MOUNTAIN VIEW COUNTY — The ongoing effort to contain an outbreak of avian influenza is not expected to affect the general public, says the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA).

As of Monday, the agency confirmed the presence of highly pathogenic avian influenza, subtype H5N1, at five locations in Mountain View County (MVC), representing a regional increase of two over the long weekend.

The first three — two in MVC and another in Ponoka County — were identified on April 6. Another was found two days later on April 8 in Kneehill County. The following day, on April 9, an outbreak was discovered in Paintearth County. Three more were identified on April 10, 11 and 12, in Wetaskiwin County, Camrose County, and MVC, respectively. Then, on April 14, three more locations were added to the list — two in MVC and one in Warner County. The latest information available prior to press deadline that was posted on the agency’s website also reported that one more location in Cardston County was identified on April 15.

The animals involved in the locations listed above were from commercial poultry flocks in all but one of the instances in MVC, which was attributed to a small flock.

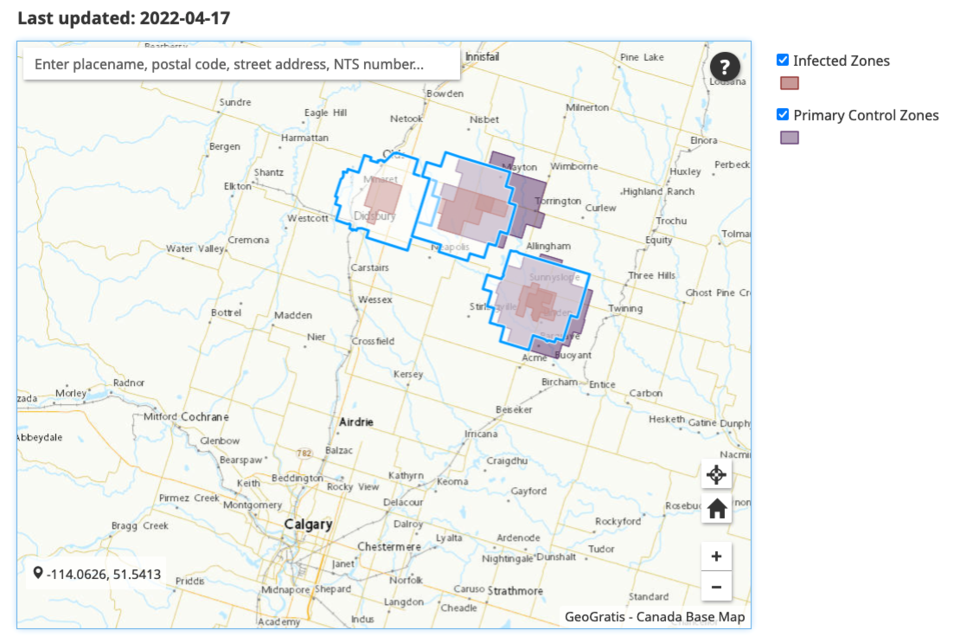

The agency says it has established Primary Control Zones (PCZ) in the areas where the disease has been identified.

“The PCZs are in place to control the risk of further spread of the virus,” reads a portion of an emailed statement from CFIA. “Each infected premises is under quarantine and will be going through a similar process which involves: destruction and disposal; compensation; cleaning and disinfection; removal of quarantine.”

Although the Albertan was unable to confirm approximately how many birds have been culled to date in the region, the agency said late last week that the infected premises in three of the zones in the region “have been depopulated and the disposal process is underway.”

The transportation of poultry as well as poultry-related products within or through the zones requires permits issued through the agency.

“Low risk movements can happen with a self-serve permit that producers and transporters can download from the CFIA website,” it says. “Higher risk movements such as live birds, carcasses, manure and hatching eggs require a specific permit.”

Pertaining to commercial poultry operations, the agency said it is working with producer marketing boards to vet and triage permits to minimize the impact on producers in the affected zones without compromising the disease control measures.

One of the zones in the region includes portions of the towns of Olds and Didsbury.

“But the general public will not normally be affected,” the agency said in response to a question about what the measures might mean for movement in the area.

“Groceries purchased at retail in either town can be brought to homes outside of the PCZ. Also, retail groceries purchased outside of the PCZ can be brought to residences inside the PCZ.”

Meanwhile, across the country, the number of animals culled had as of earlier this week nearly reached three-quarters of a million.

“Nationally, the affected premises to date have involved approximately 700,000 birds,” a spokesperson wrote by email on April 18 in response to questions, adding that a provincial level breakdown of the bird count was expected to be available on the agency's website later this week.

How long quarantines on affected properties might be expected to last depends largely on the individual situation, but can be expected to be in place for more than a month at least.

“Completion of all the steps leading to the removal of a quarantine is affected by a number of premises-specific factors,” the spokesperson said. “But the overall process typically takes about 45 days.”

Additionally, related zone and associated movement controls are not immediately lifted when an infected premise is released from quarantine, they said.

“The CFIA first completes post-outbreak surveillance to confirm that the avian influenza has been stamped out in the PCZ.”

Despite the rapid spread that has swept through avian populations, the risk of transmission to humans remains low.

“Human infections with the avian influenza virus is rare and symptoms in human cases are often limited to conjunctivitis or mild respiratory disease,” said the spokesperson.

“There is no evidence to suggest that the consumption of cooked poultry or eggs could transmit the avian flu to humans. All the evidence to date indicates that thorough cooking will kill the virus.”

Even so, the agency advises people to stay away from wild birds.

“To help prevent the spread of avian flu in bird populations and human exposure, people should avoid contact with wild birds, refrain from feeding or touching wild birds, including access to ponds or bodies of water known to be used by wild birds.”