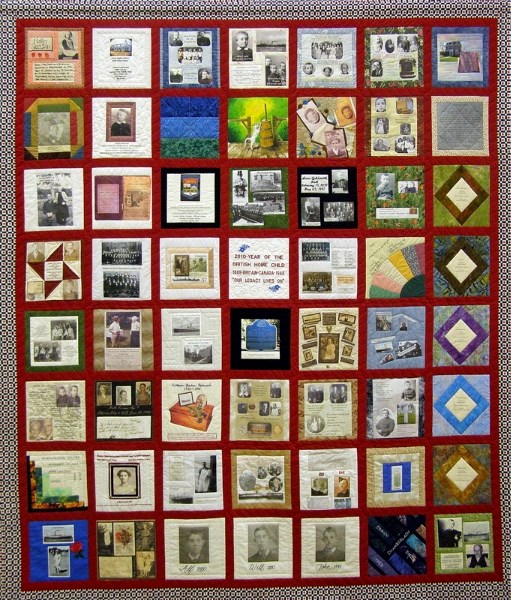

John Vallance's most sacred possession is a battered old brown trunk.It was given to him in 1939. The trunk was for his clothes, a Bible and a little household kit containing a spool of thread, needles and buttons.Vallance is 87 years old today. He had a successful military career for more than 30 years, serving Canada during the Second World War and the Korean War as an army airborne, drill and small arms instructor.Vallance went on to have a successful bartending service in Calgary for 18 years before retiring.But still the old trunk is his most valued possession, a reminder of days when hope for stability was far from certain.“All the boys and girls were given one,” says Vallance. “It was the only thing I had. I kept it all the way through my life.“When I came to Canada I had nothing. I kept it,” says Vallance, who arrived in Wolfe's Cove, Quebec from Portsmouth, England 73 years ago.Most importantly for Vallance, the trunk is a powerful symbol of how he dealt with life after his father agreed to let him go to Canada under a program that saw 100,000 English children endure the same fate.They were the British Home Children (BHC), and John Vallance was one of them.“I am a survivor,” he declares.Their story will be told Sept. 15 and 16 at the Mountain View Arts Festival in Didsbury through Vallance and the celebrated BHC Memory Quilt (AB) that was created by Claresholm's Hazel Perrier, whose grandparents were also sent to Canada under the program.“Bringing this exhibit to Didsbury is part of the society's mandate, to celebrate our culture and all artistic mediums, quilting being one of them,” says Kathleen Windsor, chair of the festival. “In this case, there's more to the art than just the craftsmanship, there's also the stories behind the exhibit.“This is part of our Canadian history,” adds Windsor. “While the exhibit itself is ‘a quilt', the motivation leading to its creation has political, cultural, and social implications.”Beginning in 1869, tens of thousands of orphaned, abandoned and pauper children from England were sent to Canada by British churches and philanthropic organizations with an expectation they would have a better life.Many Canadian families welcomed them as a source of farm labour and domestic help. In some cases they became beloved children for the families but countless others were abused, neglected and overworked.Canada was not the only country to accept BHC. Tens of thousands of others were dispatched to Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. In 2009, the Government of Australia formally apologized for past abuses against BHC. Canada officially proclaimed 2010 as the Year of the British Home Child but it would not issue a formal apology.“There's no need for Canada to apologize for abuse and exploitation suffered by thousands of poor children shipped here from Britain starting in the nineteenth century ... the issue has not been on the radar screen here, unlike Australia where there's been a long-standing interest,” said Jason Kenney, Canada's immigration minister in 2010. “The reality is that, here in Canada, we are taking measures to recognize that sad period, but there is, I think, limited public interest in official government apologies for everything that's ever been unfortunate or [a] tragic event in our history.”Vallance says he was one of the fortunate BHC who did not suffer abuse. He was given over to one of the “better” Canadian families who farmed in an area just outside of Woodstock, Ont. He worked in the fields, learning how to plough, plant corn and feed animals. Two years later he headed west to Willow Bunch, Sask. where he learned how to use a tractor in the wheat fields.In 1943, Vallance joined the Canadian Pacific Railway as a fireman. The following year he joined the Canadian Army, serving 30 years and retiring as a warrant officer.“I'm thankful I left Britain during the war. I'd probably be long gone by now. In Canada I was out of the main action,” says Vallance.But Vallance never saw his father again after 1939. His mother had died a few years earlier. When he came to Canada he left behind two brothers and two sisters.But 60 years later, shortly after his wife Elizabeth died in 1997, he discovered that one sister, Isa, and a brother, George, were still alive. They connected and agreed to meet for a reunion in the Australian island of Tasmania where George resided.“We made newspaper headlines in Tasmania, ‘Siblings reunited after 60 years',” says Vallance.Today Vallance, the “survivor”, is grateful for the life he has been given. He is looking forward to December when he will turn 88 years old. Vallance is aware of the hardships many BHC faced. His life, although not easy, has been one of meaning. He is always happy to share his story.“The only regret I have is not going back to school again. I only have my Grade 8,” says Vallance. “But I was a warrant officer for nine years. I kept playing soccer. I hardly ever smoked or drank, and I am in good shape. Grateful? Yes, I am.”