There was nothing humorous about a serious extracurricular research project a dozen Sundre High School students recently embarked on in Saskatoon, but the experience provided a unique hands-on opportunity to practise real-life science.

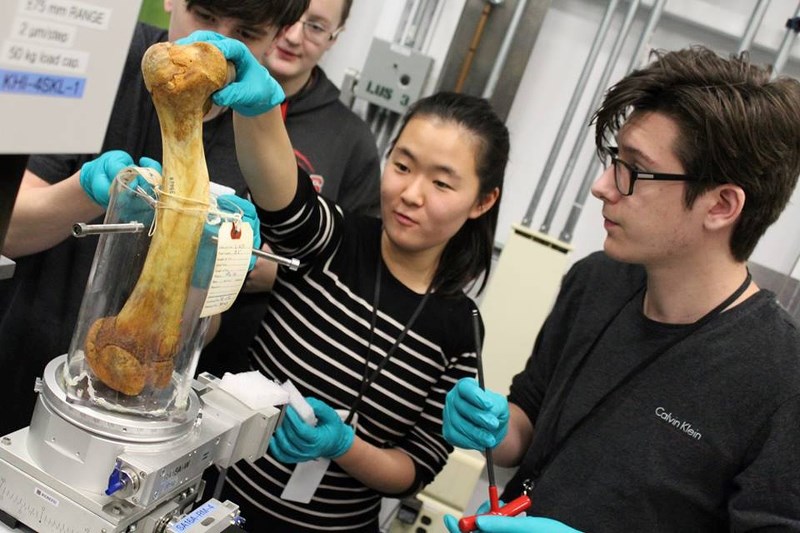

The group of young science enthusiasts in grades 10-12 investigated the effects of PCBs on the bone density of polar bears by analyzing several samples of the animals' humerus ó or forelimb ó bones, which were made available courtesy of the Assiniboine Zoo in Manitoba and from the Canadian Museum of Nature, said Ryan Beck, chemistry teacher.

"They did real scientific research and have been working with top researchers from around the world to help them design their project," Beck told the Round Up.

"We have been working on this since September of last year."

With guidance from scientists, the students used high intensity X-rays produced by the Synchrotron at the Canadian Light Source (CLS), which is located on the grounds of the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon, to see extremely detailed images inside polar bear humerus bones, he said.

They then compared the images from bones dating back to the early 1960s, when there was almost no PCB contamination in the North, to the late 1960s, when the man-made chemical's contamination was at its highest, all the way up to 2016, when PCB levels were stable and low, he said.

PCBs ó or polychlorinated biphenyls ó are a manmade chemical once used in manufacturing that was banned decades ago because of the negative impact on the environment and by extension, human health.

"Normally, polar bears do not get osteoporosis at all. But they do get osteoporosis in the skull and penis bone if exposed to PCBs. Those bones are both cortical bones, which are very dense," said Beck.

"It is not known if they get osteoporosis due to PCB exposure in their spongy bones like the humerus bone. These students will be the first people in the world to study this," he said before the trip.

The initial analysis from their research on Dec. 9 seems to support the idea that the chemical does indeed negatively impacts the animals' bone density, he said last week.

"We did see that our data was consistent with our hypothesis."

The trip was made possible in part courtesy of a $9,500 research grant from BP Canada, and although the group is back in Sundre, their study is far from over.

"There's still a couple of months of work to do yet," said Beck.

"We're going to do some more analysis of the data. We only had a few hours of time to spend analyzing the data (in Saskatoon), and we have about 130 gigabytes of dataÖthere is the possibility of perhaps being able to draw additional conclusions when we spend more time with the data."

The experience also provided the teacher with a unique chance to practise new science.

"It was very fulfilling to have that opportunity," he said.

"Overall, as a science teacher, I probably have an opportunity to make, indirectly, a large contribution to science by getting lots of students more interested in it," he said, adding his chosen path meant forgoing the possibility of contributing directly to a scientific field.

But that was a sacrifice Beck was willing to make for the sake of helping to inspire the next generations of researchers and scientists, he said.

Students such as Danny Kamaleddine, who was among a few other classmates to initially spearhead this extracurricular research last year outside of the school's regular science program.

"We were looking for ideas to do for a big science experiment," he said, adding a few lunchtime group brainstorming sessions eventually led to the idea to study the effects of PCBs on the density of polar bear bones.

Transitioning from learning science theory in the classroom to practising real-life research at a national, state-of-the-art facility was an exhilarating ó albeit initially overwhelming ó experience, he told the Round Up.

"It's a massive building," he said about the Canadian Light Source.

"There was just wires everywhere. But then, realizing exactly what's going on and how it applies to what we're doing, it was just amazing. It all clicked in at once."

Kamaleddine said he was relieved and encouraged to discover the past year's worth of work was substantiated by the data collected throughout the experiments.

"I definitely learned a lot about how to test a hypothesis" as well as applying the scientific method in the real world, he said.

The Grade 12 student, who is also involved in leadership activities and has previously attended Global Vision events, said his goal is to make available for his future as many options as possible.

So whether he pursues a path in leadership and politics or perhaps science and research for now remains to be determined. But Kamaleddine seems committed to considering all potential avenues that he is passionate about.

"All of these (endeavours) open more doors for me."