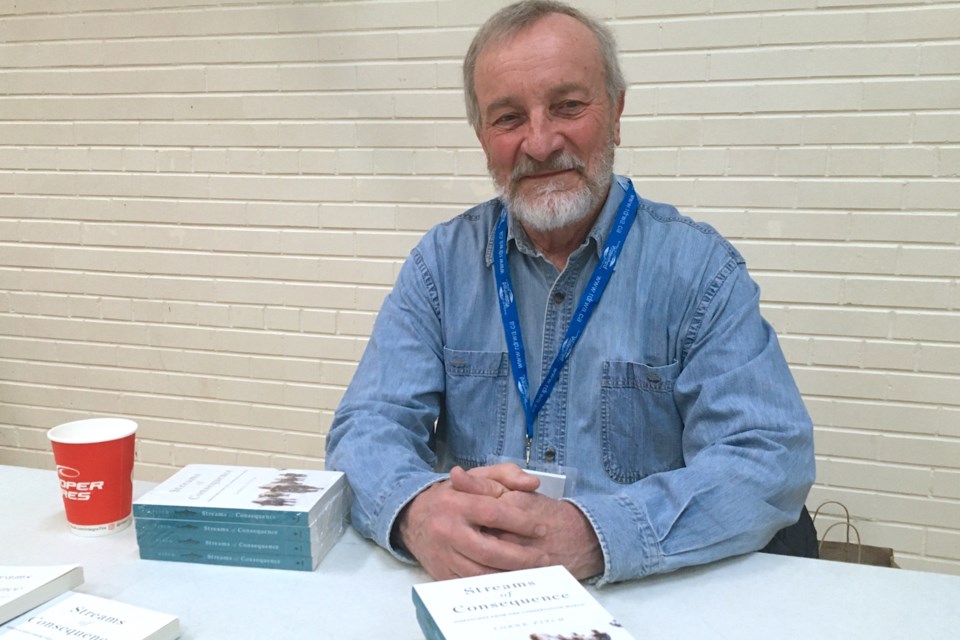

This was among the key messages presented by a former Fish and Wildlife biologist with more than 40 years of experience who spoke to a crowd of about 60 on Friday, May 3 at the Sundre Community Centre during an expo organized by the Red Deer River Watershed Alliance.

The two-day event started on May 2 with hundreds of students from kindergarten to Grade 10 attending. More than 10 groups including the Legacy Land Trust Society and the Native Trout Exhibit also participated.

“The real measure of wealth, is water,” said Lorne Fitch to a crowd of several dozen people.

“Very soon, maybe in the throes of the next drought, we will understand water is the most expensive natural resource for our survival,” said Fitch.

Far from inexhaustible supply

That’s a reality that communities in southern Alberta such as the MD of Pincher Creek understand quite clearly, especially since the level of the Oldman reservoir dropped below their water intake, he said.

“They have been hauling water since last year to several communities at the cost of $8,000 per day. They know the value of water. Also its cost” and by extension limits and thresholds that have already been exceeded in some reaches of rivers and streams in southern Alberta, he said.

“Some parts of the year, the reaches of many of those rivers no longer function as biological entities with a full spectrum of ecological processes, functions and benefits,” he said.

“Rather, they are degraded systems without enough flow; those phenomena should be a warning and not a target for other watersheds to aspire to – nudge nudge, wink wink,” he said in a not-so-subtle message to the crowd.

Whether agricultural, municipal, industrial, commercial or resource extraction, all sectors of the economy “must accept and work carefully within the limits of the water cycle, it being far from an inexhaustible supply,” he said.

In Alberta, portions of the province were made blue through irrigation, while at the same time turning other parts dry through drainage, mining and timber harvest, he said.

“Some water we pour down holes we drilled in the ground,” he said.

“It’s an irony given that all recent space travel and exploration to other planets have been a search for water. As Calvin and Hobbes say, ‘Sometimes I think the surest sign that intelligent life exists elsewhere in the universe, is that none of it has tried to contact us,’” he said.

This “profilgate cavalier attitude to water” has to change, he said.

“As a function of history, the decisions about water management over the last 100 years have provided substantial economic benefits, created ecological consequences, and foreclosed on other opportunities for other choices given the challenges of an uncertain future,” he said.

“We find ourselves at a pivotal point that requires us to reflect about the past, understanding our present circumstances, and weigh the trends and trajectories to plan a future that maintains a mix and balance of economic opportunity, environmental protection and social needs for the residents of the watershed.”

Native fish populations key metric

It’s important to understand that a watershed requires a certain amount of water in order to service its own needs before sustainably satisfying our own, he said, adding there is also a key metric thousands of years in the making that can help us gauge a watershed’s health.

“The metric is fish,” he said, whether they be native trout varieties in headwaters or species such as walleye and pike in the Prairie systems.

“If you consider their 12,000-plus years of experience at coping and evolving in Alberta’s watersheds, fish are the gold seal of water quality and of watershed integrity,” he said.

“How well we have managed the watersheds is embodied in the diversity and population response of those fish. It’s applying a fish ruler to see how our management measures up,” he said.

“I wish I could say we’re managing well using native fish as a metric. But we’re not,” he said.

“Most of the native fish in the headwaters are species at risk; either threatened or in danger. That should be a signal.”

Throughout the millennia, fish have endured and evolved through storms, floods, droughts, changes in water temperatures, and along the way adapted the natural variability of their world into their genetic material as a survival mechanism, he said.

“What they have not adapted to – cannot adapt to – is the speed and magnitude of the changes we have brought to their world in a period of time as short as one human lifespan,” he said.

While existing infrastructure might offer some options and a level of flexibility to deal with some future concerns, future water management efforts may well need to be better attuned to the needs of the watershed, he said.

Confronting the myth of water abundance

Improving water management plans amid an increasing population and growing developments placing greater and greater pressure on a shrinking resource will first require confronting a common misconception.

“We might begin – we must begin – by thinking and dealing more critically, forcefully and proactively with the perception, or myth, of abundant amounts of water in Alberta,” he said.

Citing 18th century philosopher Edmund Burke, Fitch said, “The great error of our nature is not to know where to stop, not to be satisfied with any reasonable acquirement, not to compound with our condition; but to lose all we have gained by an insatiable pursuit after more.”

“There is no magic available to make more water,” he said, adding, “It will always be a limiting factor.”

Water can of course be pumped uphill; provided there’s enough energy and money to do so, he said.

“But that has undesirable side effects and represents a failure to confront and heed ecological limits,” he said, adding such an approach also runs the risk of creating winners and losers in the race for water.

“There is magic in cleaning the quantity we have polluted,” he said. “But that magic is expensive. And the cost of clean up often comes out of the pocket of downstream users, not the entity that originally changed the quality of it.”

Ecology should guide policy making

Environmental thresholds should guide the hands of policy makers. What he called noble efforts to protect watersheds in the past have seemingly deteriorated “into a contest of dividing up flow and putting in place an economic development plan with a dubious lifespan” that “becomes based on ideology and technology rather than ecological thinking.”

Planners, technocrats, bureaucrats, policy analysts are generally more preoccupied with making arrangements that are more profitable, he said.

“A more reasonable strategy often promoted by community watershed groups, is to focus on community needs and how those can be met with the least interference with the overarching water cycle,” he said.

While the responsibility of protecting the provincial water supply ultimately falls on the shoulders of governments, academics, and business communities, everyone needs a nudge, he said.

“Governments react to public pressure. Scientists can tell us what is happening, but can’t make us do anything about it. Business won’t move until legislation or the marketplace dictate the change,” he said.

“And communities and individuals need an honest broker for information, plus support and motivation to make – and keep making – changes.”

It’s not that there are no visions for watersheds, but rather more likely there are too many small visions instead of a larger, all-encompassing one, he said, adding we all tend to see the world through the lens of our own individual ideals.

“When will we care for water better? The answer is: when enough people speak out. In all things, a new attitude is the only lasting solution,” he said.

“We need to create a collective vision through awareness, research and advocacy,” he said. “I’m pleased that at least the number of people in this room indicate that that might be a path forward.”

Staying within limits

Speaking with the Albertan following his presentation, Fitch said when asked what he hoped people who attended his presentation took away from it was – first of all – limits and thresholds.

“We can’t continue to mine the Eastern Slopes. We can’t continue to divert flow from the river. We can’t continue to change the landscape and not expect some negative consequences,” he said.

“Sooner than later, we have to recognize that we weren’t given the landscape of this watershed in the sense that we can continue to develop it infinitum into the future,” he said.

“We can’t do everything, everywhere, all the time, any time and expect that the landscape will support that,” he said.

He also hopes people took away a better understanding of how cumulative effects can impact watersheds.

“We think, ‘Well, we can do one more thing – we can do one more clearcut, one more well site,’” he said.

But such a mentality is nothing more than shortsighted hubris, he said.

“We need good watershed planning; that’s the third pillar of this,” he said, adding that planning needs to be done not only by people who live on a watershed but all Albertans.

“Just because I live in the Oldman Watershed, doesn’t mean that I’m not concerned about the Red Deer River Watershed,” he said.

A call for collective action

As an Albertan, Fitch understands all too well the kinds of responses words such as “collectivism” tend to automatically elicit in the minds of many.

“I appreciate that Albertans like to extoll the fact that we are strong and free and independent,” he said. “But we are not independent from the landscape, and we are not immune from the laws of ecology.”

That means accepting the fact we must be ready to face the consequences of our collective actions; or perhaps inactions.

“My wife and I joke – somewhat facetiously – that because of the ensuing drought, we should keep our bathtub filled with water,” he said. “It’s a big concern.”

Throughout the years he and his wife have called Lethbridge home, Fitch said there had been three instances when there was no water flowing from the tap as a result of water main problems. The drought situation could amplify such problems.

“That is a wake up call about how dire the situation may be,” he said.

Looking back over the past 900 years of the paleoclimate’s trends, the historic drought of the 1930s that by our standards was considered serious, might otherwise have by comparison been deemed a minor wet spell, he said.

“We’ve had much longer droughts, and yet we only have the capacity with our reservoirs for about a two-year, back-to-back drought,” he said.

Further compounding matters is a much larger population than last century coupled with the fact modern Albertans consume vastly greater volumes of water today than did their predecessors.

Government lacks strategy

“What I see with their drought planning is a series of tactics; there’s no strategy,” he said when asked for his thoughts on the provincial government’s response.

Plans to make plans are tantamount to kicking the proverbial bucket along to the next generations, and the government is treating the situation as “a one-off,” he said.

“I think what we need to be doing is using this opportunity to think about how we prepare ourselves for long droughts; how we get ready for the serious implications of a drought that the paleoclimate tells us will happen,” he said, adding climate change is further accelerating and exacerbating the process.

“And of course it’s not just drought; it’s flood as well. It’s the extremes,” he said, adding a one-off deluge may not suffice to replenish thirsty watersheds.

A common refrain Fitch hears making the rounds is the uninspired idea to simply build more reservoirs.

“My stock response is: doesn’t matter how big the gas tank is if there’s no gas to put in it,” he said.

During his time as a Fish and Wildlife biologist, Fitch said he had the opportunity to work on six reservoir projects in southern Alberta.

“At the beginning of every one, was this fervent hope that this was going to solve all of the problems. And as soon as one was built, there was a recognition it didn’t work and we had to build another one,” he said.

“When do you finally acknowledge that you can’t build yourself out of these things; you’ve got to start thinking about ecological limits,” he said.

Raising awareness leads to action

Instead of looking to past methods and practices, policy makers should be looking wisely toward the future, he said.

Fitch fully agreed with the Indigenous proverb that a people do not so much inherit the planet from their ancestors, but rather borrow it from future generations.

“We’re using up the reservations for lunch for our children,” he said.

But forums such as the expo hosted by the Red Deer River Watershed Alliance are an important first step toward raising awareness, which is key to spurring action, he said.

“And stewardship, which is what we need to be extolling in everyone, is an amalgam of three fundamental but indivisible things: awareness is number one, ethics is number two, and then taking action is number three.”